William Cronon begins this chapter by claiming precedence for Chicago as a North American place where “the products of rural nature entered the urban market to become commodities” (148). He wrestles a bit with Karl Marx regarding the idea that all value comes from labor (which he mentions was not originally Marx’s idea but a carryover of classical economics), arguing that in the case of the lumber industry “Human hands and human sweat” were necessary, but a great deal of value came from appropriating the “stored sunshine” represented by wood (149). While this is true, I’m not sure if the main point is that ultimately the only thing that catalyzes biological processes is the sun. A larger point, from the human perspective, might have to do with who gets to benefit from that appropriation, and how the benefits and the work of extraction are allocated.

One point that jumped out at me in the introductory paragraphs, although Cronon didn’t focus on it, was that the remoteness of the forests from the place where the value was realized in cash helped hide not only the fact that the cash being collected was a monetization of nature’s bounty, but also made it easier to undervalue the work involved in getting the trees out of the woods and transformed into lumber. Not to mention the environmental costs and “externalities”, which I’ll return to later.

Cronon develops these introductory thoughts into a reinterpretation of Frederick Jackson Turner’s famous thesis, suggesting that the real power of the frontier was that “its abundance offered to human labor rewards incommensurate with the effort expended in achieving them” (150). This “unexploited natural abundance” was a free lunch of sorts. It was a benefit that accrued to the people who controlled the bringing of valuable natural products into markets. To some extent, the way they “earned” the benefit was by being in the right place at the right time and preventing others from participating. This isn’t to say that it was a trivial task building a giant lumber business; but I am questioning the elements that justified great fortunes. Ownership regimes are socially constructed, after all, and four hundred year-old trees are in some ways more like mineral deposits than like corn or wheat.

Frankly, the author’s claim that Chicago was preeminent in all the markets he describes sort of gets on my nerves. I deliberately used Minneapolis grain milling in my textbook chapter on centers and peripheries that was inspired by Nature’s Metropolis, for example. In the lumber industry, I suspect Chicago’s place at the center of the story depends quite a bit on the timescale you choose to consider. This is not to say that Chicago wasn’t an important center for the lumber industry. But Nathan Mears, really? Mears owned 40,000 acres of Michigan timberland. What about Weyerhäuser (barely mentioned)? What about Walker (not a word)? I guess I’ll be able to answer that question with numbers, as I dig into the data.

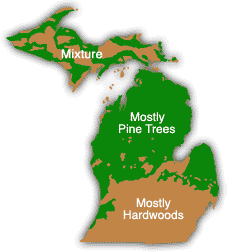

A couple of observations struck me as brilliantly obvious, and I think it’s important to credit Cronon’s mentioning them. First is the fact that Lake Michigan connects the prairie in the south with the pine forests in the north. The Mississippi River does this as well, which Cronon mentions briefly but doesn’t really explore. Second is the fact that pine is much more buoyant than hardwoods, which made it much easier to float pine timber to mills before the age of rail. The fact that “most of the timber-bearing rivers and streams of upper Michigan and northeastern Wisconsin flowed into Lake Michigan” and that steamships could push huge rafts of timber across the lake to Chicago definitely enhanced the city’s centrality in the early lumber business (153). Cronon then explores the metaphor of the typical farm, with cultivated land and a woodlot. He quotes a lumber journal editor in 1873 imagining the entire Mississippi River Valley as “a huge farm with a very small grove in the northeast corner” (154). This is “a landscape of mutual advantage”, with each region depending on the other for the products it cannot provide itself. The fact that cutting timber was winter work enhanced this sense of balance, as farmers joined logging camps after the harvest and returned to the fields after the spring thaw.

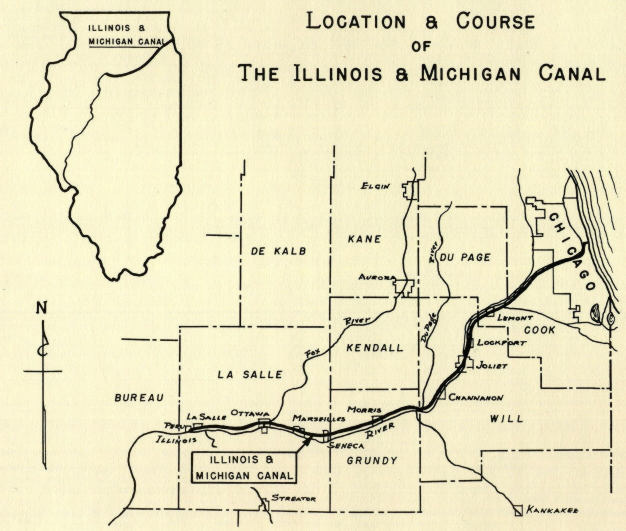

Cronon mentions that the Illinois and Michigan Canal “doubled Chicago’s lumber receipts in a single year” when it was opened in 1848. The canal connecting Lake Michigan with the Mississippi River at LaSalle-Peru was 96 miles long and 60 feet wide, with seventeen locks. Towns were planned along the canal, corresponding with the distance mules could haul barges in a day. A lot of lumber probably went to build these new communities, in addition to the wood that spread into farm country. He also mentions that during the 1830s and 40s, one of Michigan’s earliest lumber-milling districts grew up around Saginaw Bay on Lake Huron. This region was far from Chicago, and most of its lumber was shipped east to Ohio, New York, and the Erie Canal (158). But there was also a lot of cutting along the Grand River which emptied into Lake Michigan at Grand Haven. As I found when researching Yankee migrants for Peppermint Kings, New England and New York families worked winters cutting timber in the mid-1830s. George Ranney, two of his sons, and his son-in-law cut timber on the Grand River during the winter of 1836-7, before even moving to Michigan (PK p. 55).

Cronon also describes the “Boom Companies” that began in the earlier Maine and Pennsylvania lumber industries, that were established to split the costs of managing dams, holding basins, and hoists. They even controlled the flow of rivers, as Cronon describes happening in 1893 (159). I wonder if there may be a story about a lost opportunity for cooperation here? Another economic reality affecting the development of lumber businesses was their seasonality. “Throughout the fall and winter months,” Cronon says, “firms had to spend thousands of dollars on food, supplies, and wages, even thought hey could ship no lumber to market as long as Lake Michigan and the port cities were locked in ice” (167). Could these capital requirements have been met in other ways than those that emerged?

A unique element of Chicago as a lumber center, Cronon says, was the cash basis of the business. An average of three million board feet of lumber was sold daily at the cargo docks while still in the holds of ships, seven months out of the year (171). So mills could send their lumber to Chicago and get cash immediately, rather than shipping to customers in other ports who bought on credit terms. The tradeoff was that mills got lower prices in the competitive Chicago cargo market. Nine thousand of the ships arriving at Chicago’s harbor in 1872 carried lumber (172). Cronon also briefly mentions Augustine D. Taylor, a pioneer of the balloon frame construction that used the new dimensional softwood. The new technique, which allowed more people to build than the more complicated, earlier post-and-beam construction, expanded the market for lumber. “By 1860, the city’s yards were annually shipping over 220 million board feet of lumber….By 1870, the city’s lumber shipments had risen to over 580 million board feet, and by 1880, to over a billion board feet” (original emphasis, 181).

The railroads that had enabled Chicago to dominate the lumber market in the early years were also the key to the city’s decline. Mill operators who sold to Chicago middlemen resented the lack of control and low prices allowed them. Beginning in the 1870s, Cronon says, they began looking for ways to sell their lumber directly to customers. The growing rail network made it possible for mills in Muskegon and Marinette-Menominee to stop shipping their lumber to Chicago. In 1885, the Kirby-Carpenter Company closed its Chicago operation (194-5). Cronon then briefly mentions the Mississippi Valley lumber industry and Frederick Weyerhäuser, but this seems like an afterthought (196).

Finally, Cronon briefly covers the environmental cost of the industry on the region that became known as the “cutover”. As the best trees began to run out, loggers began cutting smaller-diameter trees and processing more of the wood into lumber. This resulted in lower quality planks and boards than had been produced when only the best parts of the logs were processed — although it also greatly reduced the waste. The Pehstigo Fire (1871), Hinckley Fire (1894), and Cloquet Fire (1918) probably deserve more attention, especially because the two in Minnesota are part of a later chapter of the story than that focused on Chicago. But Cronon’s point that ignoring externalities and forgetting that the wealth “created” in centers like Chicago was made “easier the farther one traveled from the north country”, is powerfully supported by a look at the cost these regions paid during the forest exploitation and in the aftermath.

Endnote: The endnotes for this chapter are a goldmine. I jumped back and forth as I was reading, highlighting sources as well as passages. Now I’m going to dig into them and read as many of the sources as I can get my hands on.

(Images: Author photo of book cover, CC-BY-SA; Illinois and Michigan Canal, public domain; Michigan tree types, unknown license)

If you liked this, you might like: