Defects of Confederation

Articles of Confederation

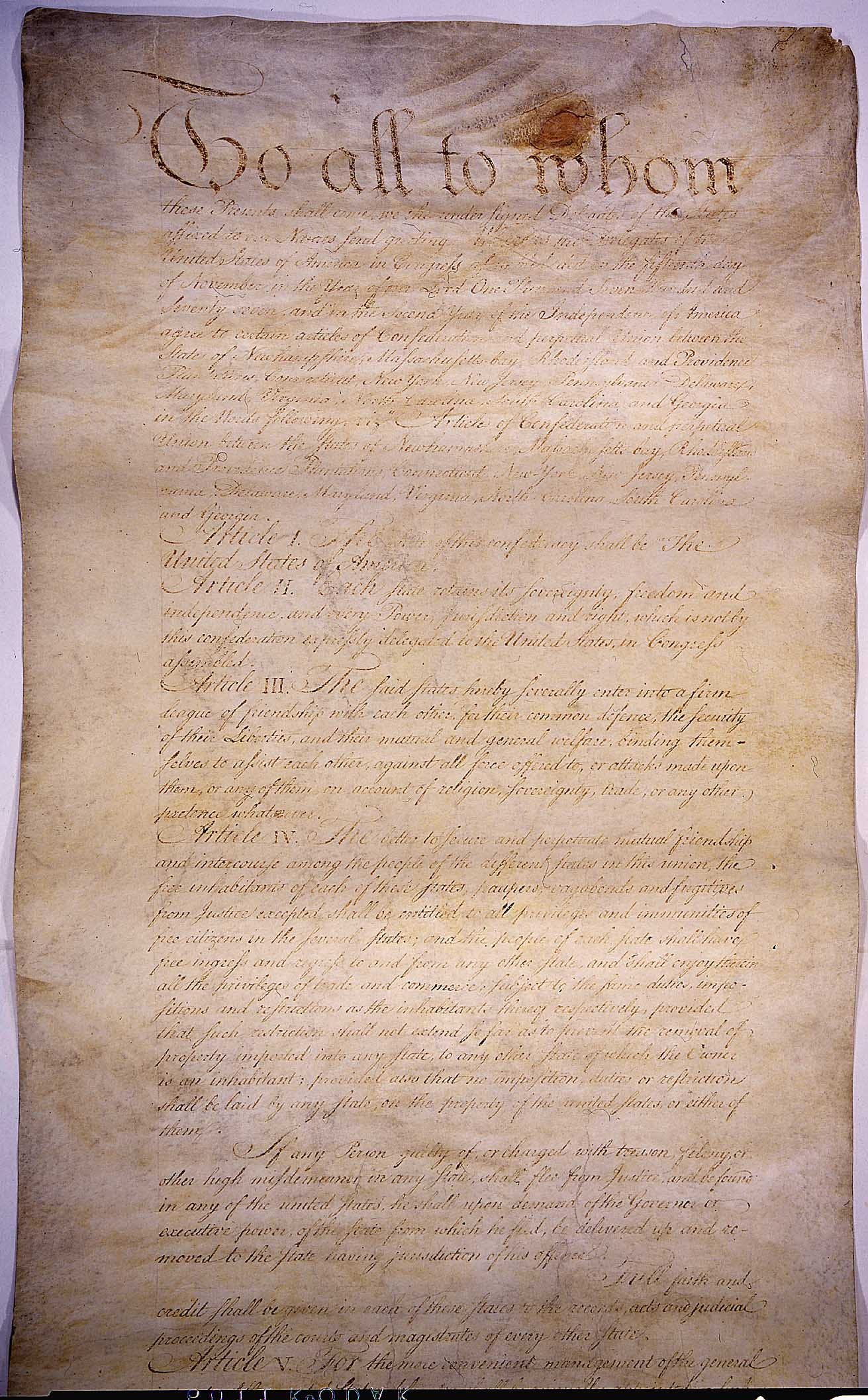

No sooner was peace restored by the definitive treaty and the British troops withdrawn from the country, than the United States began to experience the defects of their general government. While an enemy was in the country, fear which had first impelled the colonists to associate in mutual defense continued to operate as a band of political union. Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union had been framed in Congress and submitted to the consideration of the states in the year 1778. These articles however were framed during the rage of war when a principle of common safety supplied the place of a coercive power in government. Hence the numerous defects of the confederation.

On the conclusion of peace, these defects began to be felt. Each state assumed the right of disputing the propriety of the resolutions of congress and the interest of an individual state was placed in opposition to the common interest of the union. Jealousy of power had been universally spread among the people of the United States. The destruction of the old forms of governments and the licentiousness of war had, in a great measure, broken their habits of obedience.

This weakness of the federal government, in conjunction with the flood of certificates or public securities which Congress could neither fund nor pay, occasioned them to depreciate to a very inconsiderable value. Pennsylvania indeed made provision for paying the interest of her debts both state and federal, assuming her supposed proportion of the continental debt, and giving the creditors her own state notes in exchange for those of the United States. The resources of that state are immense but she has not been able to make punctual payments, even in a depreciated paper currency. Massachusetts in her zeal to comply fully with the requisitions of Congress and satisfy the demands of her own creditors, laid a heavy tax upon the people. This was the immediate cause of the rebellion in that state in 1786. But the loss of public credit, popular disturbances, and insurrections were not the only evils which were generated by the peculiar circumstances of the times.

Industry likewise had suffered by the flood of money which had deluged the states. The prices of produce had risen in proportion to the quantity of money in circulation and the demand for the commodities of the country. The state of Virginia had too much wisdom to emit bills but tolerated a practice among the inhabitants of cutting dollars and smaller pieces of silver in order to prevent it from leaving the state. This pernicious practice prevailed also in Georgia. New Jersey is situated between two of the largest commercial towns in America [New York and Philadelphia] and consequently drained of specie. This state also emitted a large sum in bills of credit which served to pay the interest of the public debt. But the currency depreciated, as in other states.

Rhode Island exhibits a melancholy proof of that licentiousness and anarchy which always follows a relaxation of the moral principles. In a rage for supplying the state with money and filling every man's pocket without obliging him to earn it by his diligence, the legislature passed an act for making one hundred thousand pounds in bills. The merchants in Newport and Providence opposed the act with firmness. But the state was governed by faction. During the cry for paper money, a number of boisterous ignorant men were elected into the legislature from the smaller towns in the state. Finding themselves united with a majority in opinion, they formed and executed any plan their inclination suggested. They opposed every measure that was agreeable to the mercantile interest. They not only made bad laws to suit their own wicked purposes but appointed their own corrupt creatures to fill the judicial and executive departments. Their money depreciated sufficiently to answer all their vile purposes in the discharge of debts. Business almost totally ceased, all confidence was lost, the state was thrown into confusion at home and was execrated abroad.

Massachusetts Bay had the good fortune amidst her political calamities to prevent an emission of bills of credit. New Hampshire made no paper but in the distresses which followed her loss of business after the war the legislature made horses, lumber and most articles of produce a legal tender in the fulfillment of contracts. The legislature of New York, a state that had the least necessity and apology for making paper money as her commercial advantages always furnish her with specie sufficient for a medium, issued a large sum in bills of credit which support their value better than the currency of any other state. Still the paper has raised the value of specie, which is always in demand for exportation and this difference of exchange between paper and specie exposes commerce to most of the inconveniences resulting from a depreciated medium.

While the states were thus endeavoring to repair the loss of specie by empty promises and to support their business by shadows rather than by reality, the British ministry formed some commercial regulations that deprived them of the profits of their trade to the West Indies and to Great Britain. Heavy duties were laid upon such articles as were remitted to the London merchants for their goods and such were the duties upon American bottoms [cargoes], that the states were almost wholly deprived of the carrying trade. A prohibition was laid upon the produce of the United States shipped to the English West India Islands in American built vessels and in those manned by American seamen. These restrictions fell heavy upon the eastern states which depended much upon ship-building for the support of their trade and they materially injured the business of the other states.

Without a union that was able to form and execute a general system of commercial regulations, some of the states attempted to impose restraints upon the British trade that should indemnify the merchant for the losses he had suffered or induce the British ministry to enter into a commercial treaty and relax the rigor of their navigation laws. These measures however produced nothing but mischief. The states did not act in concert and the restraints laid on the trade of one state operated to throw the business into the hands of its neighbor. Massachusetts in her zeal to counteract the effect of the English navigation laws laid enormous duties upon British goods imported into that state. But the other states did not adopt a similar measure and the loss of business soon obliged that state to repeal or suspend the law. Thus when Pennsylvania laid heavy duties on British goods, Delaware and New Jersey made a number of free ports to encourage the landing of goods within the limits of those states. And the duties in Pennsylvania served no purpose but to create smuggling.

Thus divided, the states began to feel their weakness. Most of the legislatures had neglected to comply with the requisitions of Congress for furnishing the federal treasury. The resolves of Congress were disregarded; the proposition for a general impost to be laid and collected by Congress was negatived first by Rhode Island and afterwards by New York. The British troops continued under pretense of a breach of treaty on the part of America to hold possession of the forts on the frontiers of the states and thus commanded the fur trade. Congress lost their respectability and the United States their credit and importance. The old confederation was essentially defective. It was destitute of almost every principle necessary to give effect to legislation. The confederation was also destitute of a sanction to its laws. When resolutions were passed in Congress, there was no power to compel obedience. It was also destitute of a guarantee for the state governments. Had one state been invaded by its neighbor, the union was not constitutionally bound to assist in repelling the invasion and supporting the constitution of the invaded state. And to crown all the defects, we may add the want of a judiciary power to define the laws of the union and to reconcile the contradictory decisions of a number of independent judicatories.

Source: Jedidiah Morse, The American Geography (1789), 113-123. https://archive.org/details/toldcontemporari03hartrich/page/130/mode/2up