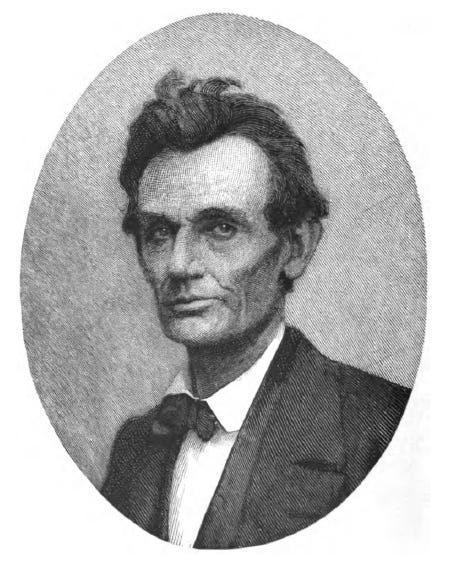

Letters from President-elect Abraham Lincoln

To William Kellogg

December 11, 1860. Entertain no proposition for a compromise in regard to the extension of slavery. The instant you do they have us under again: all our labor is lost and sooner or later must be done over. Douglas is sure to be again trying to bring in his "popular sovereignty." Have none of it. The tug has to come and better now than later. You know I think the fugitive-slave clause of the Constitution ought to be enforced — to put it in its mildest form, ought not to be resisted.

To General Duff Green

December 28, 1860. My Dear Sir, I do not desire any amendment of the Constitution.

Recognizing however, that questions of such amendment rightfully belong to the American people, I should not feel justified nor inclined to withhold from them if I could, a fair opportunity of expressing their will thereon through either of the modes prescribed in the instrument.

In addition I declare that the maintenance inviolate of the rights of the States and especially the right of each State to order and control its own domestic institutions according to its own judgment exclusively, is essential to that balance of powers on which the perfection and endurance of our political fabric depend. And I denounce the lawless invasion by armed force of the soil of any State or Territory, no matter under what pretext, as the gravest of crimes.

I am greatly averse to writing anything for the public at this time and I consent to the publication of this only upon the condition that six of the twelve United States senators for the States of Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Florida, and Texas shall sign their names to what is written on this sheet below my name and allow the whole to be published together.

Yours truly, A. Lincoln.

We recommend to the people of the States we represent respectively, to suspend all action for dismemberment of the Union at least until some act deemed to be violative of our rights shall be done by the incoming administration.

To William H. Seward

February 1, 1861. On the 21st ult. Hon W. Kellogg, a Republican member of Congress of this State, whom you probably know, was here in a good deal of anxiety seeking to ascertain to what extent I would be consenting for our friends to go in the way of compromise on the now vexed question. While he was with me I received a dispatch from Senator Trumbull, at Washington, alluding to the same question and telling me to await letters. I therefore told Mr. Kellogg that when I should receive these letters posting me as to the state of affairs at Washington, I would write to you, requesting you to let him see my letter. To my surprise, when the letters mentioned by Judge Trumbull came they made no allusion to the "vexed question." This baffled me so much that I was near not writing you at all, in compliance to what I have said to Judge Kellogg. I say now however, as I have all the while said, that on the territorial question — that is the question of extending slavery under the national auspices — I am inflexible. I am for no compromise which assists or permits the extension of the institution on soil owned by the nation. And any trick by which the nation is to acquire territory and then allow some local authority to spread slavery over it, is as obnoxious as any other. I take it that to effect some such result as this and to put us again on the highroad to a slave empire, is the object of all these proposed compromises. I am against it. As to fugitive slaves, District of Columbia, slave-trade among the slave States, and whatever springs of necessity from the fact that the institution is amongst us, I care but little, so that what is done be comely and not altogether outrageous. Nor do I care much about New Mexico, if further extension were hedged against.

Source: Abraham Lincoln, Complete Works (1894), I, 657-669. https://archive.org/details/americanhistoryt00ivunse/page/202/mode/2up