Indian Opinion of the White Man (1817)

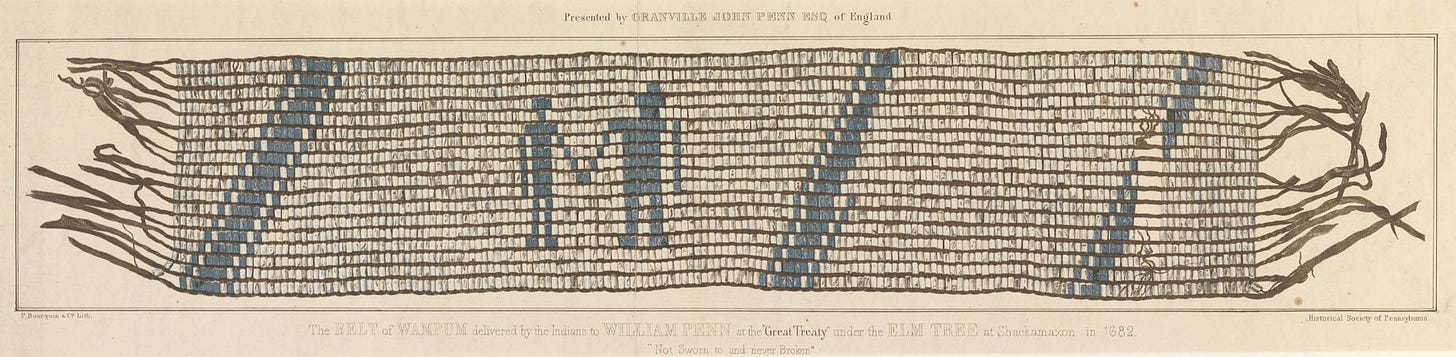

Wampum belt given to Miquon (William Penn) at the "Great Treaty" of 1682.

Long and dismal are the complaints which the Indians make of European ingratitude and injustice. They love to repeat them and always do it with the eloquence of nature, aided by an energetic and comprehensive language which our polished idioms cannot imitate. Often I have listened to these descriptions of their hard sufferings until I felt ashamed of being a white man.

They begin with the Virginians, whom they call the long knives and who were the first European settlers in this part of the American continent. "It was we", say the Lenape, Mohicans, and their kindred tribes, "who so kindly received them on their first arrival into our country. We took them by the hand and bid them welcome to sit down by our side and live with us as brothers. But how did they requite our kindness? They at first asked only for a little land on which to raise bread for themselves and their families and pasture for their cattle, which we freely gave them. They soon wanted more, which we also gave them. They saw the game in the woods which the Great Spirit had given us for our subsistence and they wanted that too. They penetrated into the woods in quest of game, they discovered spots of land which pleased them. That land they also wanted and because we were loth to part with it, as we saw they had already more than they had need of, they took it from us by force and drove us to a great distance from our ancient homes."

"By and by the Dutchemaan arrived at Manahachtanienk. The great man wanted only a little, little land on which to raise greens for his soup, just as much as a bullock's hide would cover. Here we first might have observed their deceitful spirit. The bullock's hide was cut up into little strips, and did not cover, indeed, but encircled a very large piece of land which we foolishly granted to them. They were to raise greens on it, instead of which they planted great guns. Afterwards they built strong houses, made themselves masters of the island, then went up the river to our enemies the Mengwe [Iroquois], made a league with them, persuaded us by their wicked arts to lay down our arms, and at last drove us entirely out of the country.

"When the Yengeese arrived at Machtitschwanne they looked about everywhere for good spots of land and when they found one, they immediately and without ceremony possessed themselves of it. We were astonished but still we let them go on, not thinking it worthwhile to contend for a little land. But when at last they came to our favorite spots, those which lay most convenient to our fisheries, then bloody wars ensued. We would have been contented that the white people and we should have lived quietly beside each other, but these white men encroached so fast upon us that we saw at once we should lose all if we did not resist them. The wars that we carried on against each other were long and cruel. At last they got possession of the whole of the country which the Great Spirit had given us. One of our tribes was forced to wander far beyond Quebec, others dispersed in small bodies and sought places of refuge where they could. Some came to Pennsylvania, others went far to the westward and mingled with other tribes.

"To many of those, Pennsylvania was a last, delightful asylum. But here again, the Europeans disturbed them and forced them to emigrate, although they had been most kindly and hospitably received. On whichever side of the Lenapewihittuck the white people landed, they were welcomed as brothers by our ancestors who gave them lands to live on and even hunted for them and furnished them with meat out of the woods. Such was our conduct to the white men who inhabited this country until our elder brother, the great and good Miquon [William Penn] came and brought us words of peace and good will. We believed his words and his memory is still held in veneration among us. But it was not long before our joy was turned into sorrow. Our brother Miquon died and those of his good counsellors who were of his mind and knew what had passed between him and our ancestors were no longer listened to. The strangers who had taken their places no longer spoke to us of sitting down by the side of each other as brothers of one family, they forgot that friendship which their great man had established with us and was to last to the end of time. They now only strove to get all our land from us by fraud or by force and when we attempted to remind them of what our good brother had said, they became angry and sent word to our enemies the Mengwe to meet them at a great council which they were to hold with us at Loehauwake, where they should take us by the hair of our heads and shake us well. The Mengwe came, the council was held, and in the presence of the white men who did not contradict them they told us that we were women and that they had made us such. That we had no right to any land because it was all theirs, that we must be gone, and that as a great favor they permitted us to go and settle further into the country at the place which they themselves pointed out at Wyoming.

"We and our kindred tribes lived in peace and harmony with each other before the white people came into this country. Our council house extended far to the north and far to the south. In the middle of it we would meet from all parts to smoke the pipe of peace together. When the white men arrived in the south, we received them as friends. We did the same when they arrived in the east. It was we, it was our forefathers, who made them welcome and let them sit down by our side. The land they settled on was ours. We knew not but the Great Spirit had sent them to us for some good purpose and therefore we thought they must be a good people. We were mistaken, for no sooner had they obtained a footing on our lands than they began to pull our council house down first at one end and then at the other. And at last meeting each other at the center, where the council fire was yet burning bright, they put it out and extinguished it with our own blood! With the blood of those who with us had received them! Who had welcomed them in our land! Their blood ran in streams into our fire and extinguished it so entirely that not one spark was left us whereby to kindle a new fire. The whites will not rest contented until they shall have destroyed the last of us and made us disappear entirely from the face of the earth."

I have given here only a brief specimen of the charges which they exhibit against the white people. There are men among them who have by heart the whole history of what took place between the whites and the Indians since the former first came into their country and relate the whole with ease and with an eloquence not to be imitated. On the tablets of their memories they preserve this record for posterity. I at one time in April 1787 was astonished when I heard one of their orators, a great chief of the Delaware nation, go over this ground, concluding in these words: "I admit there are good white men but they bear no proportion to the bad. The bad must be the strongest, for they rule. They do what they please. They enslave those who are not of their color, although created by the same Great Spirit who created us. They would make slaves of us if they could but as they cannot do it, they kill us! There is no faith to be placed in their words. They are not like the Indians who are only enemies while at war and are friends in peace. They will say to an Indian, 'my friend! my brother!' They will take him by the hand and at the same moment destroy him. And so you (addressing himself to the Christian Indians) will also be treated by them before long. Remember! That this day I have warned you to beware of such friends as these. I know the long knives. They are not to be trusted."

Eleven months after this speech was delivered by this prophetic chief, ninety-six of the same Christian Indians, about sixty of them women and children, were murdered at the place where these very words had been spoken by the same men he had alluded to and in the same manner that he had described.

Source: John Heckewelder, An Account of the History, Manners, and Customs, of the Indian Nations, who once Inhabited Pennsylvania and the Neighbouring States, in American Philosophical Society, Transactions of the Historical and Literary Committee (1819), I, 59-65. https://archive.org/details/toldcontemporari03hartrich/page/466/mode/2up