Lady of the Rotunda

Superstition, I shall define to be the invention of the human imagination, where demonstration is not to be had, and where a system of alleged causes, falling back into a general first cause, is made of the fanciful idea of a personification of supposed principles.

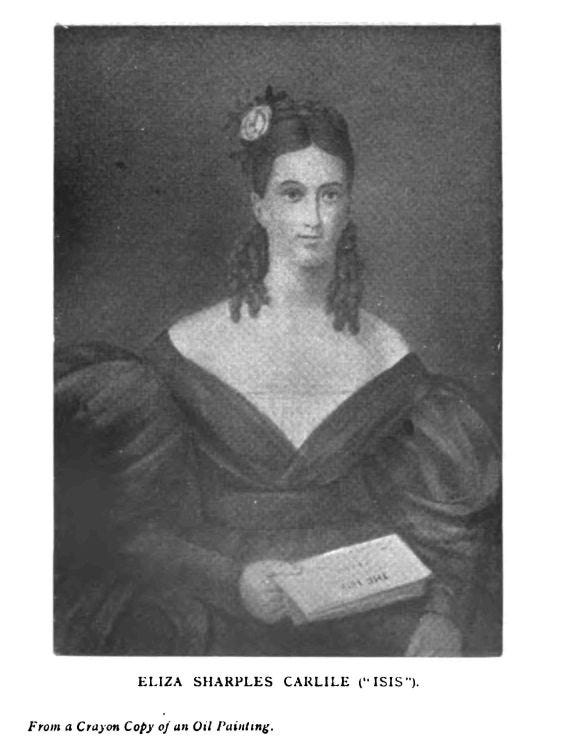

Eliza Sharples (1803-1852) was one of the first Englishwomen to lecture on freethought, radical politics, and women’s rights; possibly the first to do so in England. She was the common-law wife of Richard Carlile and mother of four children with him. While Carlile was imprisoned for seditious libel in 1832, Sharples began lecturing at his venue, the Blackfriars Rotunda, using the pseudonym Isis. Her talks briefly gained her an almost cult-like following and were reprinted in a weekly, The Isis, which she edited. When the Rotunda closed a few months later, Sharples gave her talks at Robert Owen’s theater in London.

Sharples was popular with freethinkers in America as well as England. The 15 June, 1832 Boston Investigator reprinted an article from the New York Free Enquirer. Its excerpts from Eliza Sharples’ speech began with Robert Dale Owen's description in column 2, and covered two columns. To complement Owen’s article, in the fifth column there was a reprint from the Workingman’s Advocate of a report of Robert Dale Owen’s marriage to Mary Jane Robinson, including the text of their “protest” vows. In his piece, Owen introduced Sharples with the following:

The Lady of the Rotunda.

New York, 11th May, 1832.

It needs not to repeat what every one admits, that this is an age prolific of interesting mental and moral phenomena; an age rich in prognostics of change and reform. The French Revolution, with the various novelties to which it has given birth (including the St. Simonian) is among the most marked of these. The growth of free opinion in this country is another; the boldness, sometimes verging on violence, of Richard Carlile and Robert Taylor is another; and the fact I am now about to detail is entitled to a place among the number.

A young unmarried English lady, said to be of a highly respectable and affluent family, and who conceals her name because her relations desire that it may not be published, has appeared in London, has hired “The Rotunda,” the same building where Taylor formerly lectured, delivers original lectures there twice every Sunday, and three times in the course of the week; and has commenced, on her own responsibility, a periodical entitled “The Isis.”

She delivered on the 29th January last her opening address, and repeated the same several times in the course of the ensuing week. Her lectures are thronged; how her periodical succeeds I have not heard.

I am now about to leave this city for London, and hope, while there, to see this Lady of the Rotunda, if I can procure an introduction to her.—At all events, if her lectures are continued, I shall attend them; and “report progress,” as politicians say, to our readers.

First Discourse of the Lady of the Rotunda.

The task which I propose to perform, I am told, has no precedent in this country; so I have great need of craving your indulgent attention and most gentle criticism.

A woman stands before you who has been educated and practiced in all the severity of religious discipline, awakened to the principles of reason but as yesterday, seeking on these boards a moral and a sweet revenge, for the outrage that has been committed on the majesty of that reason, and on the dignity of that truth, inasmuch as the barbaric administration of alleged law, that never had the consent of the people; of law, that has been made for the purpose, by the administrators of the law, has arrested the voices and imprisoned the persons of the two brave and talented men [Richard Carlile and Robert Taylor], who first made this building the temple of reason and truth, and who first essayed to teach the people of this country the practical importance and incalculable value of free and public oral discussion.

This, sirs, is my purpose; I appear before you to plead the cause of those injured men; to endeavor to reason before you as they reasoned before you; to follow their example, even if the sequel be a following them to a prison.

I have left a home, in a distant country, where comfort and even affluence surrounded me—a happy home, and the bosom of an affectionate and a happy family. I have left such a home, under the excitement which religious persecution has roused, to make this first and singular appearance before you, for a purpose, I trust that is second to none.

So much, by way of an introduction, where no introduction has been otherwise made. I come at once to the preliminaries of my present discourse.

Would you have from me a profession of faith?—You shall have it.

Faith, in its relation to superstition, I have none. But of faith, in the relation of the word to whatever is lovely, whatever is good, and whatever is true, whatever is morally binding and honorable, I flatter myself that I am rich, and of large possessions. At least, sirs, I submit this my faith to your most severe critical judgments.

But then, we are told, that they who have no faith in relation to superstition, are scoffers and scorners. This shall not be the seat of the scorner while it is in my hands, but the theatre of reason, of truth, and of free discussion; of an encouragement to every well expressed desire for mutual instruction. I purpose to speak, in my continued discourses, if this shall find favor with you, of superstitions and of reason, of tyranny and of liberty, of morals and of politics.

Of politics!—politics from a woman! Some will exclaim, yes, I will set before my sex the example of asserting an equality for them with their present lords and masters, and strive to teach all, yes all, that the undue submission, which constitutes slavery is honorable to none; while the mutual submission, which leads to mutual good, is to all alike dignified and honorable.

Superstition, I shall define to be the invention of the human imagination, where demonstration is not to be had, and where a system of alleged causes, falling back into a general first cause, is made of the fanciful idea of a personification of supposed principles. It would not be in vain, if man were superstitious enough to seek to make a paradise of the earth, instead of making his never-to-be-reached paradise of the conceits of his own brain. Help me sirs, in this mighty undertaking, and some of us may see that we have made the world the better for living in it.