Exclusion of Heretics (1637)

None should be received to inhabit within this Jurisdiction but such as should be allowed by some of the Magistrates. It is to be considered first, what is the essential form of a commonwealth or body politic such as this is, which I conceive to be this: the consent of a certain company of people to cohabit together under one government for their mutual safety and welfare. In this description all these things do concur to the wellbeing of such a body: 1. Persons, 2. Place, 3. Consent, 4. Government or Order, 5. Welfare.

It is clearly agreed by all that the care of safety and welfare was the original cause or occasion of commonwealths and of many families subjecting themselves to rulers and laws. For no man has lawful power over another but by birth or consent. So likewise, by the law of propriety, no man can have just interest in that which belongs to another without his consent.

From the premises will arise these conclusions.

No commonwealth can be founded but by free consent.

The persons so incorporating have a public and relative interest each in other and in the place of their co-habitation and goods and laws etc. And in all the means of their welfare so as none other can claim privilege with them but by free consent.

The nature of such an incorporation ties every member thereof to seek out and entertain all means that may conduce to the welfare of the body and to keep off whatsoever does appear to tend to their damage.

The welfare of the whole is to be put to apparent hazard for the advantage of any particular members.

From these conclusions I thus reason.

If we here be a corporation established by free consent, if the place of our cohabitation be our own, then no man has right to come into us etc. without our consent.

If no man has right to our lands, our government privileges etc., but by our consent, then it is reason we should take notice of before we confer any such upon them.

If we are bound to keep off whatsoever appears to tend to our ruin or damage, then we may lawfully refuse to receive such whose dispositions suit not with ours and whose society (we know) will be hurtful to us. And therefore it is lawful to take knowledge of all men before we receive them.

The churches take liberty (as lawfully they may) to receive or reject at their discretion; yea particular towns make orders to the like effect. Why then should the commonwealth be denied the like liberty and the whole more restrained than any part?

If it be sin in us to deny some men place etc. amongst us, then it is because of some right they have to this place etc. for to deny a man that which he hath no right unto is neither sin nor injury.

If strangers have right to our houses or lands etc., then it is either of justice or of mercy. If of justice let them plead it, and we shall know what to answer. But if it be only in way of mercy or by the rule of hospitality etc., then I answer first a man is not a fit object of mercy except he be in misery. Second, we are not bound to exercise mercy to others to the mine [detriment] of ourselves. Third, there are few that stand in need of mercy at their first coming hither. As for hospitality, that rule does not bind further than for some present occasion, not for continual residence.

A family is a little commonwealth and a commonwealth is a great family. Now as a family is not bound to entertain all comers (otherwise than by way of hospitality) no more is a commonwealth.

It is a general received rule, turpius ejicitur quam non admittitur hospes [a quote from Ovid], it is worse to receive a man whom we must cast out again than to deny him admittance.

The rule of the Apostle, John 2.10 is, that such as come and bring not the true doctrine with them should not be received [in]to [a] house and by the same reason not into the commonwealth.

Seeing it must be granted that there may come such persons (suppose Jesuits etc.) which by consent of all ought to be rejected, it will follow that this law is no other but just and needful. And if any should be rejected that ought to be received, that is not to be imputed to the law but to those who are betrusted [entrusted] with the execution of it. And herein is to be considered what the intent of the law is and by consequence, by what rule they are to walk who are betrusted with the keeping of it. The intent of the law is to preserve the welfare of the body. And for this end to have none received into any fellowship with it who are likely to disturb the same, and this intent (I am sure) is lawful and good. Now then, if such to whom the keeping of this law is committed be persuaded in their judgments that such a man is likely to disturb and hinder the public weale [wellbeing], but some others who are not in the same trust judge otherwise, yet they are to follow their own judgments rather than the judgments of others who are not alike interested. As in trial of an offender by jury, the twelve men are satisfied in their consciences upon the evidence given that the party deserves death. But there are 20 or 40 standers by who conceive otherwise, yet is the jury bound to condemn him according to their own consciences and not to acquit him upon the different opinion of other men except [if] their reasons can convince them of the error of their consciences.

If it be objected that some profane persons are received and others who are religious are rejected, I answer first, it is not known that any such thing has as yet fallen out. Second, such a practice may be justifiable as the case may be, for younger persons (even profane ones) may be of less danger to the common weale (and to the churches also) than some older persons though professors of religion. One that is of large parts and confirmed in some erroneous way is likely to do more harm to church and commonwealth and is of less hope to be reclaimed than ten profane persons who have not yet become hardened in the contempt of the means of grace.

Lastly, whereas it is objected that by this law we reject good christians and so consequently Christ himself, I answer first, it is not known that any christian man has been rejected. Second, a man that is a true christian may be denied residence among us, in some cases, for such opinions (though being maintained in simple ignorance, they might stand with a state of grace yet) they may be so dangerous to the public weale in many respects as it would be our sin and unfaithfulness to receive such among us, except it were for trial of their reformation. I would demand then in the case in question, whereas it is said that this law was made of purpose to keep away such as are of Mr. Wheelwright’s judgment (admit it were so which yet I cannot confess), where is the evil of it? If we conceive and find by sad experience that his opinions are such as by his own profession cannot stand with external peace, may we not provide for our peace by keeping of such as would strengthen him and infect others with such dangerous tenets? And if we find his opinions such as will cause divisions and make people look at their magistrates, ministers, and brethren as enemies; were it not sin and unfaithfulness in us to receive more of those opinions which we already find the evil fruit of? Nay, why do not those who now complain join with us in keeping out of such, as well as formerly they did in expelling Mr. [Roger] Williams for the like, though less dangerous? Where this change of their judgments should arise I leave them to themselves to examine and I earnestly entreat them so to do. And for this law let the equally minded judge what evil they find in it, or in the practice of those who are betrusted with the execution of it.

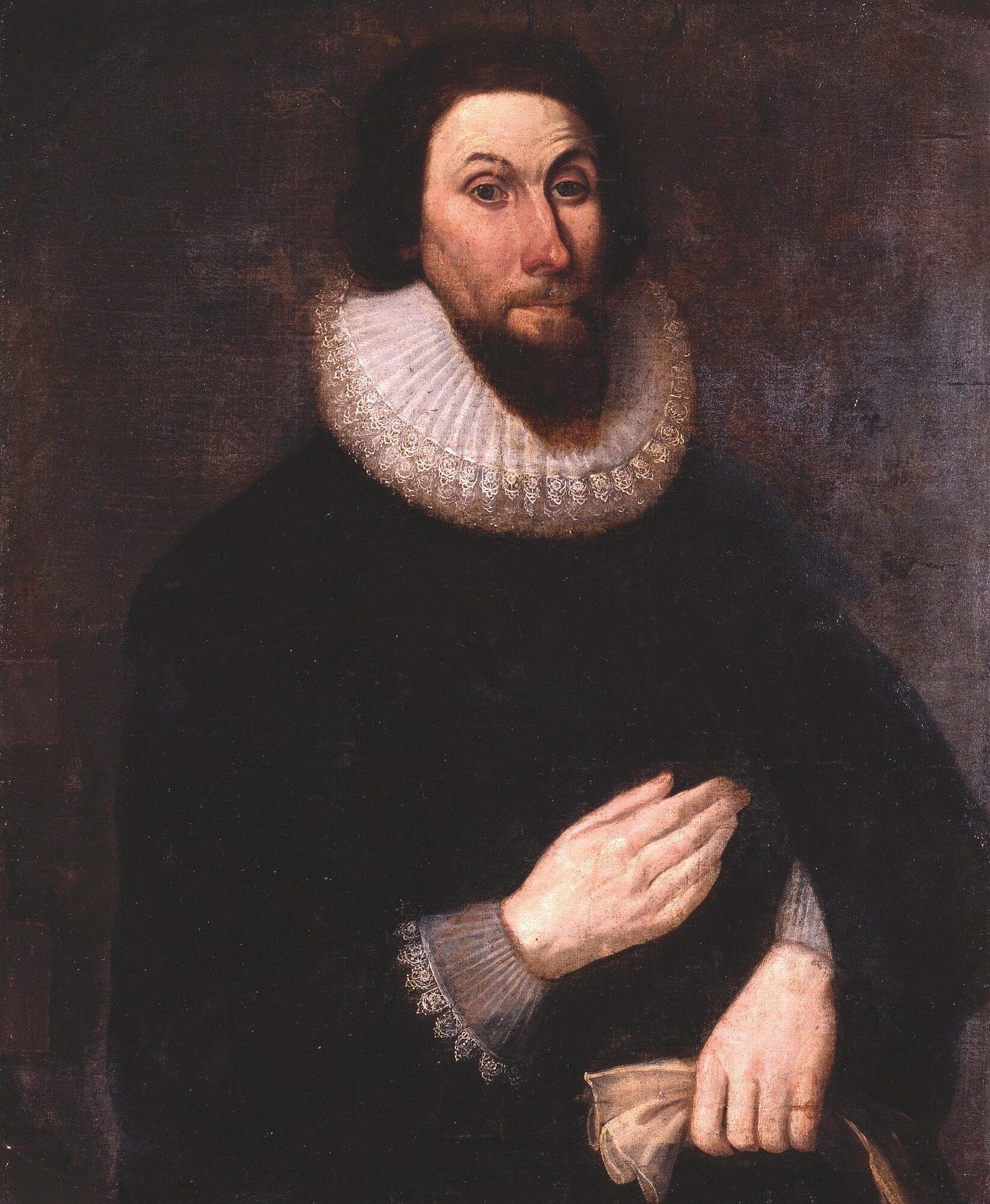

Source: "A Declaration in Defense of an Order of Court Made in May, 1637", by John Winthrop in Hutchinson Papers (1769), 67–71. https://www.masshist.org/publications/winthrop/index.php/view/PWF03d335