Darwin vs. Birth Control

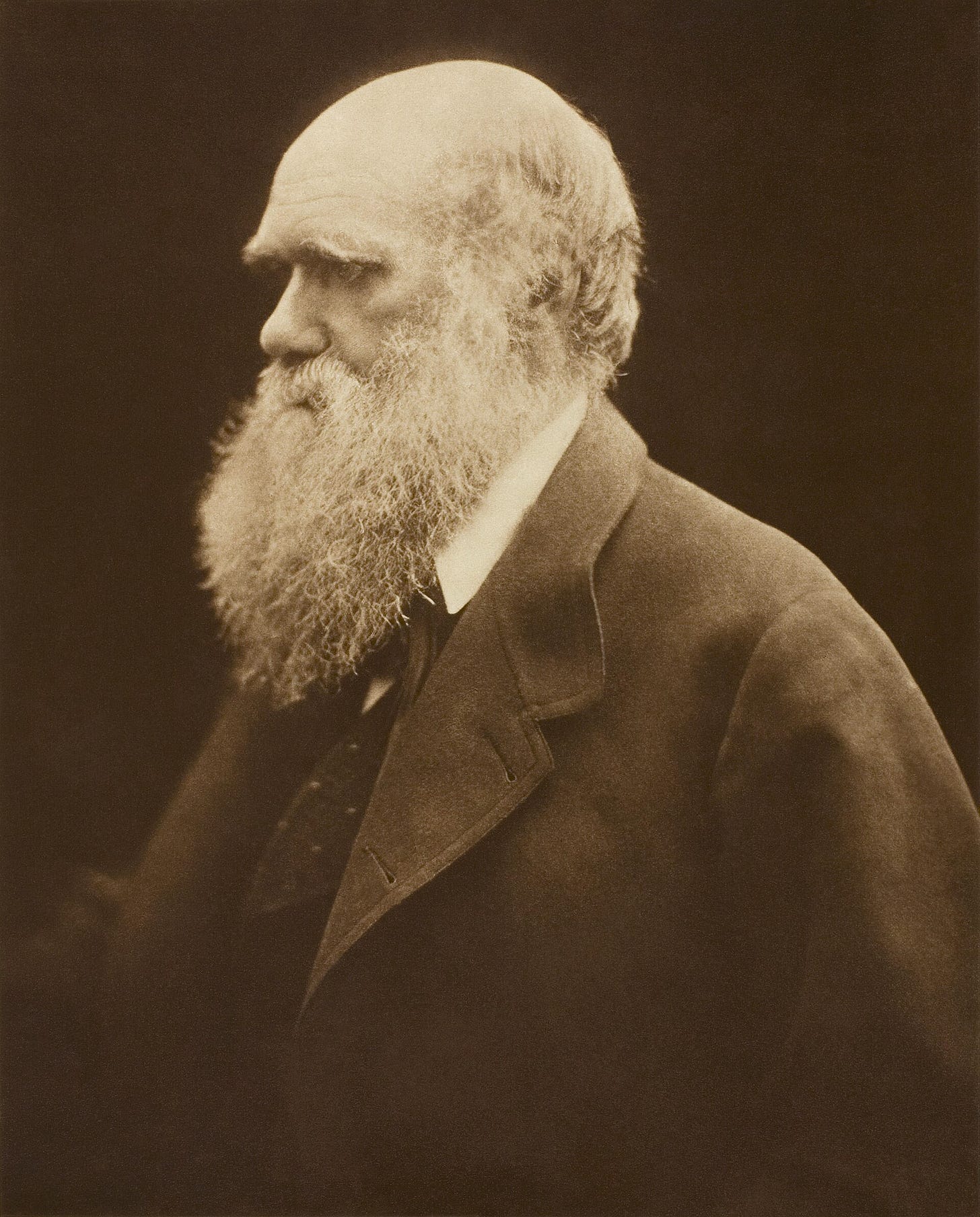

I’m beginning to unarchive my Charles Bradlaugh research from 2006-2009, possibly in preparation for a biography of Bradlaugh’s youth I’ve considered, off and on. One of the things that jumped out at me today, in addition to several great photos of young Charles, was an article written in 2007 by Sandra J. Peart and David M. Levy, called “Darwin's unpublished letter at the Bradlaugh–Besant trial: A question of divided expert judgment” (European Journal of Political Economy 24, 2008, 343-353). In it, the authors claimed that the 1877 Bradlaugh-Besant trial was really a debate between the principles of two experts: John Stuart Mill, who favored birth control, versus Charles Darwin, who opposed it. While I think it’s very interesting that Darwin opposed birth control (and why), I beg to differ. Neither of the men named was an expert on the issue at stake, but the fact they were believed to be (by some people at the time and by many now) tells us something important.

Wait a minute! Darwin opposed birth control? How could that be? And if he did, he must have had a good reason, right?

Not really. Darwin was a socially conservative member of the upper middle-class. When atheist firebrand Charles Bradlaugh, who had called for the elimination of the House of Lords and the Monarchy itself in his radical weekly, The National Reformer, wrote to Darwin, the old man was alarmed. Bradlaugh and his partner, Annie Besant, wanted the famous scientist to appear as a witness for the defense in a trial to determine whether republication of Dr. Charles Knowlton’s birth control book The Fruits of Philosophy as a six-penny pamphlet was obscene. Darwin replied to Bradlaugh that he was ill, he was planning to be out of town, and in any case, “I sh[oul]d be forced to express in court a very decided opinion in opposition to you and Mrs. Besant” (Letter, June 6, 1877)

With this denunciation, Darwin sent an explanatory excerpt from The Descent of Man, in which he basically said that birth control was a bad idea because “if the prudent avoid marriage, whilst the reckless marry, the inferior members tend to supplant the better members of society.” This would be the opposite outcome from natural selection, which Darwin believed should be allowed to operate in human populations as well as animal. In The Descent of Man, Darwin did not claim to have come to this conclusion on his own. In fact, he admitted “This subject has been ably discussed by Mr W. R. Greg, and previously by Mr Wallace and Mr Galton. Most of my remarks are taken from these three authors.” We like to hold up Darwin as a spotless exemplar and blame Herbert Spencer for all the evils of Social Darwinism. These words from Darwin’s own pen seem to challenge that belief.

After referring Bradlaugh to these second-hand ideas, Darwin went on to say he believed “such practices would in time spread to unmarried women & w[oul]d destroy chastity on which the family bond depends.” This had been a common argument against birth control since Knowlton’s first printing of The Fruits of Philosophy in 1832, and if Darwin had any familiarity with the subject, he would have been aware how thoroughly the “spreading vice” argument had been discredited, both by argument and evidence. Annie Besant had no trouble countering both Darwin’s vice and “natural selection” arguments at the trial.

In her testimony, Besant declared that the “natural selection” approach to social advancement “is only a natural check in the sense that nature is opposed to art, to science, or to men’s reason.” The authors of the 2008 article called this a “profound argument,” and it was — but it wasn’t new. It’s not even Annie Besant’s. It was developed by Charles Knowlton in the 1830s, possibly with the collaboration of Robert Dale Owen. Both Knowlton and Owen used it in their books, as in this example from 1834:

It has been said, it is best to let nature take her course. Now in the broadest sense of the word nature I say so too. In this sense there is nothing unnatural in the universe. But if we limit the sense of the word nature so as not to include what we mean by art, then is civilized life one continued warfare against nature.

The fact that Annie Besant was either aware of these long-standing arguments regarding birth control, or came up with them on her own, suggests that the name of expert has been given to the wrong persons. Darwin had at best a shallow, second-hand understanding of the issues and the stakes. If he had spent more time thinking about it or had observed the lives of working-class English families as closely as he did Galapagos wildlife, he might have come to a different conclusion than that natural selection ought to be allowed free rein, regardless of the human misery it caused. But that was his conclusion.

The London Times and the recent article’s authors said the other party in this elite debate of experts was John Stuart Mill, who had been dead for several years by the time Bradlaugh and Besant made their stand. Once again, Besant’s name-dropping was the source of the claim. But in this case I think the connection is a little more interesting. As a very young man, Mill had been arrested for passing out birth control leaflets to the poor. He was probably collaborating with Francis Place, one of the very earliest advocates of family planning and a friend of his father. Ironically, at the time this was a closely guarded secret which the Times would probably not have known. The “expertise” Mill provided to support Besant’s argument was a quotation from his Principles of Political Economy, reiterating her point about nature: “Civilisation in every one of its aspects is a struggle against the animal instincts.” Since Mill did show a lifelong (if often secret) interest in birth control, it’s fair to assume he was aware that he was walking a well-worn path with this train of thought.

So in the end, neither Charles Darwin nor John Stuart Mill really contributed original thoughts to the birth control debate surrounding the Bradlaugh-Besant trial in 1877. Neither were experts on the subject, and Darwin wasn’t even aware of what the actual experts had been saying for over a generation. That they were used by nineteenth-century Victorians to stake out political territory is interesting. That they are taken by twenty-first-century historians as the sources of important principles behind the (unimportant?) event is really a bit problematic.