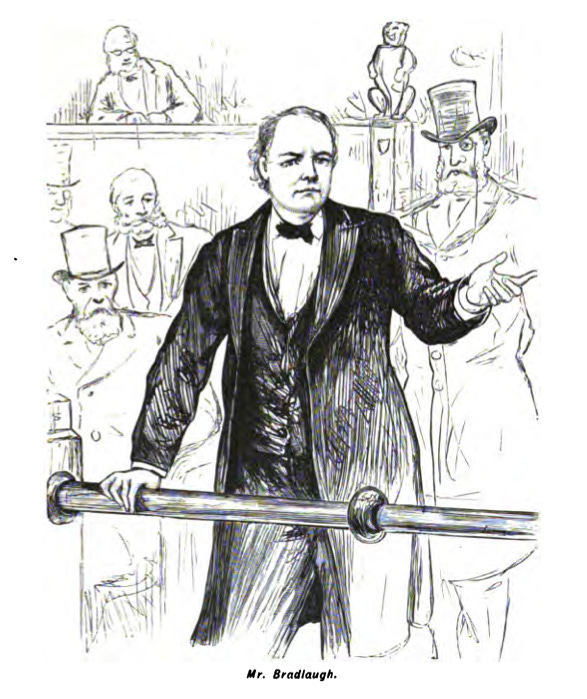

Introducing Charles Bradlaugh

The men in the crowd had come from all over England. They had rallied in Trafalgar Square the night before, to show the press and the public they were serious. Charles Bradlaugh had spoken to the large crowd; thanking them for electing him to Parliament and promising to go on fighting for their rights.

They had come to London by the thousands to demand that after three months of delays, the candidate they’d elected to champion their cause in the House of Commons should be allowed to enter Parliament and take his seat. Since the election, his Tory opponents had barred him from the chamber because they declared that as an atheist he was unfit to take the religious oath of office. But the crowd knew this was a sham. There were other atheists in Parliament. Bradlaugh was blocked because he was known throughout England as a radical and an advocate for working people.

Charles Bradlaugh approached the members’ entrance to the House the following morning, a crowd of four thousand at his back. He planned on entering alone, and presenting himself “at the bar” for the oath. He had insisted that by law they would have to allow him, and he didn’t want to give his opponents any excuses. He asked the crowd to wait for him at the public entrance. His last instructions were to his second-in-command, Annie Besant.

“I want no demonstrations,” Bradlaugh said. “No violence, whatever happens.”

“This crowd is tiny,” she insisted. “You can force this issue. Cromwell had fewer men behind him.”

“If I don’t respect the law,” he answered sternly, “I can’t expect the government to do so.” He stared at her until she squared her shoulders and nodded her assent. “The people know you better than they know anyone, aside from me. Whatever happens; whatever happens, they are to do no violence. I’m trusting you to keep them under control.”

“Yes, sir.” she answered.

Annie led the crowd to the public entrance and the lobby of the House. They had come with dozens of petitions from all over England, demanding that Parliament allow their man to take his seat. Charles Bradlaugh’s two daughters and a few petitioners were allowed in, but the crowd was held back on the excuse that there were no more seats.

“Another lie,” men muttered, and the crowd tensed. “Petitions!” someone yelled, “Justice for petitions.” By law, ten people should have been allowed to carry each petition into the chamber.

“Petitions, petitions! Justice, justice!” the crowd began to chant. It moved toward the steps like a tide. The police at the top readied for combat.

“No!” Annie Besant shouted. Her voice rang in the air as she threw herself between the crowd and the door. “For His sake, no!” she shouted again. One of the policemen behind her laughed at the idea she was going to stop the crowd. She spoke again, reminding the angry crowd that right was on their side and that Bradlaugh did not want a riot. They began to draw back.

As the crowd quieted, the people outside heard shouts and crashes. There was a roar of angry voices inside the House. Someone yelled “Kick him out!” and sounds of breaking glass and splintering wood suggested a battle was going on inside the Parliament building.

“He’s in the Palace Yard!” someone shouted. The crowd raced back to the spot where Bradlaugh had left them. They saw him standing alone, surrounded by fourteen guards and policemen. His face was bloody and his suit was torn to tatters. He had been forcibly ejected from the House of Commons and had fought the guards every inch of the way.

The crowd was silent, aghast. Charles Bradlaugh’s chest heaved with exertion and his limbs shook. It had taken fourteen men to push and drag his sturdy six-foot frame out of the building. But his face was pale as death. He gathered himself and stepped up to the Sergeant of the Guard. He faced the Sergeant, the guards, and the opposing Members of Parliament who had followed at a safe distance hoping to see a fight. Very quietly, he said “I can come back with enough strength to force this door.”

“When?” asked the Sergeant.

“Right now, if I raise my hand,” Bradlaugh answered.

The Sergeant looked past the battered man, at the thousands. He imagined these men overpowering his guards, storming the House of Commons, and throwing the opposing Members who had illegally denied their rights out the windows into the stinking Thames.

“I don’t doubt it,” he whispered.

Bradlaugh paused. He imagined the same scene and he knew there was nothing standing in his way. He could occupy the House and force it to obey its own laws. He could lead a Civil War against the Lords and Tories, and even against the so-called Liberals who denied had his rights and ignored the people’s suffering for so many years. They could do away with the corrupt, wasteful Lords and useless, imperialist Monarchy, and establish a republic of England for the working people.

Charles Bradlaugh was a man of action and a born fighter. His blood beat in his head; he wanted to fight. The crowd held its breath, and he knew every man there would follow him into this battle.

“No,” Bradlaugh said. He turned his back on the door and spoke to his crowd. “No man will sleep in gaol tonight for me,” he said. “No woman will blame me for her husband killed or wounded.” He told them to disperse and meet again later at the Hall of Science. Parliament’s treachery to England and liberty would not go unanswered, he promised. But not with blood today. The crowd knew he’d devoted his life to their fight and they trusted him. Slowly they dispersed and the injured man’s friends helped him to a carriage.

(This is a dramatization: I have invented some dialog but the events actually happened as I describe them.)

Charles Bradlaugh was the greatest British radical of the nineteenth century. A brilliant orator and public debater, he was the most notorious freethinker in straitlaced, hypocritical Victorian England. Bradlaugh founded and presided over Britain’s National Secular Society for three decades. He published a radical, atheist weekly newspaper, The National Reformer, that was prosecuted several times by both Liberal and Conservative governments. He supported republican movements throughout Europe, faced imprisonment for advocating birth control, and led the movement that won the vote for English working people. But most people, even most historians, have never heard of him.

While “gentlemen” like William Gladstone, John Stuart Mill and even Karl Marx are well-remembered for what they wrote and said in nineteenth-century London, Charles Bradlaugh is forgotten because his realm was action. And also because he came from the lower classes and thrust uncomfortable causes and ideas into the public eye. Polite Victorian society would have liked nothing better than to ignore him, but they were unable to brush him aside. So they did the next best thing and virtually erased him from history.

This section of Freethought History is devoted to the story of Bradlaugh’s life and also of his times. In order to understand why Charles Bradlaugh became an atheist, a radical, a republican, and a champion of Ireland, land reform, and the working class, it’s necessary to understand the world he was born into and the society in which he lived. This means looking deeper than the thin veneer of upper and upper-middle class London society, where most historians seem to believe history was made. If the voices of regular people have any meaning in history, then the story of a man who led and spoke for hundreds of thousands when they met in Hyde Park to demand the right to vote should be told.

There have been a few biographies of Charles Bradlaugh. One was written with his cooperation when he was middle-aged; another was written by his political opponents and later ruled libelous and outlawed. Bradlaugh’s daughter Hypatia wrote a two-volume biography two years after his death, partly in an attempt to defend his memory from ongoing libels by his political foes. All three were written by and for contemporaries, so they assume familiarity with people, places, and events that the present-day reader lacks. More recent books about Bradlaugh tend to focus in depth on a particular aspect of his life, like his atheism or his exclusion from Parliament. But they miss the context and significance of Bradlaugh’s story for a wider audience.

Charles Bradlaugh worked his way from poverty to notoriety, struggled to rise in the world while remaining true to his ideals, and he battled throughout his life against hypocrisy and bigotry. He lived in a remarkable time and his life is best understood with an appreciation of the world in which he lived. So in addition to chronicling the events of his life, this section will describe the setting and context of Bradlaugh’s story.