Muckraking in Minneapolis (1903)

Today I read the intro and first “chapter” of The Muckrakers by Arthur and Lila Weinberg. The first article (which I’m considering using as a primary source in my US History II course) is Lincoln Steffens’ “The Shame of Minneapolis”, from the January 1903 McClure’s Magazine. The editors say Samuel McClure leaned into muckraking because he perceived that was what his subscribers already wanted. This would be interesting if true. Probably McClure helped this interest grow.

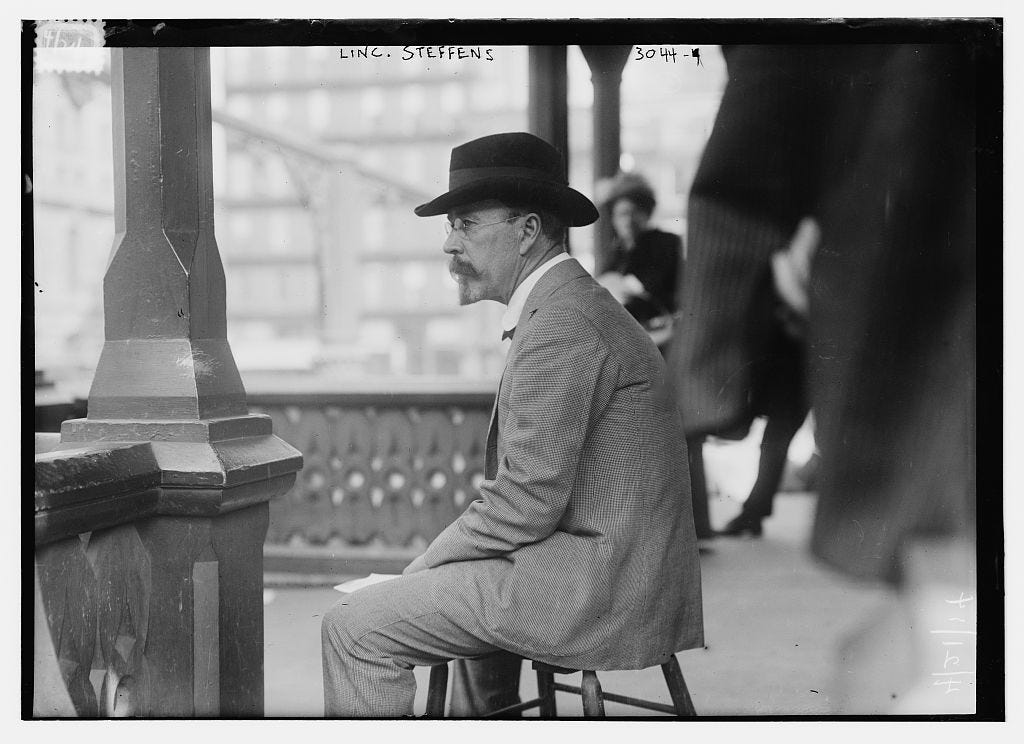

Steffens’ article about Minneapolis occupied twelve magazine pages and included photos of all the major characters he mentioned. (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015012153097&view=1up&seq=245) In addition to narrating the events of the selling out and redemption of the city, Steffens made some interesting observations. He said there are two ways in which “autocracy” can “supplant” democracy. “One is that of an organized majority” such as Tammany Hall in New York. The other is through '“the adroitly managed minority. The ‘good people’ are herded into parties and stupefied with convictions and a name, Republican or Democrat, while the ‘bad people’ are so organized or interested by the boss that he can wield their votes to enforce terms with party managers and decide elections.” (6) The villain of the story is Albert Alonzo “Doc” Ames, who Steffens described as a beloved physician who gradually became a notorious degenerate (in the caption of his photo, Steffens called Ames a “moral leper”), despised by all good people. This assessment, however, doesn’t seem evident in the 1897 book, Progressive Men of Minnesota, which described Ames in glowing terms (https://archive.org/details/progressivemenof00shut/page/64/mode/2up?view=theater). Steffens said “Doc” Ames was an opportunistic politician whose “floating minority, added to the regular partisan vote” could be a deciding factor in elections. (8) This seems especially resonant in today’s political climate.

Steffens mentioned (critically?) that Minneapolis was “strict in its laws, forbade vices which were inevitable, then regularly permitted them under certain conditions.” (10) He also said a couple of times that to some extent the citizens were to blame, since the organized crime the city officials oversaw did not “arouse” indignation or protest. Steffens announced, “No reform I ever studied has failed to bring out this phenomenon of virtuous cowardice, the baseness of the decent citizen.” (16) I wonder whether this is accurate, or is it a bit of sour grapes? If the people of Minneapolis weren’t bothered by the fact that somewhere in the city there were brothels and gambling dens, then were they base cowards? If they appreciated or tolerated a city government that kept order while preventing criminal organizations from gaining too much power, were they at fault? Toward the end of the story, Steffens approvingly described the redeemer, Percy Jones, as unwilling to compromise at all with organized crime to keep order. But he admitted in his conclusion that even Jones wasn’t entirely sure in the long run, whether a city could “be governed without any alliance with crime.” (21) So I’m not entirely sure, despite the interesting narrative and perspective, what to make of this article. I have asked my ILL librarian to get me a copy of the book Dirty Doc Ames and the Scandal that Shook Minneapolis. And I’ll be looking forward to reading more of Steffens’ muckraking.