Packers Before (and After) Chicago

Historiography

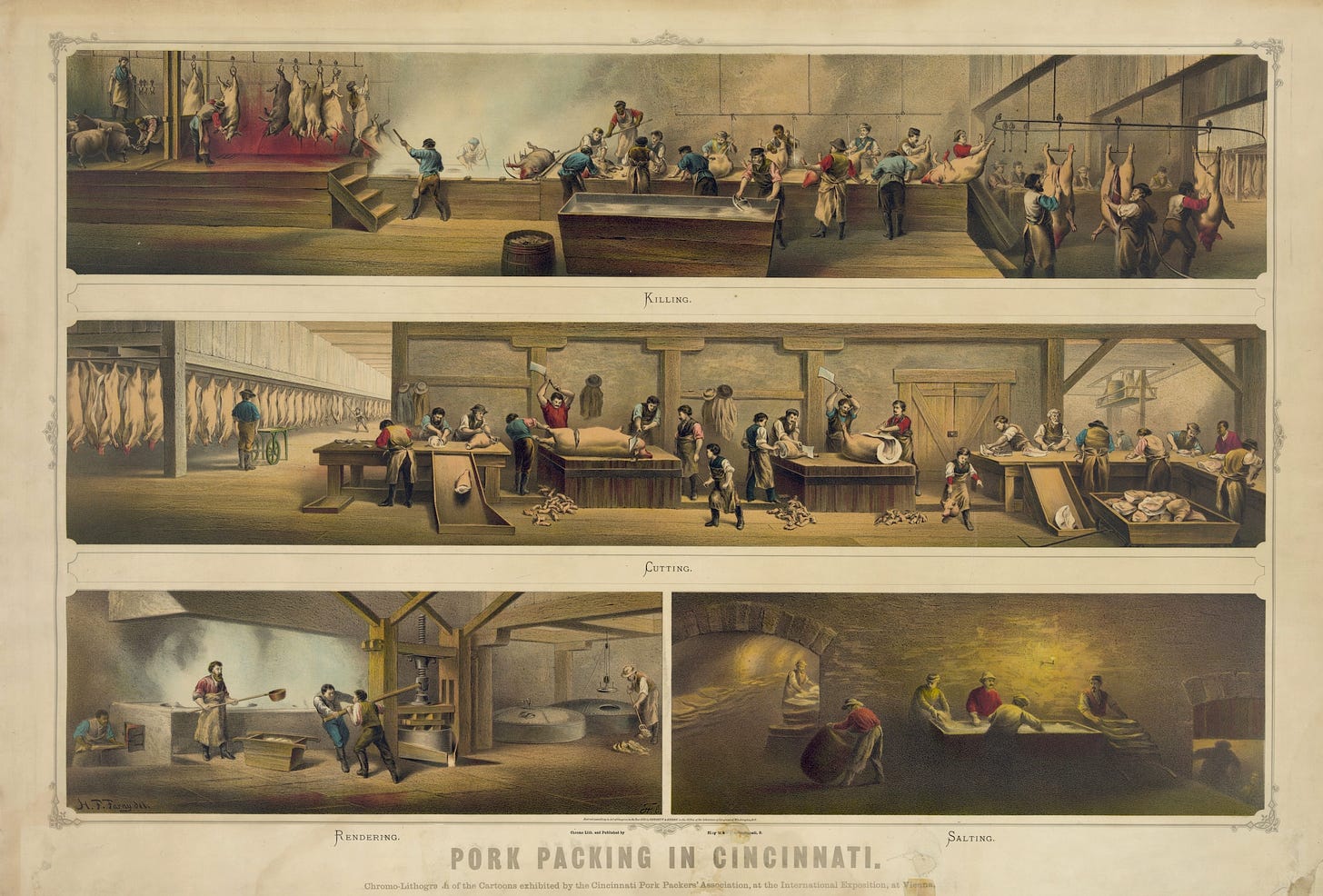

The Rise of the Midwestern Meat Packing Industry

Margaret Walsh, 1982

Margaret Walsh followed up on her 1972 book, The Manufacturing Frontier, with a look at the transition (between 1840-1870 more or less) of pork processing from a local, seasonal activity to an industry. She explained, “pork packing is a good tool of analysis because agricultural processing early disseminated an industrial experience to newly settled farming country.” But also, it seems obvious, because primary processing is industry. By 1870, Walsh said, the midwest was already “responsible for 27 percent of the nation’s value added.” William Cronon notwithstanding, a lot of that took place outside Chicago.

Early meatpackers were usually merchants in towns like Chillicothe, Hamilton, Circleville, Ripley, and Maysville Ohio, Terre Haute and Lafayette Indiana. Although she did not elaborate much on the farmers raising these swine, Walsh said that by the 1840s they had moved past semi-wild “razorbacks” that had descended from escaped colonial swine (pigs are not native to the Americas) to “foreign pigs, such as the Suffolk, Berkshire, Yorkshire, Irish Grazier, Poland, Essex, Chinese, and Chester Whites. They debated the merits of the different breeds [and knew] the defects of particular strains could be countered by crossbreeding, a practice that most farmers quickly advocated.” A closer look at the supply side of pork packing would help explain what was happening on farms during this period. Walsh showed farmers were making business decisions about the market by the 1840s, calculating “the value of corn when sold in the form of pork” to determine whether to fatten hogs or sell their grain. This calculation required knowledge of feeding yields and prices, but also of transportation costs and risks; and it involved guesswork about demand in faraway markets. So, farmers needed to be aware of the wider world even before the railroads came to town.

The operational costs Walsh reported (or estimated) for even a medium scale packing operation were substantial. Fixed costs were low (especially relative to “machinery plants or textile factories”) but the cost of the hogs meant that a “country pork merchant in the Middle Ohio Valley in the mid-1840s might need $45,000 to process 6,000 hogs.” The “city capitalist in Cincinnati, Louisville, or Madison might process 15,000 hogs [and] needed between $100,000 and $125,000 to carry out his season’s work in the mid-1840s.” This scale suggests two things. City packers had the backing of capitalists (Walsh traced several of these formal and informal relationships) and rural packers had extensive networks of trust and credit. Assuming the average general store owner could not raise the specie to do a cash business, his ability to pack hogs testified to extremely solid relationships between farmers, packers, and possibly retailers in remote cities.

Some early rural pork found its way into international markets. Walsh said “in the 1830s the United States replaced Ireland as the world’s leading source of cheap provisions.” By the 1840s “bacon and ham exports alone reached 166 million pounds.” Shipments of processed pork were made easier by the growth of the rail network. But the same trains that carried barrels could carry live animals and the railroads led to gradual consolidation of the industry to higher volume centers. Even with the growth of regional packing in Madison IN (63,000 hogs in 1845-6), Louisville KY (67,000), and Cincinnati (246,000), smaller packing centers like Burlington IA (24,000 hogs per year in the late 1850s), Muscatine IA (28,000), Keokuk IA (35,000) and Terre Haute IN (47,000) remained strong suppliers. “In the mid-1840s the Queen City’s [Cincinnati’s] annual output of 230,000 hogs produced 22 percent of the region’s total pack.” Even by the late 1850s, the four major centers (Cincinnati, Lousville, Chicago and St. Louis) accounted for less than 40 percent of the region’s pack. Pork remained an important local business after the Civil War, if the experience of what Walsh called “secondary midwestern points” is any indication. Between 1858 and 1877, many of these saw level or increasing production, with Des Moines and Cedar Rapids growing from zero to a combined total of over 200,000 hogs.

Part of this regional growth was the result of packers leaving centers like Chicago in the 1870s. They brought capital and technology to smaller cities like Cedar Rapids and Ottumwa (Thomas Sinclair & Co. and John Morrell & Co., respectively), in a third phase of growth that might be called exurban industrialism (which continues in places like Worthington MN). Ice packing allowed “Midwestern outputs” to increase “fivefold, from 495,714 hogs in 1872 to 2,543,120 hogs in 1877” and made packing a year-round process. In the 1880s and 1890s, major packers diversified into beef, using refrigerated freight cars. Walsh did not describe the process but said this led directly to “Big business...in the shape of the Big Five” companies that dominated meat processing in the 20th century (Armour, Swift, Wilson, Morris, and Cudahay Packing). The critics were universally positive, with the exception of a cranky Chicago labor historian who had apparently wanted a social history rather than an economic history.

Was this the kind of packing that gave Green Bay, Wisconsin's NFL team their name?

As soon as you brought up Cincinnati, I remembered Les Nessman from "WKRP", since agriculture was his main beat as a reporter.

I thought so....