Historical arguments and interesting people

As I’ve begun planning and researching my next project, following the release of my rural American history, Peppermint Kings, I’ve found myself beginning to reproduce the strategy I used in the previous book. Although this started as a more-or-less automatic approach to the topic, I’m discovering what appears to be a commitment to approaching historical questions and posing arguments in the forms of stories about interesting characters in the past.

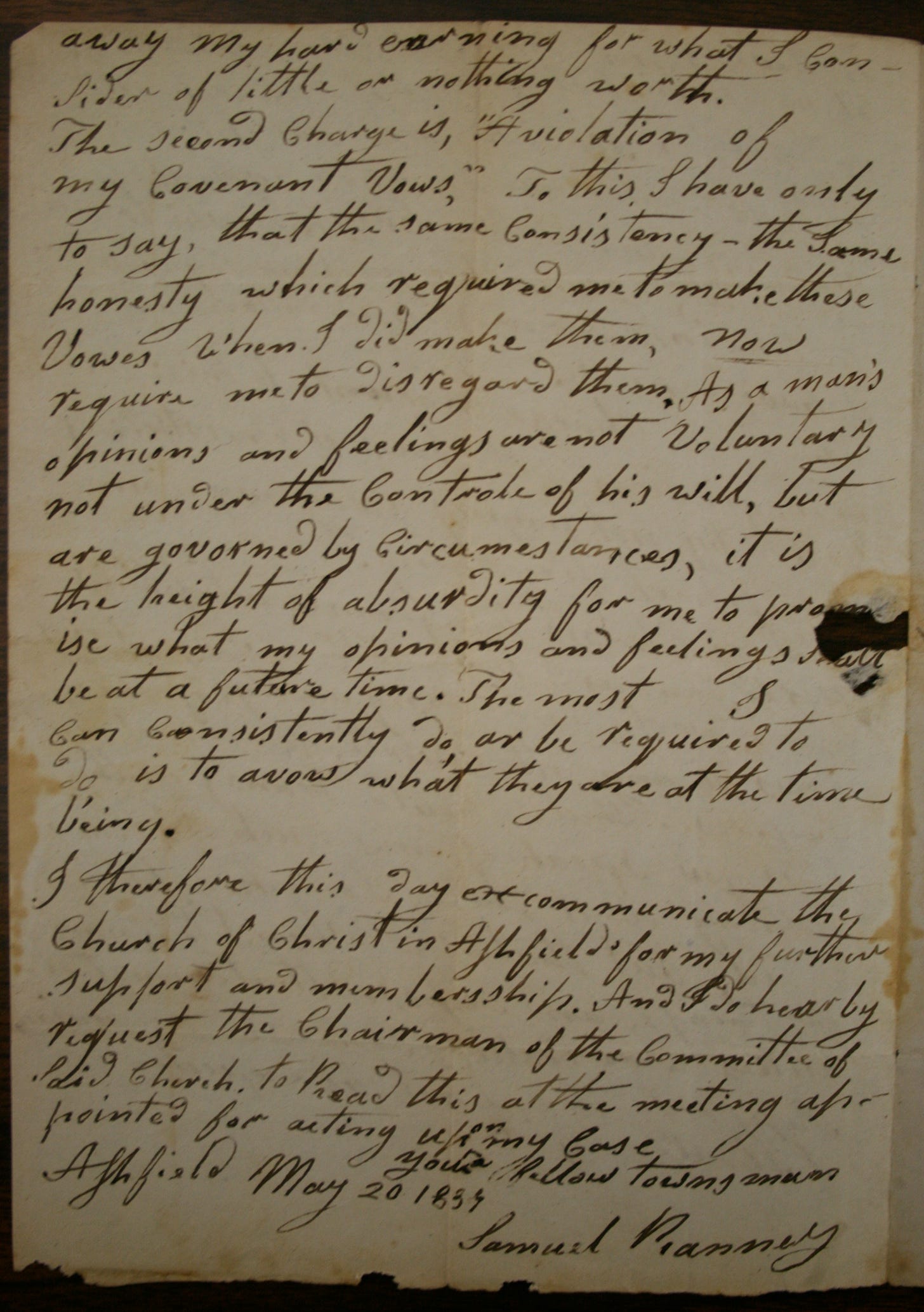

My interest in these interesting characters is genuine. I was absolutely thrilled when I discovered in a file folder in western Massachusetts, an 1834 letter from a farmer to his church community, embracing materialism and preemptively excommunicating the congregation. I wondered, “Who was this man?” Well, it turns out he was Samuel Ranney, the farmer who brought peppermint cultivation and peppermint oil distilling to Ashfield. Ranney ignited a rural industry that enriched his town – and when he left in 1835 he took the peppermint business with him to western New York. Ashfield’s fortunes continued to depend largely on peppermint oil purchased by Ranney’s nephew Henry for resale by an army of essence peddlers, but the personal story of Samuel’s rejection of authority and dogma was central in shaping the town’s history.

(Samuel Ranney’s letter to the Ashfield Congregational Church, May 20, 1834)

In western New York, brothers Hiram and Leman Hotchkiss sold competing brands of peppermint oil and ran competing banks at precisely the moment the government of Abraham Lincoln began eliminating state banking. They fought with each other over credit and over the complex obligations of family business at a time when the burnt-over district was experiencing a new association of morality with business ethics. Later in Michigan, capitalist entrepreneur Albert M. Todd competed his way to a dominant position in the peppermint oil business while at the same time promoting socialist causes such as municipal ownership and nationalizing railroads. In each case, the men who became known as peppermint kings did something unexpected; their characters contained elements more complicated than a simple account of their business successes would suggest.

In the winter 2006 issue of the Journal of the Early American Republic, historians Martin Bruegel and Naomi R. Lamoreaux conducted an argument on the merits of what Bruegel called Microhistory. Although the main thrust of the disagreement surrounded political economy, Bruegel contended that “large-scale, macrohistorical developments take extraordinarily complex shapes ‘on the ground’”, producing explanatory theories containing “a bias towards flattening out the peculiarities of the past” (quoting Kenneth Arrow, “The Social Relations of Farming in the Early American Republic: A Microhistorical Approach” Journal of the Early Republic 26:4 (Winter, 2006), 526). Bruegel argued for a new, “abstract approach to an actor-centered mode of retrieving history in which historical subjects seek out chances, confront limits, endow constraints with significance, and transform their world by engaging it” (527). Lamoreaux called this approach “antiquarianism” and suggested that economic historians “do not see why making an analysis more complicated should necessarily be considered a good thing” (“Rethinking Microhistory: A Comment”, 556).

Lamoreaux compared the story-telling activities of historians to the model-building of economists, calling the results “analytic narratives” (after Bates et. al., 558). She depicted historical change as driven by “shocks” and claimed such turning-points were “unlikely to be induced by the actions of people who are relatively powerless.” In that case, she asked, “What is the role of history written ‘on the ground’?” (559)

The answer to that question, in my opinion, is that historical subjects are complicated and multifaceted. No one is equally competent, or powerful, or correct across the entire range of their interests and activities (consider the effect of expecting uniform brilliance in all aspects of a person’s life on our current difficulties reconciling the contradictions in characters like America’s founding generation). The “shock” that led to peppermint oil production abruptly ending in Ashfield, Massachusetts, was not in a part of Samuel Ranney’s life where he was a powerful leader. It was in a strange interaction, very peripheral to the story of Ranney as a peppermint king, in which he would have been expected to knuckle under to church authority, just as several of his neighbors had done. Had I not been reading the archival letters with an open mind, following the evidence rather than trying to impose an explanatory model in which agency springs from power, I would never have discovered why 1835 was the last year peppermint was grown and oil distilled in Ashfield.

Perhaps a part of my commitment to approaching history through complex, fascinating characters comes from a slightly perverse contrarianism. In a 2001 article titled “Historians Who Love Too Much”, Jill Lepore made the comparison, “Microhistory is about ideas, and the characters in them are representative. Biography is about people, and the ideas in them are representative” (“Historians Who Love Too Much: Reflections on Microhistory and Biography”, The Journal of American History 88:1 (June, 2001), 133). But individual people are central in both. Lepore observed that “A striking figure in several microhistories is a character who legitimately evaluates, investigates, and, often, judges the subject from a rather lofty distance” (original emphasis, 139). My desire to tell stories of the past and argue historical interpretations through interesting characters may be in their ability to stand not at a “lofty distance”, but perhaps a bit apart from their moment; allowing them to offer a slightly different viewpoint on a scene we might otherwise take for granted and believe we understand. I think each of the characters I followed in Peppermint Kings was this type of outsider, and I’ll be looking for similar characters in my next story about the lumber barons and labor organizers of the great northern pine forest.