Historiography

I call my channel and substack "MakingHistory" because that's sort of the top-level thing I do. I write and talk about the past for my students at the university and for my audience online. I try to call attention to events and interpretations that are not necessarily the ones that receive the most attention. Sometimes I challenge the "master narrative", which I define as the events of the past most commonly focused upon and the explanations of why they mattered and what caused them to happen. Since history is not the past itself, but is rather narratives and claims about causality and meaning, I think what I do could be called making history.

Of course, I'm not doing anything myself that is particularly earth-shaking or history-making. I'm telling stories about the past that I think are interesting and relevant. But also, I don't just make stuff up. I like to focus my attention on combinations of people and events that may be less well known. I like interpretations and causal links that may not be widely understood or accepted. There are a lot of surprises in the past and I think exploring things that may have been accidentally forgotten or deliberately ignored may tell us things we ought to know.

One of the ways I look for a past that is not reflected in mainstream histories is by reading primary sources as much as possible, rather than relying on retrospective views. Primary sources document the ideas of people in past times, reacting to their world without a knowledge of "how the story ends". Often, people reacting in the heat of the moment can't see the full picture or have their own ideas about why things are happening or why they're important. They may be mistaken or wrong-headed, from our perspective, but they may also have ideals, commitments, and agendas we don't share and won't easily recognize if we don't try to stand in their shoes. The best way to do this is often to read their own words, rather than reports of them written by either contemporaries or historians.

That's not to say that we need to be persuaded by the things we read and get on the side of the authors. For example, I don't expect anything I read would be able to convince me that chattel slavery in the American South was a good thing. I'm not even sure I could be convinced that the people who wrote in support of slavery honestly believed the arguments they were making. As I've said previously, I think there's a big gap between rhetoric and reality, rationalization and actual motivation, which many historians seem to be unable to understand. But I also don't think that anyone I disagree with is necessarily disingenuous. I believe that people with life experiences different from my own probably have beliefs and priorities that are not obvious to me. If I want to understand them at all, a first step is trying to see the world from their perspective (obviously this applies to people in the present as well as the past, and I think it's a skill we ought to be trying to develop). A good first step is listening to them in their own words.

So that's why I'm focusing on primary sources a lot. But in addition to that, a historian's job is understanding what others are saying about the past and participating in an ongoing conversation with others about history. Not only with other historians, but also with folks in other disciplines, in politics, in the media, and in the community. When we engage with other historians, we call what results Historiography. Becoming acquainted with this conversation is a huge element of the first couple of years of grad school for academic historians. Reading and reacting to foundational texts is how we build "teaching fields" in areas like American Social or Cultural History, or Environmental History. Then we're tested (in both written and oral exams) to prove we understand the contours of these fields and have something to contribute to the discourse.

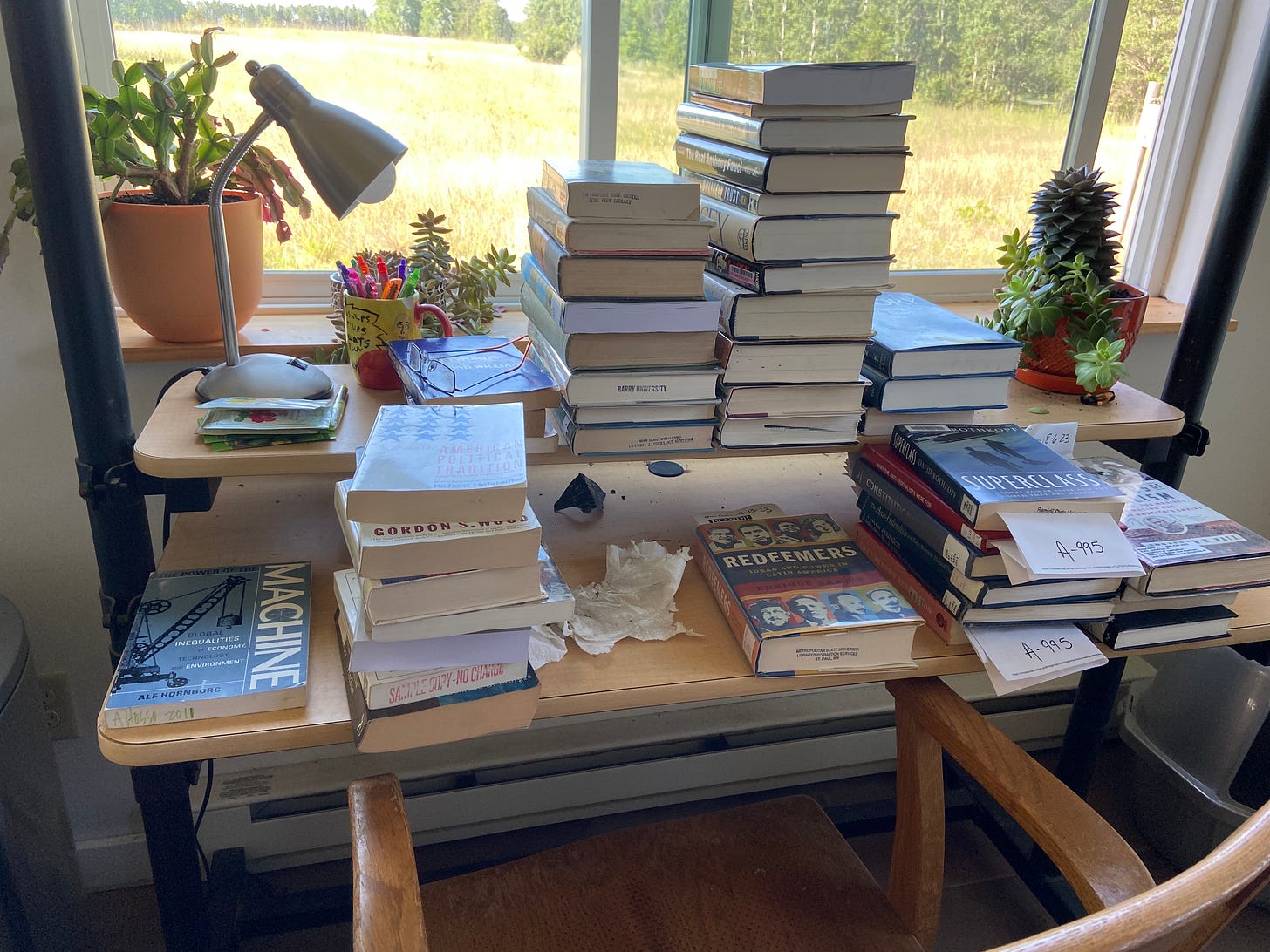

I have read a lot of books over the years, to gain these "fields" and then to maintain myself in them by keeping up with their ongoing evolution. Many of these texts have influenced the ways I understand and interpret the past -- the ways I make history. So I thought I'd start adding some of my notes on the writings of historians that have been important to me. I'll call this section "Historiography" and it will have its own tab in the menu. My reactions to these texts will of course be based on my own interests and the questions I brought to them. As they say, your mileage may vary.

I may also respond to things that people who are not professional historians say about the past. In the same way that I want to write about the past for regular people as well as for my academic peers, I care about the ways people use ideas about history to explain the present, justify their actions, or make plans. Everyone uses an understanding of the past to inform their present, so as historian Carl Becker suggested a century ago, every person is their own historian. If I end up doing a lot of this, I'll split it into its own tab on the menu. But in the meantime, you can expect to see a post on Historiography every few days.

And we so need to know history as the past ways and people influenced generations to come. Thank you, Dan, for Historiography.