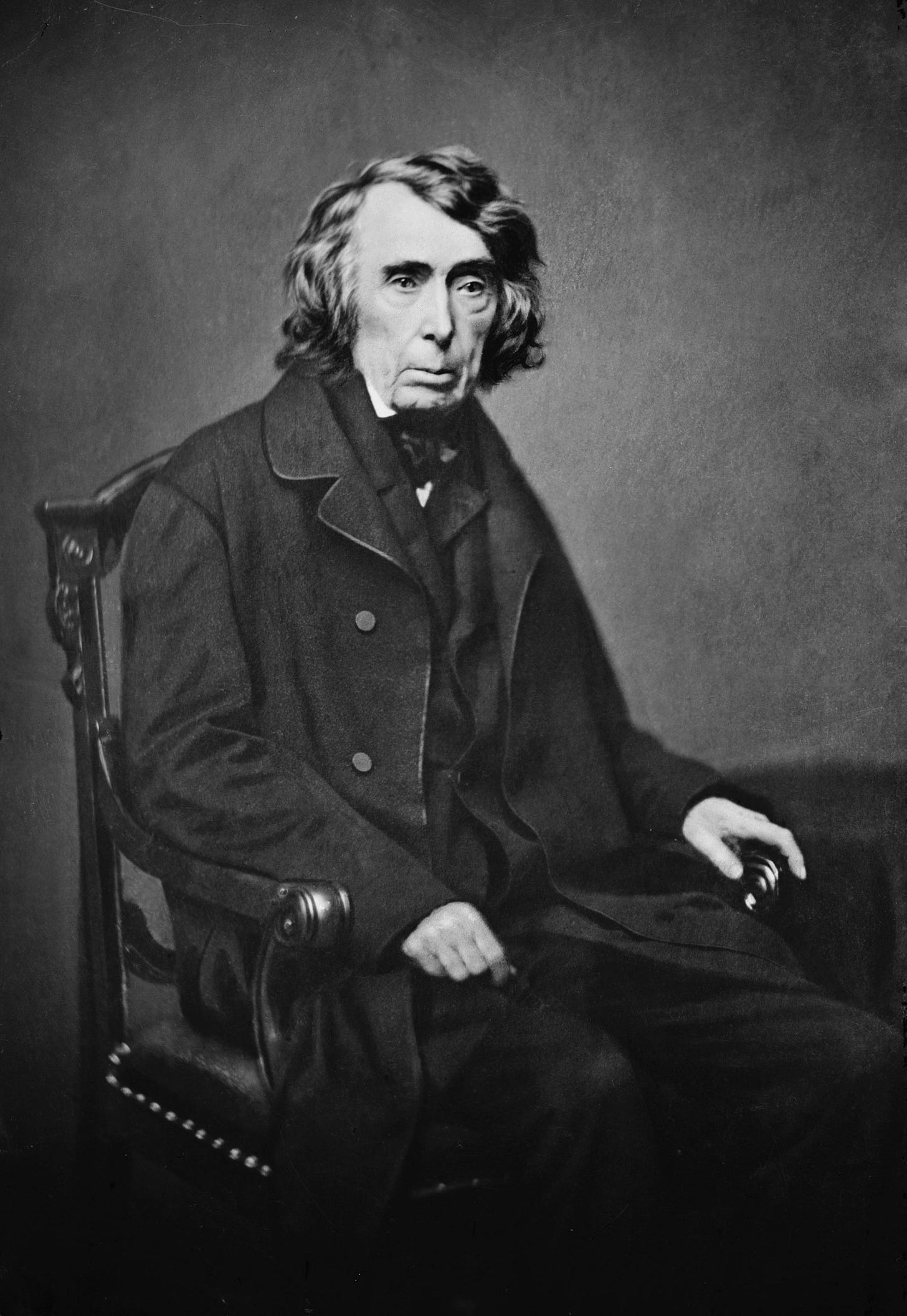

Roger Brooke Taney ca. 1858

The question is simply this: Can a negro whose ancestors were imported into this country and sold as slaves become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States and as such become entitled to all the rights and privileges and immunities guaranteed by that instrument to the citizen?

It is difficult at this day to realize the state of public opinion in relation to that unfortunate race, which prevailed in the civilized and enlightened portions of the world at the time of the Declaration of Independence and when the Constitution of the United States was framed and adopted. But the public history of every European nation displays it in a manner too plain to be mistaken. They had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations. And so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit. He was bought and sold and treated as an ordinary article of merchandise and trade, whenever a profit could be made by it. This opinion was at that time fixed and universal in the civilized portion of the white race. It was regarded as an axiom in morals as well as in politics, which no one thought of disputing or supposed to be open to dispute. And men in every grade and position in society daily and habitually acted upon it in their private pursuits as well as in matters of public concern, without doubting for a moment the correctness of this opinion.

The opinion thus entertained and acted upon in England was naturally impressed upon the colonies they founded on this side of the Atlantic. And accordingly, a negro of the African race was regarded by them as an article of property and held and bought and sold as such, in every one of the thirteen colonies which united in the Declaration of Independence and afterwards formed the Constitution of the United States. The slaves were more or less numerous in the different colonies, as slave labor was found more or less profitable. But no one seems to have doubted the correctness of the prevailing opinion of the time.

The language of the declaration of independence is equally conclusive. "We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among them is life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights, governments are instituted, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed." The general words above quoted would seem to embrace the whole human family and if they were used in a similar instrument at this day would be so understood. But it is too clear for dispute, that the enslaved African race were not intended to be included and formed no part of the people who framed and adopted this declaration. For if the language, as understood in that day, would embrace them, the conduct of the distinguished men who framed the declaration of independence would have been utterly and flagrantly inconsistent with the principles they asserted and instead of the sympathy of mankind to which they so confidently appealed, they would have deserved and received universal rebuke and reprobation.

But there are two clauses in the Constitution which point directly and specifically to the negro race as a separate class of persons and show clearly that they were not regarded as a portion of the people or citizens of the government then formed. One of these clauses reserves to each of the thirteen States the right to import slaves until the year 1808, if it thinks proper. And by the other provision the States pledge themselves to each other to maintain the right of property of the master by delivering up to him any slave who may have escaped from his service and be found within their respective territories. These two provisions show conclusively that neither the description of persons therein referred to nor their descendants were embraced in any of the other provisions of the Constitution. For certainly these two clauses were not intended to confer on them or their posterity the blessings of liberty or any of the personal rights so carefully provided for the citizen.

The only two provisions which point to them and include them, treat them as property and make it the duty of the government to protect it. No other power, in relation to this race, is to be found in the Constitution. And as it is a government of special, delegated, powers, no authority beyond these two provisions can be constitutionally exercised. The government of the United States had no right to interfere for any other purpose but that of protecting the rights of the owner, leaving it altogether with the several States to deal with this race, whether emancipated or not, as each State may think justice, humanity, and the interests and safety of society require. The States evidently intended to reserve this power exclusively to themselves.

And upon a full and careful consideration of the subject, the court is of opinion that, upon the facts stated in the plea in abatement, Dred Scott was not a citizen of Missouri within the meaning of the Constitution of the United States and not entitled as such to sue in its courts.

The act of Congress upon which the plaintiff relies, declares that slavery and involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime, shall be forever prohibited in all that part of the territory ceded by France under the name of Louisiana, which lies north of thirty-six degrees thirty minutes north latitude and not included within the limits of Missouri. And the difficulty which meets us at the threshold of this part of the inquiry is whether Congress was authorized to pass this law under any of the powers granted to it by the Constitution. For if the authority is not given by that instrument, it is the duTy of this court to declare it void and inoperative and incapable of conferring freedom upon anyone who is held as a slave under the laws of any one of the States.

The counsel for the plaintiff has laid much stress upon that article in the Constitution which confers on congress the power "to dispose of and make all needful rules and regulations respecting the territory or other property belonging to the United States". But in the judgment of the court, that provision has no bearing on the present controversy and the power there given, whatever it may be, is confined and was intended to be confined to the territory which at that time belonged to or was claimed by the United States and was within their boundaries as settled by the treaty with Great Britain, and can have no influence upon a territory afterwards acquired from a foreign government. It was a special provision for a known and particular territory and to meet a present emergency, and nothing more.

If the Constitution recognizes the right of property of the master in a slave and makes no distinction between that description of property and other property owned by a citizen, no tribunal acting under the authority of the United States, whether it be legislative, executive, or judicial has a right to draw such a distinction or deny to it the benefit of the provisions and guarantees which have been provided for the protection of private property against the encroachments of the government. Now, as we have already said in an earlier part of this opinion, upon a different point, the right of property in a slave is distinctly and expressly affirmed in the Constitution. This is done in plain words — too plain to be misunderstood. And no word can be found in the Constitution which gives congress a greater power over slave property or which entitles property of that kind to less protection than property of any other description. The only power conferred is the power coupled with the duty of guarding and protecting the owner in his rights.

Upon these considerations, it is the opinion of the court that the act of congress which prohibited a citizen from holding and owning property of this kind in the territory of the United States north of the line therein mentioned is not warranted by the constitution and is therefore void. And that neither Dred Scott himself nor any of his family were made free by being carried into this territory, even if they had been carried there by the owner with the intention of becoming a permanent resident.

Source: Dred Scott v. Sandford, in Samuel F. Miller, Reports of Decisions in the Supreme Court of the United States (1875), II, 6-56. https://archive.org/details/americanhistoryt00ivunse/page/126/mode/2up

The Dred Scott Decision a.k.a. Roger Taney's Big Mistake.