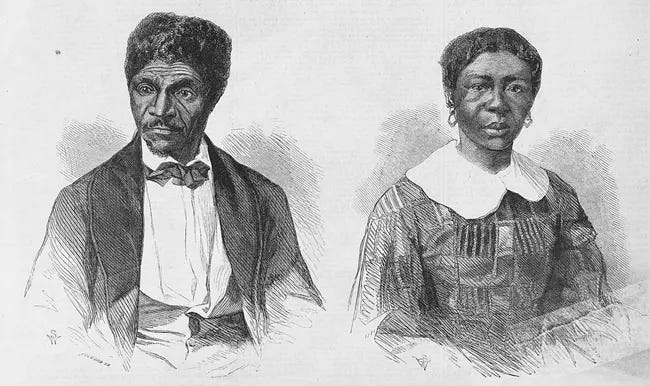

Dred and Harriet Scott

The power of the Court is judicial — so declared in the Constitution. And so held in theory, if not in practice. It is limited to cases "in law and equity" and though sometimes encroaching upon political subjects, it is without right, without authority, and without the means of enforcing its decisions. It can issue no mandamus to Congress or the people, nor punish them for disregarding its decisions or even attacking them. Far from being bound by their decisions, Congress may proceed criminally against the judges for making them, when deemed criminally wrong — one house impeach and the other try, as done in the famous case of Judge Chase.

In assuming to decide these questions (Constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise and the self-extension of the Constitution to Territories) it is believed the Court committed two great errors. First in the assumption to try such questions; secondly in deciding them as they did. And it is certain that the decisions are contrary to the uniform action of all the departments of the government — one of them for thirty-six years and the other for seventy years. And in their effects upon each are equivalent to an alteration of the Constitution by inserting new clauses in it, which could not have been put in it at the time that instrument was made, nor at any time since, nor now.

The Missouri Compromise act was a "political enactment" made by the political power, for reasons founded in national policy, enlarged and liberal, of which it was the proper judge. And which was not to be reversed afterwards by judicial interpretation of words and phrases.

Doubtless the Court was actuated by the most laudable motives in undertaking, while settling an individual controversy, to pass from the private rights of an individual to the public rights of the whole body of the people. And in endeavoring to settle by a judicial decision, a political question which engrosses and distracts the country. But the undertaking was beyond its competency, both legally and potentially [in terms of power].

It had no right to decide — no means to enforce the decision — no machinery to carry it into effect — no penalties of fines or jails to enforce it. And the event has corresponded with these inabilities. Far from settling the question, the opinion itself has become a new question, more virulent than the former! Has become the very watchword of parties! Has gone into party creeds and platforms — bringing the Court itself into the political field — and condemning all future appointments of federal judges (and the elections of those who make the appointments, and of those who can multiply judges by creating new districts and circuits) to the test of these decisions. This being the case and the evil now actually upon us, there is no resource but to face it — to face this new question — examine its foundations — show its errors and rely upon reason and intelligence to work out a safe deliverance for the country.

Repulsing jurisdiction of the original case and dismissing it for want of right to try it, there would certainly be a difficulty in getting at its merits — at the merits of the dismissed case itself. And certainly, still greater difficulty in getting at the merits of two great political questions which lie so far beyond it. The Court evidently felt this difficulty and worked sedulously to surmount it — sedulously at building the bridge, long and slender — upon which the majority of the judges crossed the wide and deep gulf which separated the personal rights of Dred Scott and his family from the political institutions and the political rights of the whole body of the American people.

In the acquisition of Louisiana came the first new territory to the United States and over it Congress exercised the same power that it had done over the original territory. It saw no difference between the old and new, as the Court has done, and governed both, independently of the Constitution and incompatibly with it and by virtue of the same right — Sovereignty and Proprietorship! The right converted into a duty, and only limited by the terms of the grant in each case.

As early as November 28th, Mr. Breckenridge, always a coadjutor [assistant] of Mr. Jefferson, submitted a resolution in the Senate to raise a committee to prepare a form of government for Louisiana. This bill contains three provisions on the subject of slaves: 1. That no one shall be imported into the Territory from foreign parts. 2. That no one shall be carried into it who had been imported into the United States since the first day of May, 1798. 3. That no one shall be carried into it except by the owner and for his own use as a settler. The penalty in every instance being a fine upon the violator of the law and freedom to the slave.

These three prohibitions certainly amount to legislating upon slavery in a Territory, and that a new Territory, acquired since the formation of the Constitution, and without the aid of compacts with any State. The Supreme Court makes a great difference between these two classes of territories and a corresponding difference in the power of Congress with respect to them, and to the prejudice of the new Territory. The Congress of 1803-4 did not see this difference and acting upon a sense of plenary authority, it extended the ordinance across the Mississippi — sent the governor and judges of Indiana (for Indiana had then become a Territory) — sent this governor (William Henry Harrison) and the three Indiana judges across the Mississippi river to administer the ordinance of '87 in that upper half of Louisiana.

It was at the session of 1818-19 that the Missouri Territory applied through her Territorial Legislature for an Act of Congress to enable her to hold a convention for the formation of a State Constitution, preparatory to the formal application for admission into the Union. The bill had been perfected, its details adjusted, and was upon its last reading when a motion was made by Mr. James Tallmadge of New York to impose a restriction on the State in relation to slavery, to restrain her from the future admission of slavery within her borders. The eventful question was called and resulted 134 for the compromise to 42 against it — a majority of three to one and eight over. Such a vote was a real compromise! A surrender on the part of the restrictionists, of strong feeling to a sense of duty to the country! A settlement of a distracting territorial question upon the basis of mutual concession and according to the principles of the ordinance of 1787. Such a measure may appear on the statute book as a mere act of Congress and lawyers may plead its repealability. But to those who were contemporary with the event and saw the sacrifice of feeling or prejudice which was made and the loss of popularity incurred, and how great was the danger of the country from which it saved us, it becomes a national compact founded on considerations higher than money and which good faith and the harmony and stability of the Union deserved to be cherished next after the Constitution.

Of the 42 who voted against the compromise, there was not one who stated a constitutional objection. All that stated reasons for their votes, gave those of expediency — among others that it was an unequal division, which was true but the fault of the South. For while contending for their share in Louisiana, they were giving away nearly all below 36° 30' to the King of Spain. There being no tie, the speaker (Mr. Clay) could not vote. But his exertions were as zealous and active in support of it, as indispensable to the pacification of the country.

From Congress the bill went to the President for his approval, and there it underwent a scrutiny which brought out the sense both of the President and his cabinet upon the precise point which has received the condemnation of the Supreme Court, and exactly contrary to the Court's decision. There was a word in the restrictive clause which, taken by itself and without reference to its context, might be construed as extending the slavery prohibition beyond the territorial condition of the country to which it attached — might be understood to extend it to the State form. It was the word "forever." Mr. Monroe took the opinion of his cabinet upon the import of this word, dividing his inquiry into two questions — whether the word would apply the restriction to Territories after they became States? And whether Congress had a right to impose the restriction upon a Territory? Upon these two questions, the opinion of the cabinet was unanimous. Negatively on the first; affirmatively, on the other.

Source: Thomas H. Benton, Historical and Legal Examination . . . of the Decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in the Dred Scott Case (1857), 4-96. https://archive.org/details/americanhistoryt00ivunse/page/132/mode/2up