Syntopical Construction

Originally posted 1/1/2024 on LL

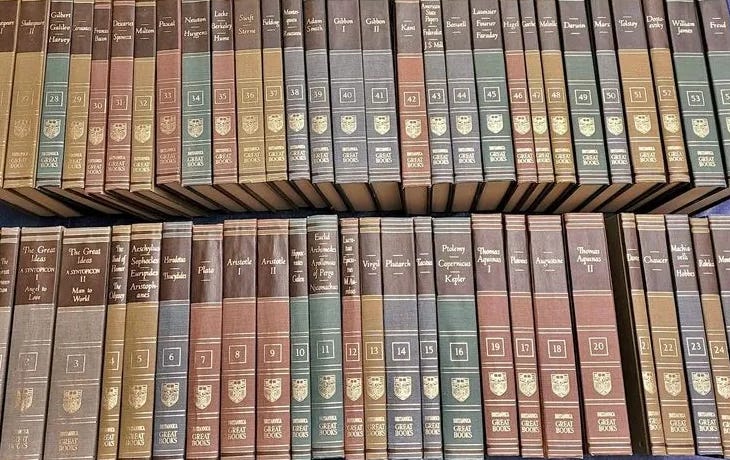

Mortimer J. Adler, "The Principles and Methods of Syntopical Construction", Appendix II, The Great Ideas, Volume II, 1219-1299.

This is the much longer, more intricate description of how the Syntopicon was written, promised in the introductory essay in Volume I. Despite the negative views of Adler and his project that became chronic after post-modernism took over the academy, I was pleased to see quite a bit of modesty and self-awareness in the ways Adler described the Syntopicon and the Great Books. For example, as he began to describe the Great Ideas, Adler emphasized that they were a selection and acknowledged that it is completely legitimate to question the "criteria controlling the selection". Adler admitted the possibility of disagreement, but suggests that well-meaning people had done their best. Having set aside the question of the Great Books being the final authority on the canon, he did affirm that the theme of both the Great Books and the Great Ideas was "the unity and continuity of the tradition of western thought". This is interesting, especially if contrasted with historians' focus on change over time, which would tend to highlight differences more than similarities. Adler returned to this idea later in the essay.

The 102 Great Ideas were whittled down from a much larger list over two years by eliminating "those which did not appear to receive extensive or elaborate treatment in the Great Books". This is interesting, because it reminds us that these ideas were not the committee's choices regarding what was important in western thought, but were the things western authors had focused on (and their readers had read) over nearly three millennia. It also suggests a back-and-forth process of discovering the important ideas that Adler admitted was a bit "circular" but argued that this was an indication that "the greatness of the books and the greatness of the ideas derive from the same source."

But even so, Adler was aware that the European tradition was only one of several world traditions and that an attempt to find the foundational books of a global culture (which he seemed to believe the world was headed toward) would have produced a different list of Great Ideas. He also explained that the prominence of certain ideas was not uniform and was often greater at one time than at another (Angels and Evolution, for example). And the ideas themselves, even when generalized, reflect the frequency and complexity of the ways they were discussed in the 433 books and the Bible, so the list is contingent rather than determined by an interpretation or ideology. Some ideas, like Society, would not have been mentioned in early texts using that term; another challenge for the researchers.

Great Ideas had varying numbers of links (we saw that when looking at the Syntopicon Graph) and some sub-ideas had nearly as many links as some of the Great Ideas. These could be considered as "runners-up" in the process of selecting the 102 Great Ideas. Adler also discussed the variations in linkages creating "constellations" of Great Ideas and their sub-ideas that were analogous to intellectual disciplines (political thought, religious thought, etc.), where the ideas within them shared more links than they did with other ideas in different disciplines. This was also evident in the Obsidian Graph I made, although it was interesting to note that there was typically only one or two degrees of separation between any of the ideas in the set.

Adler discussed in detail the choices he had made in constructing the Outlines, Introduction, and Reference sections of each chapter. He admitted that the Outlines were flawed, but suggested this was necessary, because they reflected the Great Conversation as it played out over western history rather than an ideal discussion of the ideas. So in a sense, they're historical Outlines rather than logical. But as far as history goes, the ideas were treated more as if the authors were all contemporaries engaged in a conversation, despite being presented chronologically. Adler did seem to realize, however, that the authors existed within their own times and places. This must have required extreme care in making sure the terminologies lined up correctly.

I thought a very revealing moment was when Adler said, "By taking the point of view of future world history, we can imagine how the whole tradition of western culture may some day appear as a single parochial episode". This suggested to me both that Adler was sensitive to the world literature that was not yet included, and to his imagination (hope?) of a future world culture. In another moment of modesty, Adler said the ideas presented in the Great Books were there, but that didn't make them true. The Great Ideas tried to discuss issues with "dialectical objectivity", reporting what had been said without choosing sides. He said, "agreement and disagreement raise no more than a presumption of truth and falsity, a presumption which further inquiry can always challenge or rebut." That's a valuable lesson for today.

Decisions on what to include in the Great Ideas was based on "relevance, coherence, and sufficiency". But in the end, the ideas were presented for the reader's evaluation. In a final display of modesty, Adler said:

If a dialectical balance has been preserved, the reader should be left with the major questions to answer for himself. He should be left with the major issues unresolved, unless he has resolved them in his own mind. If he has any opinion as to where the truth lies, it should be his own, formed by him in the light of his reading, not pre-formed for him in any way. From the Introductions themselves, he should derive three types of opinion: (1) that, for each of the great ideas, these are some of the questions or issues worth considering; (2) that, for each of the questions or issues mentioned, these are some of the answers or solutions; and (3) that some of the questions are so connected that answering one of them in a certain way partly determines how others must be answered.

I was pleased with the approach Adler described in this essay, especially after reading a rather depressing take-down of the Great Books enterprise by Alex Beam. The gist of it was that the whole thing, especially the Syntopicon, was just a cynical money grab. I'll probably review it soon, because it did include some interesting historical context and fascinating details of the making of the Great Books, despite its mean-spiritedness.