Knowlton Biography, Chapter 37

Thirty-seven: Excitement in Ashfield

It so happens, that most of the people in Ashfield, and many in the towns round about, are the strangest folks that you ever did see. They will go to just what store they please; employ just what mechanic they have mind to; and just what doctor—and all this, even without consulting the p-a-r-son!! Oh, they are a stiff necked people—a rebellious people; but yet, after all, they are not so much to blame for it; for they inherit this spirit from their forefathers—the veterans of the revolution!

Although Mason Grosvenor and his allies in Ashfield said Knowlton was spreading infidelity in the region, there is no evidence Charles ever went out of his way to teach materialism to his neighbors. “I would have it distinctly understood,” Charles said when he defended himself at the town hall, “that it is not my object, nor do I expect to make one proselyte. I care not how many devils and revelations people believe in, if I may but have the same free privilege, without sacrifice of interest or character, to honestly acknowledge my inability to believe in the same!”

As time passed and Grosvenor’s attacks became more and more strident, Charles found growing numbers of his neighbors supporting him. “I boast not of many warm friends in this town,” Charles wrote to the minister,

But free-born Americans are here, men of noble blood not a few, who, however much they may differ with me, and agree with what you profess, in mere matters of faith, will not join you in your unhallowed attempt to crush me on account of my honest opinions—opinions that are the result of more, and deeper study than you, perhaps, were ever able to bestow on any subject—certainly they will not, so long as they see me dealing justly with all, speaking evil of none, and consuming the midnight oil in the investigation of diseases to which human nature is liable.

One Ashfielder, in particular, stood as an example of the conflict and a lightning rod for public opinion. Nathaniel Clark was an old farmer and the son of an old Ashfield farmer. Overhearing a neighbor attacking Knowlton’s speech at the town hall as a “low, vulgar discourse and calculated to do infamy,” Clark joined the conversation to defend his doctor. “There never was a more dirty nasty vulgar discourse,” he said, “than was preached in our pulpit at our meeting house by Mr. Grosvenor last Sabbath.”

Clark’s comments were overheard by a member of the church leadership, who immediately told Reverend Grosvenor. The minister sent his deputies to demand that Clark retract his statements and apologize for them in front of the congregation. The old farmer first denied criticizing Grosvenor’s sermon, then he denied his opinions were anyone’s business except the people he had said them to. Finally, Clark admitted saying he had never heard such unchristian talk as the most recent sermon Grosvenor had given against Knowlton. It was unfit for young ears, Clark elaborated, and he wouldn’t bring his children into the church to hear that kind of hatred from the pulpit. Clark refused to apologize or take back his comments. So Grosvenor convened an emergency meeting of the church leaders, and after leading them in prayer he insisted they excommunicate Nathaniel Clark.

Excommunication in a New England town in 1834 meant shunning. Friends and neighbors were no longer able to speak with Clark. Even members of his family was expected to distance themselves from him or suffer the same fate. This punishment for saying what many others believed but had been afraid to say was devastating to a man who’d lived in Ashfield all his life. After several weeks of silence, Nathaniel Clark began trying to reconcile with the congregation. The distrust and bad feelings between Clark and the church leaders, however, had reached a level where a council of ministers from other area churches had to be formed to review the dispute and resolve the affair. It was over two years before Clark was once again considered a member of the community.

Another area farmer named Samuel Ranney had even less patience with the bigots of Ashfield. As part of his crusade to revive religion in Ashfield, Reverend Grosvenor had begun mailing “admonishments” to delinquent members of the congregation. In April, 1834, the minster wrote to Ranney and accused him of breaking his covenant vows by failing to attend services and by not paying his Church Tax. Grosvenor still thought supporting the church should be mandatory, in spite of the fact that the Congregational Church had been disestablished—had lost its legal right to assess taxes on Massachusetts residents at the beginning of the year. The minister ordered Ranney to reflect on his duty and the eternal consequences of making the wrong decision—and to get back to him before the church’s executive committee met in a couple of weeks to deal with his case.

Unlike Nathaniel Clark, Samuel Ranney actually was well on his way to becoming a freethinker. He was also a successful businessman, who had introduced Ashfielders to growing and distilling peppermint oil. Essential oils and the peddlers who sold them throughout the United States had become Ashfield’s biggest business and had literally put the little town on the national map. Ranney thought about Mason Grosvenor’s letter for a couple of days, and then wrote his response.

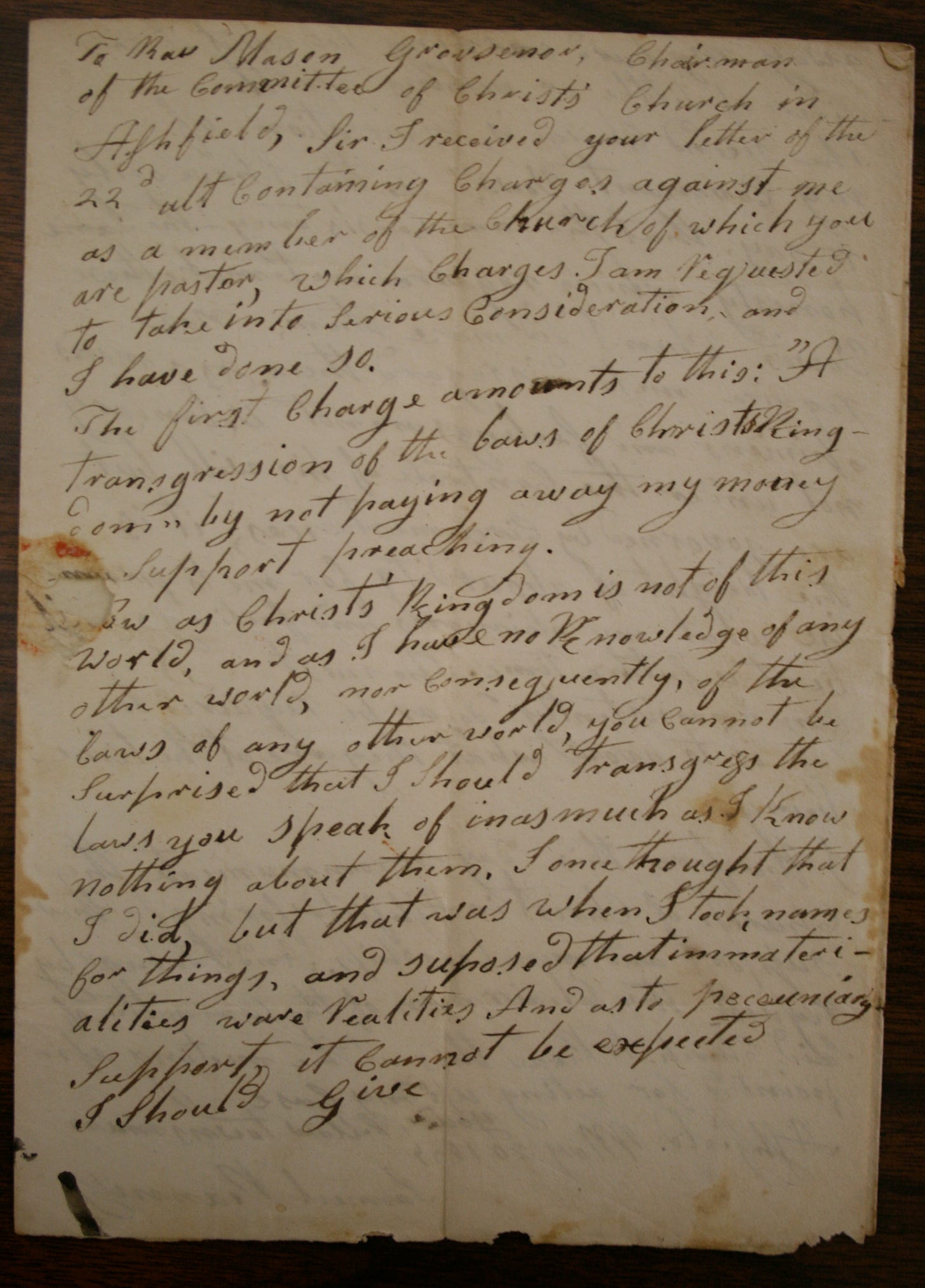

“The first charge amounts to this,” Ranney wrote. “‘A transgression of the laws of Christ’s Kingdom’ by not paying away my money to support preaching.”

Now as Christ’s Kingdom is not of this world, and as I have no knowledge of any other world, nor consequently of the laws of any other world, you should not be surprised that I should transgress the laws you speak of inasmuch as I know nothing about them. I once thought that I did, but that was when I took names for things, and supposed that immaterialities were realities. And as to pecuniary support, it cannot be expected I should give away my hard earning for what I consider of little or nothing worth.

The second charge against Ranney was that he had violated his “Covenant Vows,” which required him to attend Grosvenor’s sermons and to believe the church’s teachings. Ranney responded that he no longer believed, and “the same honesty which required me to make these vows when I did make them, now requires me to disregard them.” Since Ranney no longer believed in “immaterialities” and had no intention of supporting them with his time or money, the next step was simple. Rather than waiting for the church to punish him, Samuel Ranney concluded his letter, “I therefore this day excommunicate the Church of Christ in Ashfield from my further support and membership.” Ranney took the church’s ultimate penalty, and turned it against them.

It’s uncertain whether Samuel Ranney learned that names were not things and that “immaterialities” were not realities from Charles Knowlton, although the Knowlton and Ranney families remained on close terms for decades. If he did, Ranney would be one of very few Ashfielders who became freethinkers after knowing Charles. What is certain is that Samuel Ranney, his brother George, and their cousin Roswell all sold their farms, liquidated their investments in Ashfield, and moved their large families to upstate New York, taking the lucrative peppermint oil business with them. And the Ranneys weren’t the only people to leave Grosvenor’s church. The voting membership of the Congregational Church in Ashfield dropped from one hundred forty-six families in 1831, before Knowlton and Grosvenor arrived, to only fifty families five years later. Although they had rejected their minister’s attacks on freethought, most of the people who quit the church did not become materialists. Charles Knowlton didn’t pull Ashfielders away from religion—Mason Grosvenor pushed them.