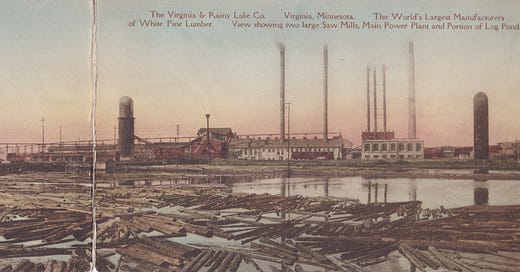

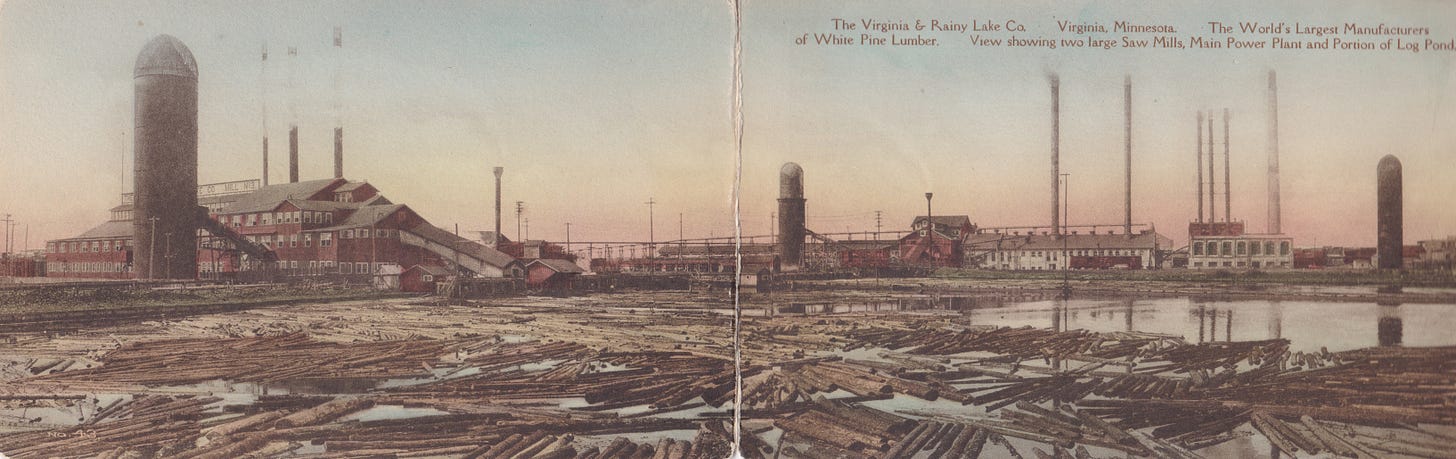

I just returned from a couple of days researching in northern Minnesota. I went to Virginia, which is right next to Eveleth in the Iron Range, but which about a hundred years ago was the location of the world’s largest white pine lumber mill (The Virginia—Rainy Lake Lumber Company). From there I shot down to Duluth, which was also a large lumber center because it was so much cheaper to ship lumber by barge on the Great Lakes than to put it on railroad cars. Duluth supplied the east coast via the lumber center at Tonawanda, near Buffalo, New York. I’ll be processing what I learned and reporting on it in much more detail, soon.

One of the things that surprised me a bit, but which makes sense once I think about it, is that the timber that became lumber in the VRL mill and the smaller W.T. Bailey mill in Virginia did not arrive by water. As I was walking around Silver Lake and Bailey (Virginia) Lake, I noticed that there isn’t a strong stream running into them. My host at the historical society museum, Tucker Nelson, verified that in the past there was a slightly larger stream running into and out of these two small lakes; but not one that was big enough to carry the masses of logs these mills processed. The lakes were used as holding ponds, but the logs came by rail from the forests to the north and were dumped from the cars into the lake. Similarly, Charlene Langowski at the St. Louis County Historical Society in Duluth mentioned that although a lot of streams fed the St. Louis River, many weren’t really large enough to float logs. I’ll have to read more about that, since my understanding up to this point has been that lumberjacks were very skilled in making use of spring “freshets” and damming streams to build enough flow to move timber. But maybe it’s a question of cost-effectiveness, once narrow-gage railroads could be built into the woods.

I was completely unaware that the Duluth museum was in the railroad depot and included a huge display of locomotives, cars, and even an extremely rare McGiffert steam-powered log loader (there are only three left). A Duluth native named J.R. McGiffert patented this device in June, 1908 and produced over a thousand at a Duluth iron works. McGifferts could load about 350,000 board feet onto rail cars daily, and they operated year-round. This was another important factor in breaking free of the seasonality that had been typical in the early decades of logging.

I’m beginning to see the outlines of a history here. There seem to be two eras of the lumber industry in the nineteenth century, separated by the Civil War. In the first, the work in the forests was seasonal and water was the most important route for both timber and lumber. In the earliest part of this first phase, water also powered mills. After the war, railroads began to take over both the distribution of lumber and the supply of timber from the woods. The industry became a steadier, year-round employer and mills became larger. This is the industrial lumber era when labor organization became important, especially after the beginning of the twentieth century. It’s also probably a period when cutover fires and decreasing supplies of timber began attracting the attention of foresters and conservationists. This is going to be a big, thick book!