History and Science

This was a post I did for my own blog and then sent to The Historical Society several years ago, when I was a grad student. I think it’s an interesting example of combining historical ideas with up-to-date scientific findings.

Everyone is more or less aware that one of the major changes that began the European Enlightenment and brought about the modern world was the realization that the Earth was not the center of the universe. Through a series of discoveries, often fiercely opposed by protectors of the status quo, western cultures slowly embraced the idea that the universe is much bigger than we had previously believed. But maybe we ought to consider how recent many of these discoveries were and how new information is coming to light almost daily that promises to remake our worldview all over again.

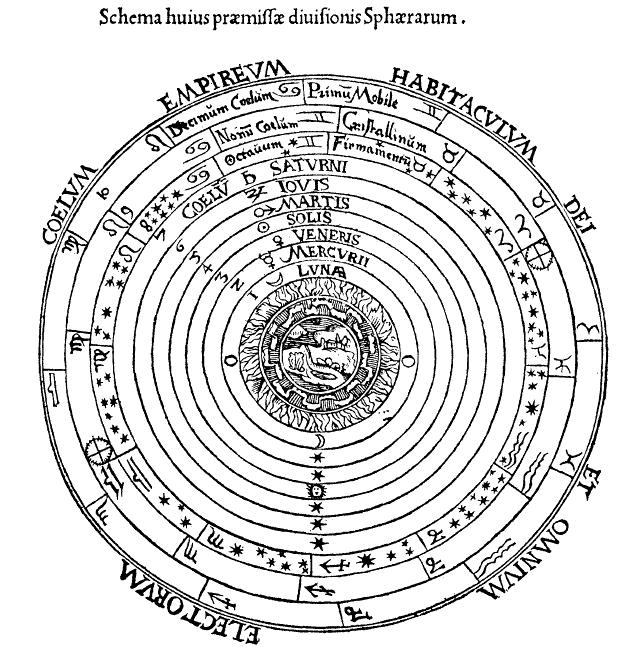

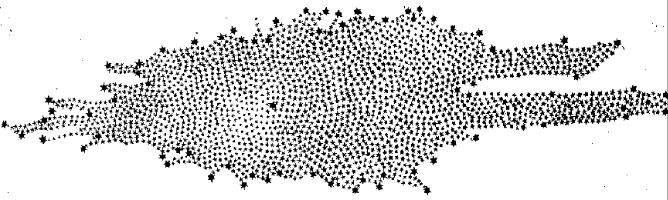

To review some of the big milestones on this journey of discovery, Renaissance astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus published his heliocentric theory, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, in 1543. Copernicus replaced the Earth with the Sun as center of the solar system, but the universe was still a smallish place, extending only to Saturn and the “fixed stars” which had been known since prehistoric times. The next planet, Uranus, was discovered by William Herschel in 1781, while his countrymen were fighting to retain their thirteen rebel colonies in America. Neptune was discovered in 1846, based on mathematical predictions made by Urbain Le Verrier to explain observed perturbations in the Uranian orbit (this was also a dramatic confirmation of Newton’s theories of gravity). But again, although our gaze had widened to include the solar system and the Milky Way, the background of more distant stars which had once been thought to all inhabit a single “sphere,” the universe was still pretty small and we were at its center. (Illustration below is the shape of our Galaxy as deduced from star counts by William Herschel; the solar system was assumed near center, as first published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1785):

Although Immanuel Kant had speculated in the eighteenth century that the Milky Way might be an “island universe,” in April, 1920, Harlow Shapley and Heber Curtis debated the structure of the universe at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. Shapley insisted that the Milky Way was the whole universe, while Curtis argued that observations of the “Andromeda Nebula” suggested it was separate from and far away from the Milky Way, which he believed was only one “island universe” among many. The existence of galaxies was finally settled by Edwin Hubble in the early 1920s, and in 1929 Hubble published his Redshift Distance law of Galaxies (now called simply Hubble’s Law), which for the first time suggested the true physical scale and immense age of the universe.

In 1930, Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto, and in 2005 a team led by M. E. Brown discovered Eris, a Trans-Neptunian Object larger than Pluto that would certainly have been hailed as the tenth planet if Pluto had not already been demoted. By 1936, when Hubble published his classification system for galaxies, we understood that the universe was much larger and much older than we had ever imagined. But we were still unique and special, many believed, because we were the only known solar system and the only place in the universe that harbored life.

Nobel physicist Enrico Fermi, in an informal discussion in 1950, suggested what has come to be known as the Fermi Paradox: if the universe is so old and so big, where is everyone? Outside science-fiction circles, however, Fermi’s question has been largely ignored. It was still possible, until the last year or so, to believe that even in a nearly unimaginably big and old universe, Earth was the oasis of life. Very recent discoveries make this belief much less tenable.

Over the last few years, astronomers have begun searching for and finding planets circling distant stars. At first, most of these “exo-planets” were gas giants many times larger than Jupiter. But as the technology (primarily space-based telescopes and earth-bound computer processing power) improved, they began to find rocky planets not much larger than Earth. To date, astronomers have mapped the locations of hundreds of exo-planets, with thousands of possibilities waiting to be examined. Even the Alpha Centauri system, our nearest stellar neighbor, is now known to have a planet only 113% the size of Earth.

The planet circling Alpha Centauri B is not Earth 2.0, however. It is too close to its star, so the surface temperature is probably much too high. In addition to believing the Milky Way was the entire universe, Harlow Shapley postulated “habitable zones” surrounding different types of stars, where liquid water could exist on a planet’s surface. Astronomers have generally regarded earth-like planets as the ideal places for life to develop, although some dissenters have pointed out that pressure as well as temperature influences the behavior of water, and there is ice on Mercury. So Shapley may have been wrong about this too, and the parameters for liquid water may be wider than just “Earth-like” worlds. But even if we restrict our search for possible havens of life to rocky planets within their stars’ habitable zones, these have now been located. And we’ve only scratched the surface.

On average, astronomers have now concluded, there are 1.6 planets for every star in our galaxy. This is news – give it a moment to sink in. Even the astronomers were surprised. There are about 100 billion stars in the Milky Way. And there may be as many “rogue planets” drifting around on their own, not associated with any particular star. There are hundreds of billions of galaxies in the observable universe. But don’t take my word for it; I’m a historian not an astronomer. Check out the links to Space Fan News, produced by the Space Telescope Science Institute’s astronomer Tony Darnell. Tony does an incredible job distilling all the latest astronomy and astrophysics headlines into weekly videos on his You Tube channel. In one of my favorites, he summed up the discoveries of the last few months: “that comes out to tens of billions of Earth-size planets that could have liquid water, in our galaxy.”

Most of these revolutions in our understanding of our place in the universe have taken some time to filter out of scientific circles. But they have also been contentious, especially when scientific discoveries challenged widely held beliefs and dogmas. I wonder, in light of all the harm religion has done to our search for the truth (and to many of the individuals who searched!), why historians are currently so fascinated with the history of religion. It was the hot new field of the 2010s, if books, articles, and professional blogs are any evidence. The Historical Society, which I was a member of, received a grant of over $1 million from the Templeton Foundation to sponsor a program and book on “Religion and Innovation in Human Affairs.” Seems like somebody out there ought to say something about the ways religion has hindered innovation, to balance all the papers that are sure to be written about how faith and progress are the best of friends. I’m really curious what will happen if we find evidence of life off Earth?

Tags: #Copernicus, #FermiParadox. #Religion