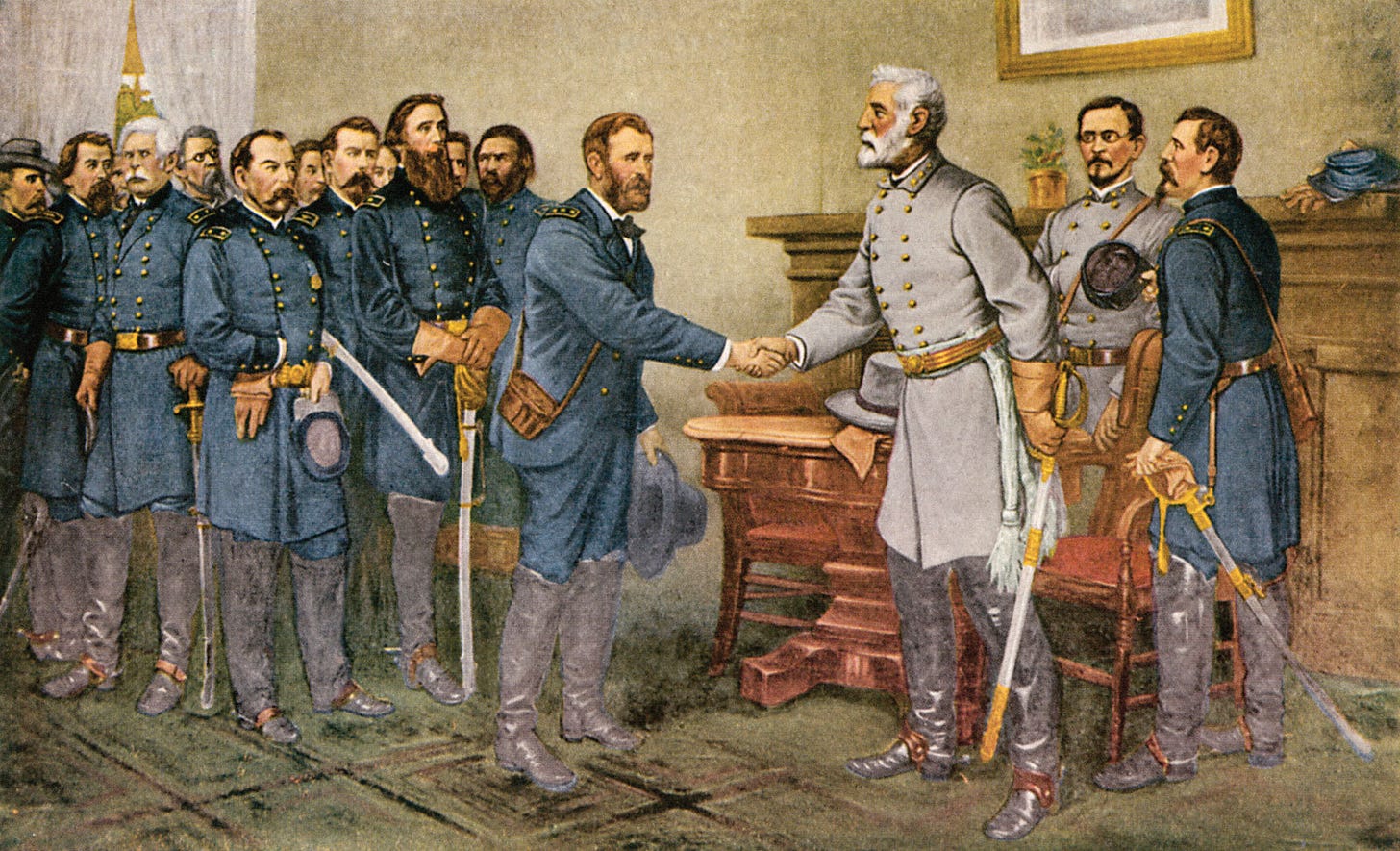

The surrender of General Lee to General Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, 9 April 1865.

On the 8th [April, 1865] I had followed the Army of the Potomac in rear of Lee. During the night I received Lee’s answer to my letter of the 8th, inviting an interview between the lines on the following morning. But it was for a different purpose from that of surrendering his army, and I answered him as follows:

[April 9.] Your note of yesterday is received. As I have no authority to treat on the subject of peace, the meeting proposed for ten A.M. today could lead to no good. I will state however, General, that I am equally anxious for peace with yourself and the whole North entertains the same feeling. The terms upon which peace can be had are well understood. By the South laying down their arms they will hasten that most desirable event, save thousands of human lives, and hundreds of millions of property not yet destroyed. Sincerely hoping that all our difficulties may be settled without the loss of another life, I subscribe myself, etc.

Lee sent this message to me:

[April 9.] I received your note of this morning on the picket-line whither I had come to meet you and ascertain definitely what terms were embraced in your proposal of yesterday with reference to the surrender of this army. I now request an interview in accordance with the offer contained in your letter of yesterday for that purpose.

I found him at the house of a Mr. McLean at Appomattox Court House with Colonel Marshall, one of his staff officers, awaiting my arrival. We greeted each other and after shaking hands took our seats. I had my staff with me, a good portion of whom were in the room during the whole of the interview.

What General Lee’s feelings were I do not know. As he was a man of much dignity with an impassible face, it was impossible to say whether he felt inwardly glad that the end had finally come or felt sad over the result and was too manly to show it. Whatever his feelings, they were entirely concealed from my observation. But my own feelings, which had been quite jubilant on the receipt of his letter, were sad and depressed. I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was I believe one of the worst for which a people ever fought and one for which there was the least excuse. I do not question however, the sincerity of the great mass of those who were opposed to us.

General Lee was dressed in a full uniform which was entirely new and was wearing a sword of considerable value, very likely the sword which had been presented by the State of Virginia. At all events, it was an entirely different sword from the one that would ordinarily be worn in the field. In my rough traveling suit, the uniform of a private with the straps of a lieutenant-general, I must have contrasted very strangely with a man so handsomely dressed, six feet high and of faultless form. But this was not a matter that I thought of until afterwards.

We soon fell into a conversation about old army times. He remarked that he remembered me very well in the old army and I told him that as a matter of course I remembered him perfectly, but from the difference in our rank and years (there being about sixteen years’ difference in our ages) I had thought it very likely that I had not attracted his attention sufficiently to be remembered by him after such a long interval. Our conversation grew so pleasant that I almost forgot the object of our meeting. After the conversation had run on in this style for some time, General Lee called my attention to the object of our meeting and said that he had asked for this interview for the purpose of getting from me the terms I proposed to give his army. I said that I meant merely that his army should lay down their arms, not to take them up again during the continuance of the war unless duly and properly exchanged. He said that he had so understood my letter.

Then we gradually fell off again into conversation about matters foreign to the subject which had brought us together. This continued for some little time, when General Lee again interrupted the course of the conversation by suggesting that the terms I proposed to give his army ought to be written out. I called to General Parker, secretary on my staff, for writing materials, and commenced writing out the following:

[April 9.] In accordance with the substance of my letter to you of the 8th inst. [of this month], I propose to receive the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia on the following terms, to wit: Rolls of all the officers and men to be made in duplicate. One copy to be given to an officer designated by me, the other to be retained by such officer or officers as you may designate. The officers to give their individual paroles not to take up arms against the Government of the United States until properly exchanged, and each company or regimental commander sign a like parole for the men of their commands. The arms, artillery, and public property to be parked and stacked, and turned over to the officer appointed by me to receive them. This will not embrace the side-arms of the officers, nor their private horses or baggage. This done, each officer and man will be allowed to return to their homes, not to be disturbed by United States authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside.

When I put my pen to the paper I did not know the first word that I should make use of in writing the terms. I only knew what was in my mind and I wished to express it clearly, so that there could be no mistaking it. As I wrote on, the thought occurred to me that the officers had their own private horses and effects which were important to them but of no value to us; also that it would be an unnecessary humiliation to call upon them to deliver their side arms.

No conversation, not one word, passed between General Lee and myself either about private property, side arms, or kindred subjects. He appeared to have no objections to the terms first proposed, or if he had a point to make against them he wished to wait until they were in writing to make it. When he read over that part of the terms about side arms, horses, and private property of the officers, he remarked with some feeling I thought, that this would have a happy effect upon his army.

Then after a little further conversation, General Lee remarked to me again that their army was organized a little differently from the army of the United States (still maintaining by implication that we were two countries); that in their army the cavalrymen and artillerists owned their own horses. And he asked if he was to understand that the men who so owned their horses were to be permitted to retain them. I told him that as the terms were written they would not; that only the officers were permitted to take their private property. He then, after reading over the terms a second time, remarked that that was clear.

I then said to him that I thought this would be about the last battle of the war. I sincerely hoped so and I said further I took it that most of the men in the ranks were small farmers. The whole country had been so raided by the two armies that it was doubtful whether they would be able to put in a crop to carry themselves and their families through the next winter without the aid of the horses they were then riding. The United States did not want them and I would therefore instruct the officers I left behind to receive the paroles of his troops to let every man of the Confederate army who claimed to own a horse or mule take the animal to his home. Lee remarked again that this would have a happy effect.

When news of the surrender first reached our lines our men commenced firing a salute of a hundred guns in honor of the victory. I at once sent word however, to have it stopped. The Confederates were now our prisoners and we did not want to exult over their downfall.

Source: Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs (1886), II, 483-496. https://archive.org/details/americanhistoryt00ivunse/page/436/mode/2up

And at that moment the Republic of the Fathers was gone forever.