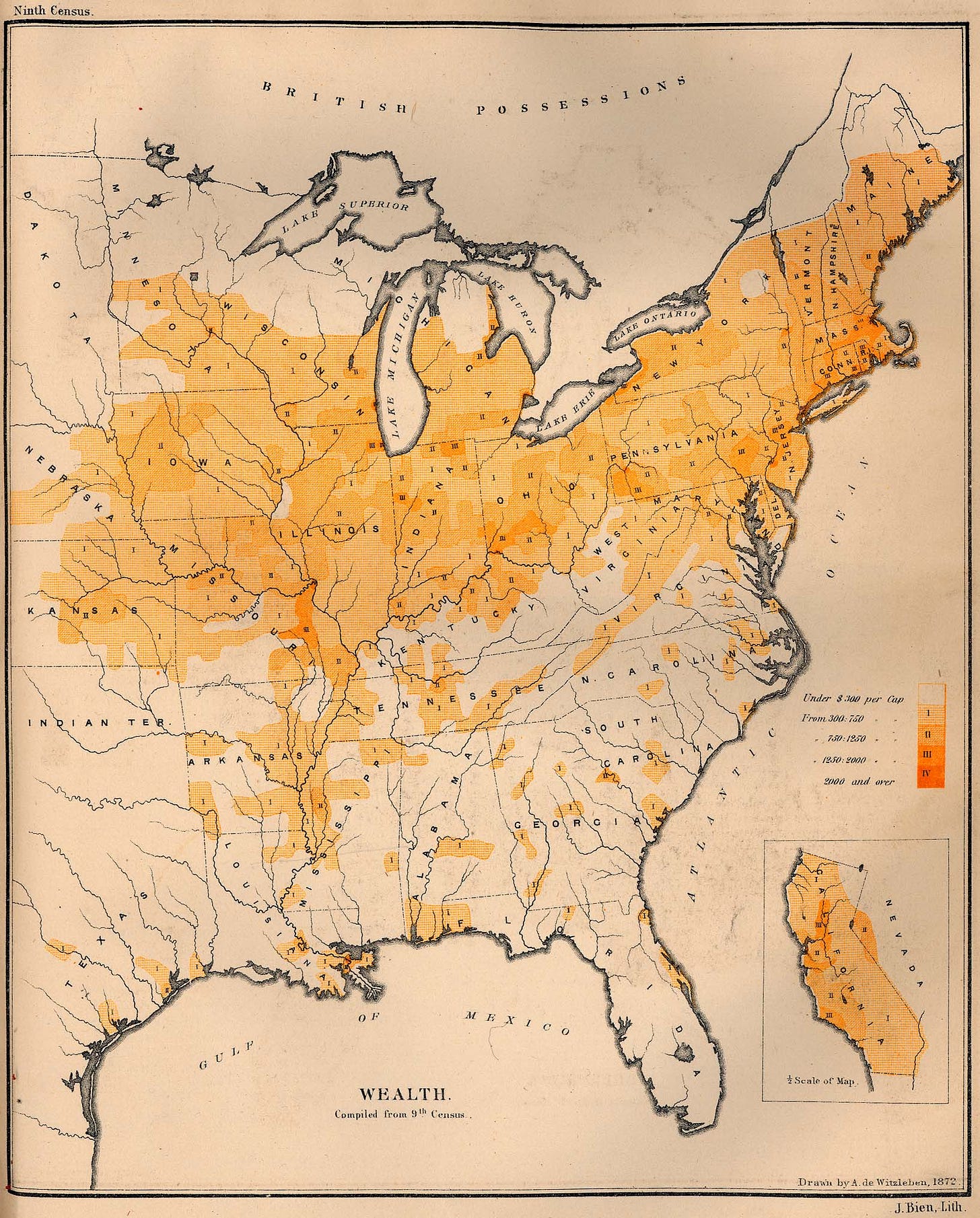

The distribution of wealth per capita in 1872, illustrating the disparity between North and South.

Lynchburg, Va., July 31, 1865.

The rough little city is built on several round-topped hills that descend abruptly to the banks of the James, which is here an insignificant stream at the bottom of a rocky valley hardly wider than the river’s bed. The streets which run towards the water are almost precipitous and all the streets, whether steep or not, are dirty and ill-paved. At present they are unlighted at night and though guarded by soldiers are considered unsafe after nightfall. The warehouses, manufactories, and private residences are for the most part mean in appearance and the stranger is surprised to learn that before the war, in proportion to the number of inhabitants, Lynchburg was with the single exception of New Bedford, Massachusetts the richest city in the United States. But if there is little which to the casual eye is indicative of wealth, there are many signs that the reputation of the place as a famous tobacco mart was well deserved.

The opinion seems to prevail among the people that the renown of their city as the tobacco metropolis has passed away with slavery and that, for a long time at least, it will not return. They say that free labor cannot be profitably applied to the culture of tobacco on a large scale.

These gentlemen firmly believe that the negro not only will be, but that in most parts of the South he today is, a pauper. Yet I find no man who does not admit that in his own particular neighborhood the negroes are doing tolerably well — are performing whatever agricultural labor is done. From the most trustworthy sources I learn that in the vicinity of Lynchburg, of Danville, of Wytheville — in counties embracing a great part of southern and southwestern Virginia — the colored population may be truly described as orderly, industrious, and self-supporting. And this seems to be plainly shown by the reports drawn up by Government officials of the issue to citizens of what are known as “Destitute Rations”. This distribution has been going on ever since the end of May but very recently the General commanding in this district has deemed it proper to stop all issues of rations to citizens, except in well authenticated instances of actual pauperism. Whatever may have been the case immediately after the occupation of this part of Virginia by the Federal troops, for some time past it has been plainly discernible that the very large majority of those claiming to be destitute might easily support life without taxing the charity of the Government.

An order made in May last by General Gregg which allows farmers, in order that they may be the better able to provide for the laborers upon their plantations, to buy supplies from the military stores, paying for them in cash or giving bonds to pay for them in cash or in kind when the crops shall have been harvested, has not I think been rescinded by General Curtis, but is still in force. In the earlier part of the season many planters availed themselves of the permission thus granted, which was doubtless of advantage to them and to the negroes. In reference to the remarkable fact that so very few negroes of all the great number inhabiting the region round about Lynchburg have sought food from the Government, it is fair to say that the military authorities, when the matter was wholly in their hands and in those of the agency of the Freedmen’s Bureau recently established, have not permitted the planters to set adrift all or any of the negroes from their homes. It is considered that the crops which in part were planted before the slaves became free and which have all been worked by them throughout the year are justly chargeable with the support of the laborers and those dependent upon them. Some planters have shown a disposition to turn loose all such negroes as were neither able bodied themselves nor had near relations able to work and whose labor could be taken as payment for the board and lodging of all. One gentleman, somewhat advanced in years and averse to the trouble of managing free negroes, wished to let his farm stand idle and to send away at once about sixty people who might, very likely, have become a burden on the community at large. He was very angry when informed that no such discharge could be permitted and that for the present at least the negroes must stay where they were. But the large majority of farmers have kept with them those of their former slaves who would stay and the large majority of these latter willingly remain in their old homes and work for wages. The amount of pay given them varies a good deal. When wages are paid in money, five dollars per month seems to be the usual rate. But it is believed that on many plantations nothing more is given than the food and clothes of the laborer and his family. Some plantations are “worked on shares”. In one case which has fallen under my observation, the employer agrees to feed and clothe the laborers, to allow each family a patch of ground for a garden, and at the end of the year to divide among them one-seventh of the total produce of the farm. The crops planted are corn, oats, wheat, potatoes, and sorghum. The wheat has been already divided.

Atlanta, Georgia, December 31, 1865.

The inducements to Northern men to come here and engage in agriculture, lumbering, and similar branches of business which, being carried on mainly by the services of the freedmen and for a foreign market, are not subject to the drawbacks above-mentioned, seem to be very great. There is apparent a willingness, often an anxiety even, to secure Northern men as lessees of plantations and large tracts of land, well improved and productive, are everywhere offered for sale at low prices. Sometimes at prices that may be called ruinously low. “These freedmen will work a heap better for a Yankee than they will for one of us,” it is frequently said. Other causes of this sacrifice of lands and rents are to be found in the belief that the free labor of the negroes cannot be made profitable and in the fact that many men who have much land have no money with which to cultivate it. But although much land may still be bought cheap, there are some signs that these causes will not continue to operate so extensively as heretofore. Often I hear it predicted that cotton is going to command a very high price for some years to come. That therefore its culture may be profitable, though the laborers should work a smaller number of acres than in old times. And occasionally some local newspaper announces that the gloomy prospects of the planters are brightening. That the negroes who after all showed so commendable a spirit of devotion, faithfulness, and obedience during the war are beginning in certain districts to make contracts and profess a willingness to receive a share of the crop as wages.

Macon, Georgia, January 12, 1866.

The negroes, I was told, are very generally entering into contracts with the planters and it is thought that almost all will have found employers before the 1st of February. All negroes who at that time shall be unemployed and not willing to make contracts, it is the intention of the Commissioner to arrest and treat as vagrants. The demand for labor is greater than the supply, and the Commissioner has frequent calls made upon him for able-bodied men to go to other States and to other parts of Georgia.

Montgomery, Alabama, January 24, 1866.

Cotton-planting was of course discussed — two of the men around the fire asserting that without slavery there can be no cotton. This provoked a Georgian to say that on a plantation where nobody worked before nor after daylight he could raise more bales of cotton than on a plantation where the other plan was followed. And as to white men not being able to work in the field, that was all a mistake. They could work; he’d seen white men working cotton in Texas and was mighty nigh being run out of his own town for saying so and for telling them that the doom of slavery was written by them Germans. It wouldn’t be long before you’d see white men raisin’ cotton in every State in the Confederacy. Not our white men ain’t goin’ to work, said the former speaker.

Source: Edwin Lawrence Godkin, The Nation (1865, 1866), I, 209-210; II, 110-173. https://archive.org/details/americanhistoryt00ivunse/page/448/mode/2up