Knowlton Endnotes

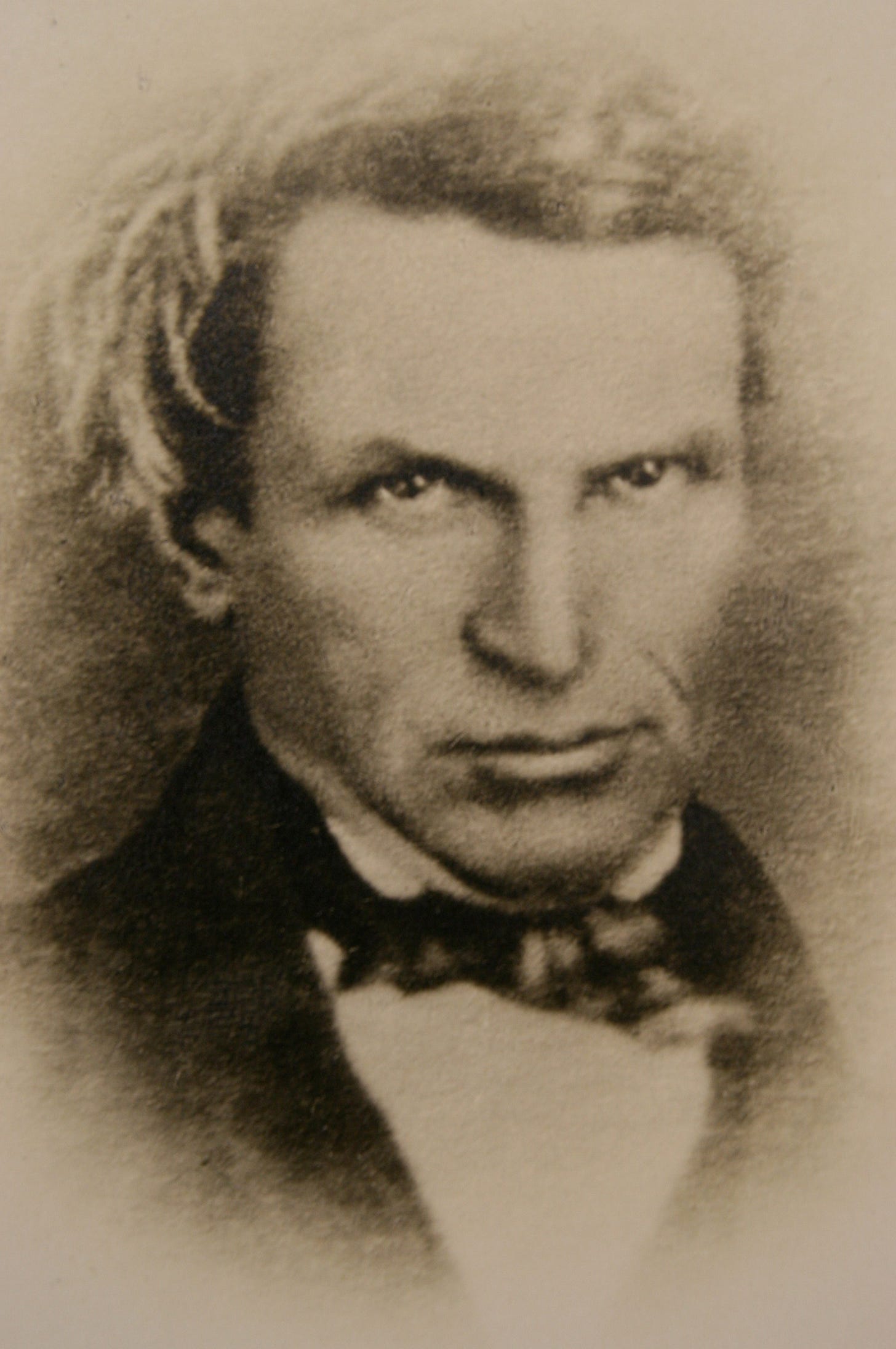

(Daguerreotype of Charles Knowlton I discovered in a file folder in Deerfield)

At the end of my biography of Dr. Charles Knowlton, I added twenty-five pages of endnotes. In addition to identifying the sources of all the passages in Knowlton's own words I had used to begin each chapter, I added some commentary and the sources of background facts. I have been paging through these, this morning, and some things have jumped out at me.

I describe History and Biography as topics that are complicated in ways that are not always apparent to readers. The challenge, writing for a general audience, is taking the theoretical stuff that only interests historians out of the spotlight and dealing with it in the background (or even backstage). My project focused on Knowlton’s story and his importance as an example of a principled outsider influencing social change in a big way. Although I tried to keep theory in the background, that doesn’t mean I was unaware of theory. Speaking plainly is not the same thing as being simple—Knowlton’s story shows us that, too. Knowlton has appeared in academic books and articles from time to time, such as Janet Farrell Brodie’s 1997 book Contraception and Abortion in 19th-Century America and Michael Sappol’s 2009 article, “The Odd Case of Charles Knowlton: Anatomical Performance, Medical Narrative, and Identity in Antebellum America,” in the Bulletin of the History of Medicine. These works and others like them pursue specific topics such as the history of birth control or the use of storytelling in identity-creation. Historians explore topics such as these by arranging the evidence they find and discarding what they consider irrelevant to the issue they’re pursuing. Even when they found a lot of great material (and both the authors I mentioned did), the object of their work was not to understand the totality of the subject’s life on his own terms, but to support their argument. Understanding Knowlton on his own terms was the object of my story.

A lot of the background details such as birth, marriage, and death dates and contemporary events and issues came from old books. At the end of the nineteenth century, a wave of nostalgia and genealogical interest caused communities around America to produce histories of their settlement and early residents. These bear titles such as A History of the Town of Keene From 1732, when the Township was Granted by Massachusetts, to 1874, when it Became a City or An Historical Discourse in Commemoration of the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Formation of the First Congregational Church in Templeton, Massachusetts. Another extremely useful tool for researchers of Massachusetts history are the Vital Records books that were published at the turn of the twentieth century, which list all the births, marriages, and deaths from a town's settlement to 1849.

There were some things I was NOT able to talk about in as much detail as I would have liked, because I lacked documentary evidence. For example, it would have been great to be able to show details of family life during Charles' Ashfield years. His children were growing up and his protege Stephen Tabor was learning medicine and falling in love with Lucy Melvina. But there are no diaries or letters on which to base such descriptions. And most unfortunate was my inability to give Tabitha Stuart Knowlton the larger role I'm sure she deserved in the story. Charles’s relationship with Tabitha not only saved his life, it probably substantially influenced his thinking and actions. Unfortunately, Tabitha didn’t leave any records of her own I was able to find, so we only see her reflected in Charles’s writing. Charles frequently called Tabitha his “affectionate wife,” suggesting that their relationship was much more emotional than what Charles had seen growing up. And as the educated daughter of a freethinker, Tabitha was probably the inspiration if not the source of many of Charles’s ideas—especially about women and reproduction. Although I wanted to make Tabitha a larger and more well-rounded character in this story, the facts just were not available to support unqualified statements about her life and role in Charles’s story.

Finally, there are many tangential trails a researcher follows for a bit, and then puts aside to return to the main path of the story. A big tangent that tempted me while putting together the story of Knowlton involved all the other early doctors of New England. Dr. Charles Adams, for example, lived in a big house on Main Street in Keene that had once been the Wyman Tavern, where the original charter for Dartmouth College had been written in 1769. Dr. Nathan Smith, Drs. Oliver and Mussey of Dartmouth, and Dr. Amos Twitchell were also very interesting characters. I'll probably continue pursuing a story about early medicine in America and read more about these people in books like The Life and Letters of Nathan Smith, M.B., M.D. and The History of Dartmouth College. So stay tuned for that.

I'm not sure. I assumed it was, since it had to have been taken in the 1840s. Knowlton died in February 1850.

Are you sure that’s a Daguerreotype? It looks like a print from a negative to me—although it’s often hard to tell from a computer screen!