Some Thoughts on Robert Owen

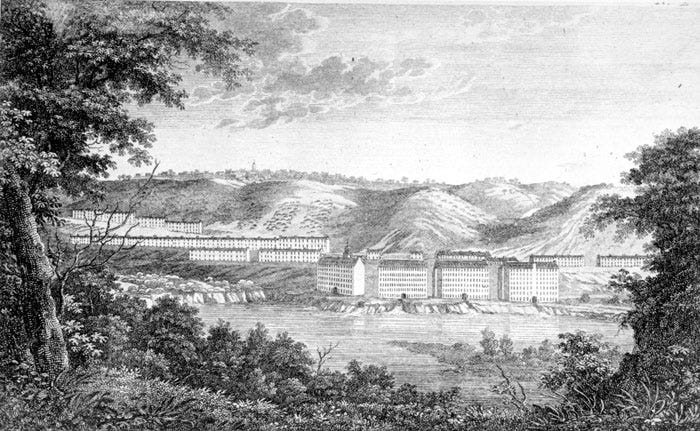

One of the specific events that accelerated the industrial revolution in America was a visit to Scotland in 1810 and 1811 by a pair of prosperous Boston merchants named Nathan Appleton and Francis Cabot Lowell, who toured the textile mills at New Lanark. These woolen mills on the River Clyde southeast of Glasgow were run by an innovative industrialist named Robert Owen, and were the largest completely water-powered mills in Great Britain. Owen’s textile operation employed so many people that the company had built an entire community around the factories to house the mill-workers and their families.

Robert Owen and his partners had bought the mills in 1799 from David Dale, Owen’s father-in-law. Sensitive to the negative social changes that industrial growth had brought to other parts of Britain, Owen established schools for the children of his workers and social organizations for the families. He put an end to the long-standing custom of forcing workers to buy only from the company store and tried to make New Lanark a real, living town. Owen’s partners objected to his philanthropy, claiming that healthy, happy, well-educated workers did not really boost the bottom line. Rather than fight with them, Owen simply bought his partners out.

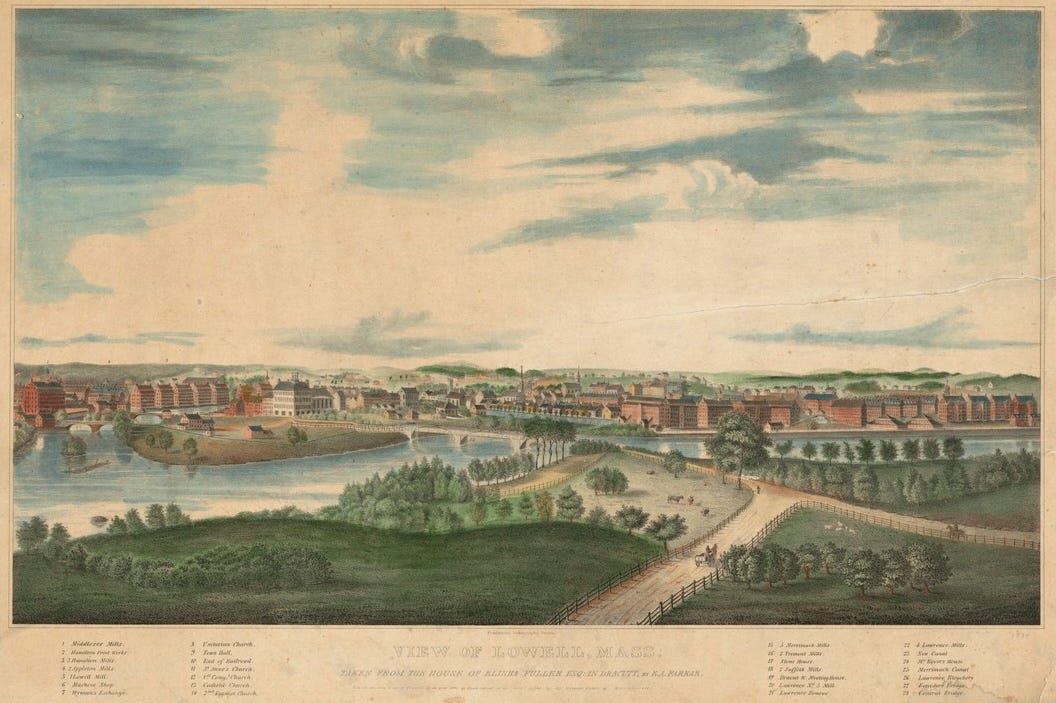

Appleton and Lowell returned to America and immediately began the Boston Manufacturing Company (BMC) in 1813 on the Charles River in Waltham, Massachusetts. At that time there were already twenty-three other mills on the Charles, but the BMC was something different. Appleton and Lowell’s mill was a completely water-powered textile factory on the model of New Lanark. The Boston Associates also followed Owen’s example in social engineering, and began building complete industrial cities in New England. Nashua, Manchester, and Concord on the Merrimack River grew from small agricultural towns to large textile cities. Lawrence and Lowell were built from the ground up as factory cities. Young people throughout the region, especially the daughters of farm families, flocked to these new industrial centers for the relative independence of factory employment. BMC mills employed mostly young women, aged 15 to 30. Between 1840 and 1860, the number of mill girls working in the Massachusetts textile industry rose from about ten thousand to over a hundred thousand. For context, the population of New England’s largest city, Boston, was about 93,000 in 1840 and still only 178,000 in 1860. By 1848, Lowell was the largest industrial city in America.

When the BMC opened their first mill, only seven out of a hundred Americans lived in cities. By the middle of the nineteenth century, the nation’s urban population was approaching twenty percent. A hundred thousand young women moved to the city to work twelve hours a day in the textile mills. In spite of harsh work conditions and low pay, many of these women were experiencing personal freedom for the first time, and liking it. Most never went back to the countryside. As cities like Lowell, Lawrence, and Manchester grew around the mills, they created a new American population group, the urban wage-worker. The mill girls and other factory workers lived a different life and had very different concerns from those of the families they’d left behind in the countryside. Although they joined the new labor movement, formed America’s first union, and were often critical of the mills they worked in, the mill girls’ lives became tied to the wellbeing of the industry that employed them.

The development of the New England textile industry illustrates how subtle, often unnoticed changes in laws and customs accumulated over time to create the world of global corporatism we live in today. Changes begun in the New England textile industry lead directly to the ways we understand corporations, shared resources, and social responsibility today. I’ve discussed that in another post. Let’s return to the beginning of this story, to Robert Owen.

Robert Owen organized a modern industrial community from the ground up in New Lanark. Appleton and Lowell learned from Owen that social engineering on a grand scale was possible, and they returned to New England inspired and followed Owen’s example in Waltham and then along the Merrimack River. What did Owen do after meeting Appleton and Lowell? Owen became the father of the British cooperative movement. In addition to being a wildly successful entrepreneur and capitalist, Robert Owen promoted a system of corporate welfare that his critics, then and now, called socialist. Owen, however, embraced the term.

Robert Owen tried to improve the society his father-in-law had created around the textile factories, by building schools and by taking care of the health and welfare of his workers. New Lanark became a model of humane industrialism and socially responsible urban planning. But that wasn’t enough for Owen. After his success in Scotland, Owen wondered how much farther he could go. So he sold his interest in New Lanark and moved to Indiana, where he founded a cooperative community called New Harmony. Like Appleton and Lowell, Robert Owen seems to have experienced an “Aha!” moment when he realized how much power he held to change society and perhaps even to change people. But unlike the Boston Associates, who built a textile empire that made them millionaires, Owen chose to do something different with that power. Robert Owen’s decision suggests that despite what often seems like inevitability, history often comes down to a series of human choices.