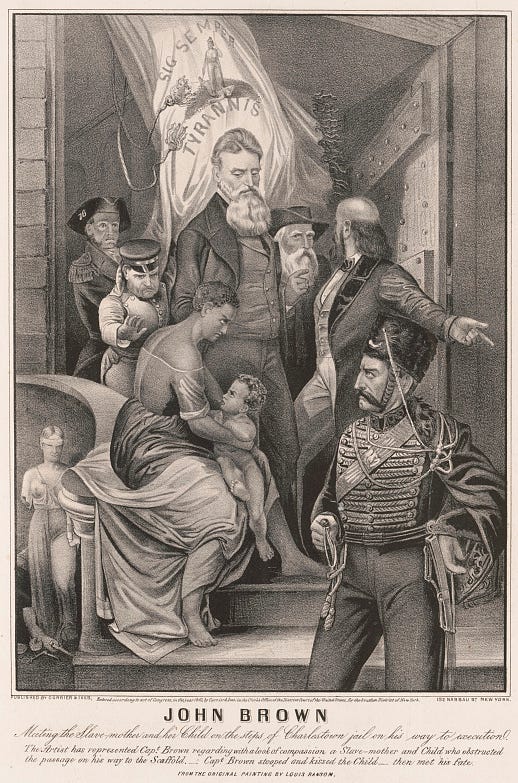

John Brown depicted as Christ, en route to his execution, with a black mother and her mulatto child. Above his head is the flag of Virginia, and its motto, Sic semper tyrannis. Currier and Ives print, 1863

Mr. Mason — If you would tell us who sent you here — who provided the means — that would be information of some value.

Mr. Brown — I will answer freely and faithfully about what concerns myself — I will answer anything I can with honor — but not about others.

Mr. Vallandigham (member of Congress from Ohio who had just entered) — Mr. Brown, who sent you here?

Mr. Brown — No man sent me here. It was my own prompting and that of my Maker or that of the devil, whichever you please to ascribe it to. I acknowledge no master in human form.

Mr. Vallandigham — Did you get up the expedition yourself?

Mr. Brown — I did.

Mr. Mason — How many are engaged with you in this movement? I ask those questions for our own safety.

Mr. Brown — Any questions that I can honorably answer I will, not otherwise. So far as I am myself concerned I have told everything truthfully. I value my word, sir.

Mr. Mason — What was your object in coming?

Mr. Brown — We came to free the slaves and only that.

A Young Man (in the uniform of a volunteer company) — How many men in all had you?

Mr. Brown — I came to Virginia with eighteen men only, besides myself.

Volunteer — What in the world did you suppose you could do here in Virginia with that amount of men?

Mr. Brown — Young man, I don't wish to discuss that question here.

Volunteer — You could not do anything.

Mr. Brown — Well, perhaps your ideas and mine on military subjects would differ materially.

Mr. Mason — How do you justify your acts?

Mr. Brown — I think, my friend, you are guilty of a great wrong against God and humanity — I say it without wishing to be offensive — and it would be perfectly right for anyone to interfere with you so far as to free those you willfully and wickedly hold in bondage. I do not say this insultingly.

Mr. Mason — I understand that.

Mr. Brown — I think I did right and that others will do right who interfere with you at any time and all times. I hold that the golden rule, "Do unto others as you would that others should do unto you," applies to all who would help others to gain their liberty.

Lieut. Stewart — But you don't believe in the Bible.

Mr. Brown — Certainly I do.

Mr. Vallandigham — When in Cleveland did you attend the Fugitive Slave Law Convention there?

Mr. Brown — No. I was there about the time of the sitting of the court to try the Oberlin rescuers.

Mr. Vallandigham — Did you see anything of Joshua R. Giddings there?

Mr. Brown — I did meet him.

Mr. Vallandigham — Will you answer this: Did you talk with Giddings about your expedition here?

Mr. Brown — No I won't answer that, because a denial of it I would not make and to make any affirmation of it I should be a great dunce.

Mr. Vallandigham — Have you had any correspondence with parties at the North on the subject of this movement?

Mr. Brown — I have had correspondence.

A Bystander — Do you consider this a religious movement?

Mr. Brown — It is, in my opinion, the greatest service a man can render to God.

Bystander — Do you consider yourself an instrument in the hands of Providence?

Mr. Brown — I do.

Bystander — Upon what principle do you justify your acts?

Mr. Brown — Upon the golden rule. I pity the poor in bondage that have none to help them. That is why I am here; not to gratify any personal animosity, revenge, or vindictive spirit. It is my sympathy with the oppressed and the wronged, that are as good as you and as precious in the sight of God.

Bystander — Certainly. But why take the slaves against their will?

Mr. Brown — I never did . I want you to understand gentlemen (and to the reporter of the Herald) you may report that — I want you to understand that I respect the rights of the poorest and weakest of colored people oppressed by the slave system, just as much as I do those of the most wealthy and powerful. That is the idea that has moved me, and that alone. We expected no reward except the satisfaction of endeavoring to do for those in distress and greatly oppressed as we would be done by. The cry of distress of the oppressed is my reason, and the only thing that prompted me to come here.

A Bystander — Why did you do it secretly?

Mr. Brown — Because I thought that necessary to success; no other reason.

Bystander — And you think that honorable? Have you read Gerrit Smith's last letter?

Mr. Brown — What letter do you mean?

Bystander — The New York Herald of yesterday in speaking of this affair mentions a letter in this way:

Apropos of this exciting news, we recollect a very significant passage in one of Gerrit Smith's letters, published a month or two ago, in which he speaks of the folly of attempting to strike the shackles off the slaves by the force of moral suasion or legal agitation and predicts that the next movement made in the direction of negro emancipation would be an insurrection in the South.

Mr. Brown — I have not seen the New York Herald for some days past but I presume from your remark about the gist of the letter that I should concur with it. I agree with Mr. Smith that moral suasion is hopeless. I don't think the people of the slave States will ever consider the subject of slavery in its true light till some other argument is resorted to than moral suasion.

Mr. Vallandigham — Did you expect a general rising of the slaves in case of your success?

Mr. Brown — No sir; nor did I wish it. I expected to gather them up from time to time and set them free.

Mr. Vallandigham — Did you expect to hold possession here till then?

Mr. Brown — Well, probably I had quite a different idea. I do not know that I ought to reveal my plans. I am here a prisoner and wounded, because I foolishly allowed myself to be so. You overrate your strength in supposing I could have been taken if I had not allowed it. I was too tardy after commencing the open attack — in delaying my movements through Monday night and up to the time I was attacked by the government troops. It was all occasioned by my desire to spare the feelings of my prisoners and their families and the community at large. I had no knowledge of the shooting of the negro (Heywood).

Reporter of the Herald — I do not wish to annoy you, but if you have anything further you would like to say I will report it.

Mr. Brown — I have nothing to say, only that I claim to be here in carrying out a measure I believe perfectly justifiable and not to act the part of an incendiary or ruffian, but to aid those suffering great wrong. I wish to say furthermore, that you had better — all you people at the South — prepare yourselves for a settlement of that question that must come up for settlement sooner than you are prepared for it. The sooner you are prepared the better. You may dispose of me very easily. I am nearly disposed of now. But this question is still to be settled — this negro question I mean. The end of that is not yet.

Bystander — To set them free would sacrifice the life of every man in this community.

Mr. Brown — I do not think so.

Bystander — I know it. I think you are fanatical.

Mr. Brown — And I think you are fanatical. "Whom the gods would destroy they first made mad," and you are mad.

Source: New York Herald, October 21, 1859. https://archive.org/details/americanhistoryt00ivunse/page/146/mode/2up

"Whom the Gods would destroy, they first made mad." And they still do in the 21st century.