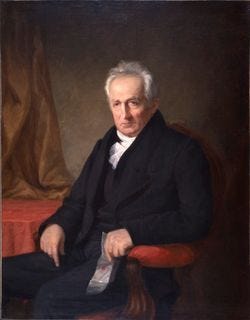

Nathan Smith

Research Notes

Nathan Smith was the founder of Dartmouth’s medical school, and its first professor. These are some excerpts from his Introductory Lecture on the Progress of Medical Science delivered at Yale in 1813 along with my comments. Timothy Dwight, president of the college, was extremely skeptical about Smith’s hiring. Not based on any technical considerations, but solely on Smith’s potential “infidelity”, especially as demonstrated by his willingness to dissect human corpses. Here are my notes and thoughts:

It has been stated by some historians that before Hippocrates lived the profession of physician was usurped by the priests; and that they had some share of the practice, or pretended to the knowledge of remedies, is more than probable; even since the Christian era this has been the case in certain countries; for instance, the Jesuits introduced the use of the Cinchona or Peruvian Bark as a remedy for intermittents [intermittent fevers] and kept it as a secret for some time; from them it had the name of Jesuits’ bark. But notwithstanding the interference of priests in the practice of medicine…

I can’t help thinking he’s talking about his present situation. Smith was forced to declare himself a Christian and prove that his religious beliefs were up to Timothy Dwight’s high standards, before the “Pope of Connecticut” would allow Smith to come start the medical school at Yale. Clever, how he hides his criticism under a jab at the papists, which Dwight and his people would love, not realizing “the interference of priests in the practice of medicine” wasn’t limited to the old days or Catholicism.

Smith continues his surreptitious digs at Dwight and the powers at Yale, remarking that there was mention of physicians “in the Old Testament, and especially in the Apocryphal writings,” but significantly not in the new testament. This construction reinforces Smith’s hidden implication that there’s something a bit anti-medical about Christianity as currently practiced.

Next, Smith gives a brief account of Hippocrates, whom he just happens to describe using the language of the new “German” biblical study that’s casting doubt on the accuracy of the gospel stories. He talks about “writings which are attributed to Hippocrates,” explaining:

That there was such a person as Hippocrates, who lived about the time above stated, and who was greatly celebrated for his skill in curing diseases, I believe is not doubted by any, but that we have received all his writings, or that all that have passed under his name were actually written by him, has been doubted by some, and if we consider that when Hippocrates lived, books were written and not printed, and, of course, that the copies must be few and the knowledge of them confined to a small number; and, further, if we consider that they were preserved in this way for many ages, we shall have some reason to doubt whether those books which have been attributed to Hippocrates were all genuine.

There’s literally no point going into this type of discussion about the doubtful attribution of Hippocrates, in a lecture preparing a class to study medicine. There’s all kinds of relevance, if he’s actually talking about the relationship between the medicine he’s preparing to teach, which is empirical, and other books of doubtful attribution.

Smith then remarks that the difference in medical knowledge between the moderns and the ancients “does not depend on the superior understanding of modern folks,” some of whom have shown themselves in contesting his nomination to be as superstitious and unreasonable as ancients. Instead, it depends on the difficulty Hippocrates had learning from experience. “It has been justly said,” Smith argues, using the materialist’s favorite argument, “that men can reason but from what they know.” Unfortunately, Hippocrates was almost totally ignorant of anatomy and physiology. A man so devoted to the development of medicine would “gladly have embraced the study of anatomy if the superstitious people would have permitted it.”

“This pernicious idolatry of mankind with respect to dead bodies,” Smith says, “kept men almost wholly ignorant of the structure of their own bodies nearly 2000 years…and still continues to harass those who attempt to enlighten themselves.” He’s clearly referring to the trouble over dissection at Dartmouth, which he had decided to leave in 1810 when it became clear to him that “some ignorant persons” had made sure his medical school would be getting no “grant or assistance voted by the Legislature to promote what they term the ‘cutting up of dead bodies’.” (Letter dated May 10, 1810 to Dr. George C. Shattuck) It’s not so clear he isn’t also referring to his new bosses at Yale.

Smith continues his historical lecture with a description of William Harvey’s discovery of the circulatory system. “Instead of being hailed with joy by the medical schools, as we should have expected,” Smith says, Harvey’s discovery “met with decided opposition by…many of the learned faculty of that day; and when at length it began to gain ground and make some noise in the world, some…were so irritated by it that they endeavored to get an additional clause added to the oath which physicians were obliged to take when they took their degree.” The problem with a circulatory system was that it challenged the classical theory of the four humors and completely invalidated the concept of bleeding a patient from certain locations for particular maladies. Scholastic philosophy’s theory of the human microcosm had led to a complete “Zodiac Man,” on which the locations and methods of bleeding were determined by studying the constellations. Aries controlled diseases of the head, Taurus the neck, etc. An empirically-discovered circulatory system shattered this human-centric ideal just as Copernicus’ observations had destroyed the earth-centered universe.