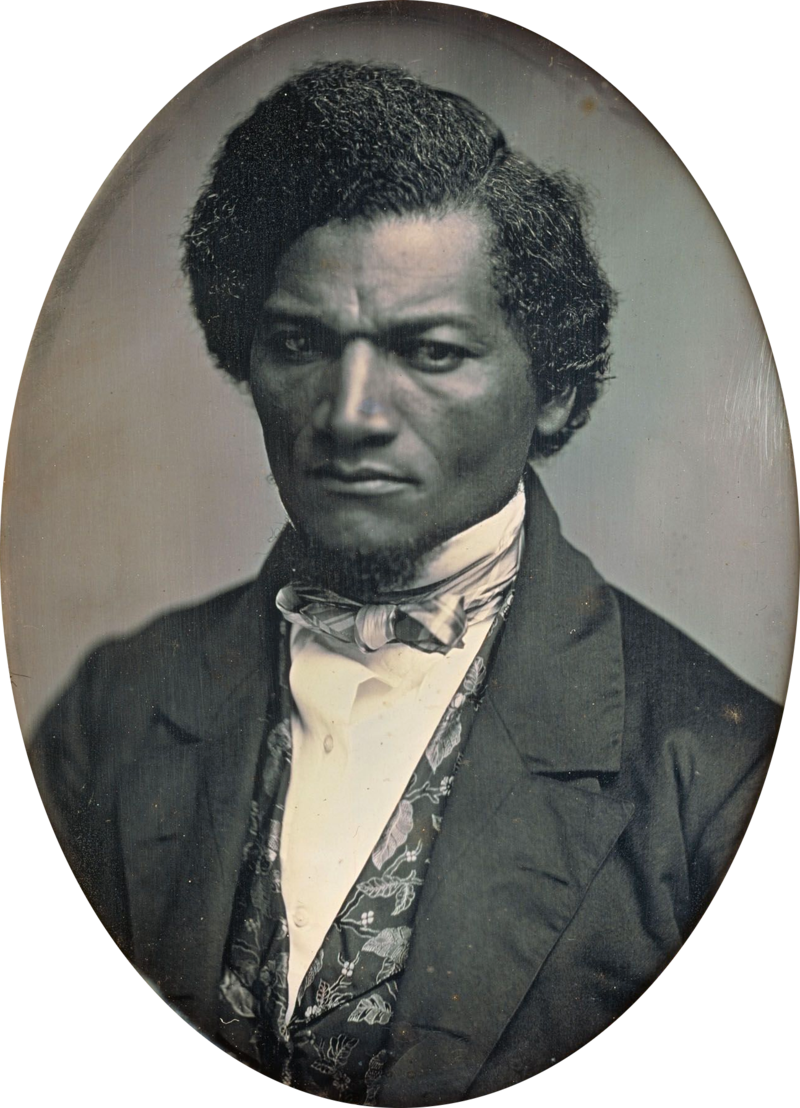

Daguerreotype photo of Frederick Douglass, ca. 1852.

The fact is, ladies and gentlemen, the distance between this platform and the slave plantation from which I escaped is considerable—and the difficulties to be overcome in getting from the latter to the former, are by no means slight. That I am here today is, to me, a matter of astonishment as well as of gratitude.

This is the 4th of July. It is the birthday of your National Independence and of your political freedom. It carries your minds back to the day and to the act of your great deliverance and to the signs and to the wonders associated with that act and that day. This celebration also marks the beginning of another year of your national life and reminds you that the Republic of America is now 76 years old. I am glad, fellow citizens, that your nation is so young. Seventy-six years, though a good old age for a man, is but a mere speck in the life of a nation.

There is hope in the thought and hope is much needed, under the dark clouds which lower above the horizon. The eye of the reformer is met with angry flashes portending disastrous times, but his heart may well beat lighter at the thought that America is young and that she is still in the impressible stage of her existence.

I have said that the Declaration of Independence is the ring bolt to the chain of your nation’s destiny; so, indeed, I regard it. The principles contained in that instrument are saving principles. Stand by those principles, be true to them on all occasions, in all places, against all foes, and at whatever cost.

Fellow-citizens pardon me, allow me to ask why am I called upon to speak here to-day? What have I or those I represent to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice embodied in that Declaration of Independence extended to us? I say it with a sad sense of the disparity between us. I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity, and independence bequeathed by your fathers is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean citizens, to mock me by asking me to speak today?

Fellow citizens; above your national, tumultuous joy, I hear the mournful wail of millions! Whose chains, heavy and grievous yesterday, are today rendered more intolerable by the jubilee shouts that reach them. My subject then, fellow citizens, is American slavery. I shall see this day and its popular characteristics from the slave’s point of view. Standing there, identified with the American bondman, making his wrongs mine, I do not hesitate to declare with all my soul that the character and conduct of this nation never looked blacker to me than on this 4th of July! Whether we turn to the declarations of the past or to the professions of the present, the conduct of the nation seems equally hideous and revolting. America is false to the past, false to the present, and solemnly binds herself to be false to the future.

I will use the severest language I can command. And yet not one word shall escape me that any man whose judgment is not blinded by prejudice or who is not at heart a slaveholder shall not confess to be right and just. But I fancy I hear some one of my audience say, it is just in this circumstance that you and your brother abolitionists fail to make a favorable impression on the public mind. Would you argue more and denounce less, would you persuade more and rebuke less, your cause would be much more likely to succeed. But I submit, where all is plain there is nothing to be argued. What point in the anti-slavery creed would you have me argue? On what branch of the subject do the people of this country need light? Must I undertake to prove that the slave is a man? That point is conceded already. Nobody doubts it. The slaveholders themselves acknowledge it in the enactment of laws for their government. They acknowledge it when they punish disobedience on the part of the slave. There are seventy-two crimes in the State of Virginia which, if committed by a black man (no matter how ignorant he be), subject him to the punishment of death while only two of the same crimes will subject a white man to the like punishment. What is this but the acknowledgement that the slave is a moral, intellectual and responsible being? The manhood of the slave is conceded. It is admitted in the fact that Southern statute books are covered with enactments forbidding under severe fines and penalties the teaching of the slave to read or to write. When you can point to any such laws in reference to the beasts of the field, then I may consent to argue the manhood of the slave.

At a time like this scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. O! Had I the ability and could I reach the nation’s ear, I would today pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire. It is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened. The conscience of the nation must be roused. The propriety of the nation must be startled. The hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.

What to the American slave is your Fourth of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him more than all other days in the year the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him your celebration is a sham. Your boasted liberty, an unholy license. Your national greatness, swelling vanity. Your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless. Your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence. Your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery. Your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings with all your religious parade and solemnity are to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices more shocking and bloody than are the people of these United States at this very hour.

The Fugitive Slave Law makes mercy to them a crime and bribes the judge who tries them. An American judge gets ten dollars for every victim he consigns to slavery and five when he fails to do so. The oath of any two villains is sufficient under this hell-black enactment to send the most pious and exemplary black man into the remorseless jaws of slavery! His own testimony is nothing. He can bring no witnesses for himself. The minister of American justice is bound by the law to hear but one side, and that side is the side of the oppressor.

You are all on fire at the mention of liberty for France or for Ireland, but are as cold as an iceberg at the thought of liberty for the enslaved of America. You discourse eloquently on the dignity of labor, yet you sustain a system which in its very essence casts a stigma upon labor. You can bare your bosom to the storm of British artillery to throw off a three-penny tax on tea, and yet wring the last hard-earned farthing from the grasp of the black laborers of your country. You profess to believe “that, of one blood, God made all nations of men to dwell on the face of all the earth” and has commanded all men everywhere to love one another. Yet you notoriously hate (and glory in your hatred), all men whose skins are not colored like your own. You declare before the world and are understood by the world to declare that you “hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal; and are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; and that, among these are, life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” And yet you hold securely, in a bondage which according to your own Thomas Jefferson, “is worse than ages of that which your fathers rose in rebellion to oppose”, a seventh part of the inhabitants of your country.

Allow me to say in conclusion, notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented of the state of the nation, I do not despair of this country. There are forces in operation which must inevitably work the downfall of slavery.

Source: BlackPast, B. (2007, January 24). (1852) Frederick Douglass, “What, To The Slave, Is The Fourth Of July”. BlackPast.org. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/speeches-african-american-history/1852-frederick-douglass-what-slave-fourth-july/

One of the most significant speeches in American history. I would argue that the issues Douglass raises here are still very relevant to how Americans perceive themselves.