The Great Conversation

The ten chapters of this short (131 page) first volume of the Great Books of the Western World describe the conversation and its importance. I thought it would be useful to begin with a synopsis of the elements I thought were key, since its point seems to be very much like mine in beginning Lifelong Learners.

In the first chapter, titled "The Tradition of the West", Robert Hutchins said the Great Conversation is so central that the West could be called "the Civilization of the Dialogue". The Great Books have been central to this dialogue and have been understood until recently (he was writing in 1951) to be indispensable to educating people "to lead human lives". Liberal education should be understood in the old sense of liberal: pertaining to liberty. This means it is neither vocational training nor purely theoretical speculation, but is designed "to clarify the basic problems and understand the way one problem bears upon another", and to "grasp the methods by which solutions can be reached and the formulation of standards for testing solutions proposed." (3)

In the next chapter, "Modern Times", Hutchins said that in modern America, "people now have political power and leisure". (8) But the entertainments people tend to choose are like narcotics that degrade their ability to think, which is dangerous for citizens in a democracy. Hutchins quoted from John Dewey's 1916 book, Democracy and Education, agreeing that there is a connection between the work people do and their education but objecting that the purpose of education is not to prepare people for jobs (as he said Dewey's followers concluded by mistake). He said modern Americans were "so wrapped up in our own occupations and the special interests of our own occupational groups" that no one was able to consider the common good. And he concluded that, writing before the industrial assembly line became prevalent, Dewey failed to recognize "the humanization of work is one of the most baffling issues of our time." This humanization of work, he said, must come "through understanding" provided by the humanities.

The next chapter, "Education and Economics", returned to the theme of making a liberal education available to everybody. In the past, the humanities had been reserved for elite students. But "uneducated political power is dangerous" and the "uneducated leisure" available to increasing numbers of Americans leads to problems. "If the people are incapable", Hutchins said (and I would add, or are unwilling) "of achieving the education that responsible democratic citizenship demands, then democracy is doomed." (18) Lack of education, he warned, "has led to the development of all kinds of cults...and to the extension on an unprecedented scale of the most trivial recreations." (22) Hutchins quoted Adam Smith’s description of "the torpor" that resulted when division of labor resulted in people doing meaningless, mindless tasks. If this led to the dumbing down of citizens, then "industrialization and democracy are fundamentally opposed." (23) Luckily, "That mechanization which tends to reduce man to a robot also supplies the economic base and the leisure that will enable him to get a liberal education and to become truly a man." (I'll just say, this once, that when Hutchins says "man" I am giving him the benefit of the doubt and chalking it up to an archaic usage of the term, that covers both sexes.)

The two chapters that follow cover "The Disappearance of Liberal Education" and "Experimental Science". Hutchins said that although the West was "committed to universal, free, compulsory education", it "has not accepted the proposition that the democratic ideal demands liberal education for all". (24) Unfortunately, the forms of education had failed to follow the function and too often, "the curriculum is extra and the extra-curriculum is the heart of the matter". (25) Entrance examinations created "tariff walls" to the academy, "depriving the rising generation of an important part of their cultural heritage" and the tools they needed to become responsible citizens. Further, by creating narrow academic disciplines and faddishly following new technologies, the educational system made important truths harder rather than easier for students to comprehend. In consequence, "As is common in educational discussion, the public had confused names and things" and had assumed that in light of all the new, modern specializations, the Great Conversation had become irrelevant. (29) The irony was that:

The effectiveness of modern methods of communication in promoting a community depends on whether there is something intelligible and human to communicate. This, in turn, depends on a common language, a common stock of ideas, and common human standards. These the Great Conversation affords...We could talk to one another then.

This conversation required more than literature, Hutchins said. It required a basic understanding of the sciences and the scientific methods that provide the foundations of technological progress. And the sciences needed "stimulation from philosophy and the arts and literature" to provide context and direction for their research.

Chapter six was called "Education for All". Hutchins began by addressing the criticism that a liberal education was an elite education; that "The ideal that you propose was put forward by and for aristocrats". (43) He answered that this was once true, when aristocrats were the only people who needed to make political decisions. In a democracy everyone needs the type of education that makes them effective citizens. I would add that the criticism also rightly implies that the content of this education was created by the aristocracy, for the aristocracy. While this is often true and a lot of the Great Conversation may have been a clubby exchange between rich white men, I don't think the appropriate response is to cancel and ignore it.

Hutchins said in response to these imagined critics, that "they believe that the great mass of mankind is and of right ought to be condemned to a modern version of natural slavery." (44) He asked, "Is there so little education in the American education system because that system is democratic? Are democracy and education incompatible? Do we have to say that, if everybody is to go to school, the necessary consequence is that nobody will be educated?" These were rhetorical questions, but they seem to underline the problem that "There appears to be an innate human tendency to underrate the capacity of those who do not belong in 'our' group." (45) Hutchins was unsympathetic to the objections of students who didn't think they wanted to study these texts. "The art of teaching," he said, "consists in large part of interesting people in things that ought to interest them, but do not." (49) The goal of this education was "comprehension of the tradition in which we live and our ability to communicate with others who live in the same tradition." (50)

In the next chapter, Hutchins focused on "The Education of Adults." In modern America, this

has uniformly been designed either to make up for the deficiencies of their schooling, in which case it might terminate when those gaps had been filled, or it has consisted of vocational training, in which case it might terminate when training adequate to the post in question has been gained. What is here proposed is interminable liberal education.

He argued that a person should not and "cannot expect to store up an education in childhood that will last all his life." (52) The leisure created by modern living, Hutchins said, "seems destined...to end in the trivialization of life. It is impossible to believe that men can long be satisfied with the kind of recreations that now occupy the bulk of their free time." (53) But this is more than just a petty problem. "If independent judgment is the sine qua non of effective citizenship in a democracy, then it must be admitted that such judgment is harder to maintain now than it has ever been before." In order to develop and maintain this skill, "constant mental alertness and mental growth are required." And unfortunately, "most of the important things that human beings ought to understand cannot be comprehended in youth." (54) Adult experience and reflection are needed to really appreciate the insights contained in the Great Books, so it does little good cramming them during childhood and believing the job is done. And ironically, "liberal education can flourish in the schools, colleges, and universities of a country only if the adult population understands and values it." Hutchins hoped that the Great Books series would help "the adult population of laymen...to regard these issues as important." Once that happened, "It would become respectable for intelligent young people, young people with ideas, to devote their lives to the study of these issues." (56)

The eighth chapter, "The Next Great Change", deals with the new global reality of the post-war decade. Humanity's new ability to destroy life on earth (after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the USSR detonated their first nuclear device in 1949 and the US had the hydrogen bomb by 1952) made "world cooperation and community" an urgent issue, and Hutchins knew "time is of the essence." (58) The problem was that the United States was still a young nation, "Nor has it had the kind of education, in the last fifty years, that is conducive to understanding its position or to maintaining it with balance, dignity, and charity." (59) As an example of this problem, Hutchins said "some of our most representative citizens constantly demand the suppression of free speech in the interest of national security." (61) This was true: the McCarthy era was just getting under way, and a generation earlier the the American government had jailed dissenters for sedition during the Great War. The perpetrator of this injustice was a former university president, so perhaps it makes sense that Hutchins announced "it is time to take education away from the scholars and school teachers and to open the gates of the republic of learning to those who can and will make it responsible to humanity." (64) He concluded, "Political freedom cannot last without provision for the free unlimited acquisition of knowledge. Truth is not long retained in human affairs without continual learning and relearning. A political order is tyrannical if it is not rational." (65)

Next Hutchins addressed the tensions of the Cold War in a chapter called "East and West". He began by admitting that the Great Conversation he was promoting was based on the Great Books of the Western World. The series does not include any of the classics of Eastern philosophy or literature. However, this was not because the editors of the series did not believe there were any worthy candidates. Hutchins acknowledged that "there is undoubtedly to be a meeting of East and West." (66) In fact, he said, there were many deep elements of Western wisdom that were echoed in writings from Asia and that a lasting peace with Asian cultures would ultimately have to be based on understanding and respect for their traditions, and not on hopes of "modernizing" their societies to conform with Western ideas. "But at the moment," he concluded, "we have all we can do to understand ourselves in order to be prepared for the forthcoming meetings." (73)

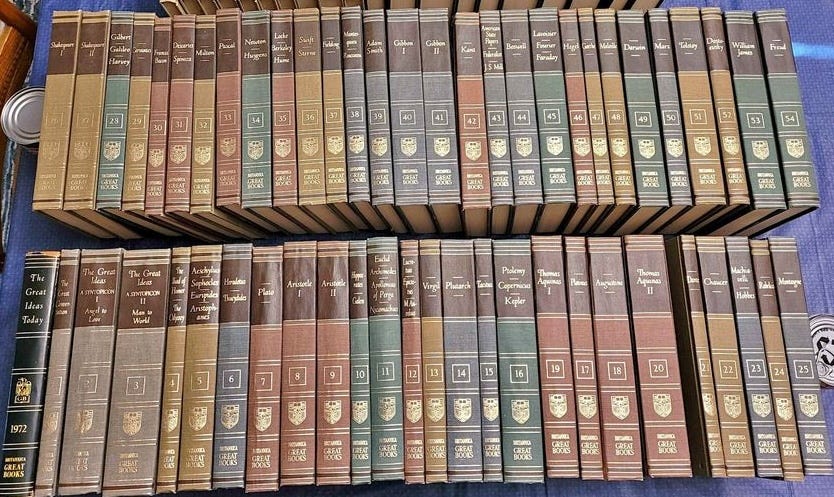

The final chapter was called "A Letter to the Reader". Hutchins put his case for the Great Books in definite terms: "We say that these books contain a liberal education and that everybody ought to try to get one." (74) What makes them great, he said, "is, among other things, that they teach you something every time you read them." Most high school and college students read only a few of these; Hutchins admitted that in his own college career he had read only some Shakespeare and Goethe's Faust. But even if someone had somehow managed to read them all, he said, "every man's mind ought to keep working all his life long...every man ought to push toward the horizons of his intellectual powers all the time." (75-6) He reiterated his argument that "The great issues, now issues of life and death for civilization, call for mature minds." And also, the minds of regular people. "We have built around the 'classics'," he said, "such an air of pedantry, we have left them so long to the scholarly dissectors." (77) But most of them were written for regular, educated people to read. It is easier, he said, to read them in chronological order, since the authors of later books were "in conversation" with what had come before. But wherever one begins, the most important thing is becoming part of the conversation.

The alternative, Hutchins said, is "that we can leave all intellectual activity, and all political responsibility, to somebody else and live our lives as vegetable beneficiaries of the moral and intellectual virtue of other men." Unfortunately, he continued, "the death of democracy is not likely to be an assassination from ambush. It will be a slow extinction from apathy, indifference, and undernourishment." (80) The only way out of this slow extinction, he believed, was to renew the Great Conversation. So they created the Great Books. "Anything less than the effort to help everybody get the best education necessarily implies that some cannot achieve in their own measure our human ideal." Hutchins was not ready to concede that anti-democratic implication. "The aim of education is wisdom," he concluded, "and each must have the chance to become as wise as he can.