Calomel

A Conference Paper I presented while in Grad School

Calomel, “empirics,” and medical legitimacy, 1830-1850

In March 1844 Massachusetts country doctor Charles Knowlton wrote a letter to the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. He confessed that he suspected himself of infecting a new mother with Erysipelas, giving her a fatal case of Puerperal Fever. Oliver Wendell Holmes had published “The Contagiousness of Puerperal Fever” only a year earlier in the New England Quarterly Journal of Medicine and the issue was still hotly contested, so Knowlton was not only demonstrating he was up to date with the literature, he was taking a stand on a politically charged issue.[1] But he went further. Aware that his actions would be questioned by his peers, Knowlton argued:

if my treatment of the cases is to be criticized at all, let it not be done by the city practitioner, who, instead of spending most of his hours in buffeting the winds and storms 'o'er hill and dale,' as in country practice, may spend them at the bedside of the sick, acquiring practical experience—or in his study, treasuring up the experience of others; who can examine and re-examine both his patient and his library within the space of half an hour… But rather let it be criticized by the country practitioner, who knows what it is to be caught, perhaps in the night, some five or ten miles from home, at the bedside of a patient presenting urgent and alarming symptoms with which he is not practically familiar, and all this without any aid at command beyond what he may chance to have in his pockets and saddlebags. These are the circumstances that ‘try men's souls,’ and qualify country physicians to sit in judgment upon the practice of each other.[2]

Dr. Knowlton’s remarks suggest a tension between urban and rural physicians, and also point to his respect for experience as a mark of professionalism and expertise. But Charles Knowlton was a freethinker and the author of America’s first birth control manual. He had written his 1824 thesis for the medical lectures at Hanover, on the importance of anatomy. Dartmouth, like other respectable colleges, held medical lectures nearby but outside their official “walls,” and Dr. Nathan Smith, who had organized the medical programs at Dartmouth, Bowdoin, and the University of Vermont, was extensively grilled by President Timothy Dwight regarding his religious and moral orthodoxy and suspicions he was an “anatomist,” before being allowed to commence teaching at Yale.[3] On graduation from Hanover, Knowlton went directly to Worcester Massachusetts to serve three months imprisonment for stealing bodies from a local cemetery. But to what degree did Knowlton’s remarks reflect or speak for the developing profession? The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal holds a possible answer, in the form of a decade-long debate over the effectiveness and dangers of the drug Calomel. Years later, in a letter to the editors, Knowlton described the conflict between Thomsonian herbalists, whom he called Dr. Lobelia, and traditional physicians, whom he called Dr. Calomel. The conflict was between experience and authority, and the battle-lines were drawn largely on an urban-rural basis.

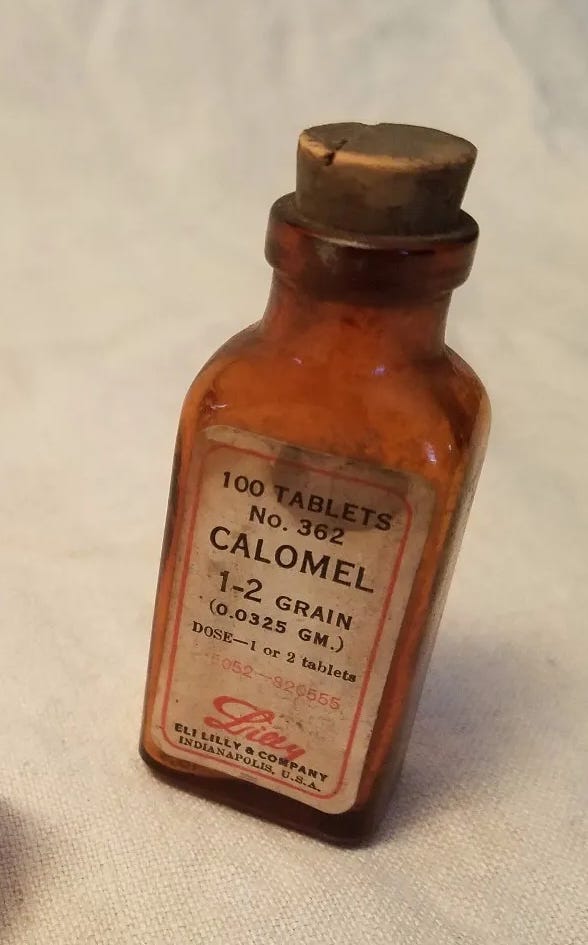

Calomel is a chloride of mercury, known since the days of the alchemists. Its use was promoted in the leading medical schools at London and Edinburgh, and eighteenth-century Americans who studied there subsequently taught Calomel’s purgative, tonic, and cathartic properties to their own students at home. Along with bleeding, Calomel became a centerpiece of Dr. Benjamin Rush’s “heroic” style of treatment and was featured in authoritative American texts.[4] Calomel became such a standard part of the American material medica that in Dartmouth’s Hanover Medical School lecture notes of the 1830s, students didn’t even bother to give the drug its own descriptive page. For many early nineteenth-century doctors, Calomel was the panacea, the “Samson” drug they turned to when all else failed.[5]

The harmful effects of mercury were well-known to early doctors. Along with bloodletting, Calomel was used as a “depletive,” since medical theory held first that inflammation, and later that “excitement of the blood” caused most illness. But early in the nineteenth century, the general public also began to understand the danger of mercurial medicines and to distrust physicians who relied on them. This distrust was fueled by popular critics such as William Cobbett, who said Benjamin Rush’s heroic practices were “one of the great discoveries…which have contributed to the depopulation of the earth.” More testimony against Calomel came from Thomsonian botanical healers, hydropaths and homeopaths who challenged traditional doctors in the early nineteenth century. These “sectarians” took advantage of horror stories that circulated about patients injured or killed by heroic treatment, to erode the social standing of traditional physicians they said were doing more harm than good.[6]

In 1828 the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal (JOURNAL) began offering doctors from New England, New York, and the western territories as far away as New Orleans a forum for sharing cases and a place to read about medical advances. It was active in the ongoing battle against “quackery” and the struggle to establish medicine as a respected profession in America. The editors of the JOURNAL were keenly aware of the public’s distrust of heroic treatment and especially of Calomel. But rather than addressing these concerns open-mindedly, they rejected and even demonized skeptics and dissenters, even when these were fellow doctors relating their cases. The continued use of Calomel and the JOURNAL’s dogged defense of it in the face of mounting evidence from the 1820s to the late 1840s set rural doctors and urban academics in opposing camps. Leading physicians’ obvious lack of consensus on treatments helped undermine the public’s acceptance of the profession.

Examples of this argument abounds in the pages of the JOURNAL. In April 1828, Dr. Finley of Bainbridge Ohio proposed the use of solutions of water and “tartarate of antimony for checking mercurial salivation,” indicating that the problem was already well-known.[7] A September report of a British lecturer’s comment, “To calomel I am averse; on some bowels it acts roughly, and I have seen it apparently occasion miscarriage,” suggests that the use of mercurials was falling out of favor across the Atlantic.[8] In America, doctors had begun reporting cases of “Ptyalism” and “Gangrenopsis.”[9] The effects of Calomel poisoning on patients, and particularly on children, were gruesome. One doctor described a ten-year old girl who had been treated (by another doctor) with eight doses of calomel over the course of three weeks. She suffered from swelling and soreness in her mouth that the other doctor had called canker. This progressed “uninterruptedly to gangrene and sphacelation [morbidity] of both lips, and the greater part of the right cheek, before her death, and left such a hideous spectacle…as made it desirable she might not survive.” In another case, a forty-year-old man “to whom much mercury had been given, and pursued for a considerable time, in small doses, and even after profuse ptyalism had been established…His mouth and face swelled; he could not distinctly articulate for several months; his teeth fell out; and portions of his lower jaw, including the sockets of the teeth, came out. At the end of nine months he died.”[10]

Dr. George Packard of Saco Maine wrote in 1830 about treating “an uncommonly healthy” ten-year old girl for fever. He gave several doses of calomel, and on the second day of treatment, her cheek began to swell. Packard was “confident that the constitutional effect of calomel was not produced, though…a fetor, somewhat resembling that of a mercurial sore mouth, was for some days perceived.” In the fourth week of treatment, the girl’s left cheek became swollen and painful. The doctor tried blisters, poultices, and tonics with no success. The mercurial fetor gave way to a gangrenous stench, and “a large slough came away” from the inside of the girl’s cheek. The “erosion proceeded rapidly,” and the girl began to have regular hemorrhages, which finally killed her in the eighth week of her illness. By this time, the erosion, “commencing at the angle of the mouth, passed by the nose to the upper edge of the malar bone,—thence, by the ear…came anteriorly, including half of the throat and chin.” The girl was unable to eat for much of the two months she suffered from this erosion, and her death, “was for many days heartily desired by her attendants and friends, and, when it came, was not an unwelcome visitor.”[11]

Although it continued to print alarming letters from country doctors describing catastrophic results of Calomel use, the JOURNAL was unwilling to offer an opinion contradicting medical canon. In early 1831 the Editors denounced a “REFORMED Medical College” that had been opened by Dr. John J. Steele in Worthington Ohio. The college’s “chief object of reform,” they said, would be to “dismiss from the material medica, the internal use of mercury, antimony, lead, iron, copper, zinc, arsenic, and other poisonous materials.” The Editors called this “the most weak, absurd and contemptible affair…we ever met with in print.”[12]

In 1834 Dr. Stephen W. Williams of Deerfield, Professor of Medical Jurisprudence at the Berkshire Medical Institution, wrote in defense of mercury. Williams related the case of a ten-year old boy with scarlet fever, to whom he had prescribed calomel. After nine days of treatment, the boy was “attacked with severe haemorrhage from the small arteries of the cheeks and gums, which continued without much intermission for two or three days, and prostrated his strength considerably.” Williams complained, “about this time I was attacked, with the ferocity of a tiger, for administering mercury in this case and destroying the patient…Such is often the gratitude that is awarded to physicians.” Dr. Williams insisted the patient would have died under any other treatment, and proceeded over several pages to cite dozens of medical authorities supporting his use of mercury. His citations went back to the seventeenth century and included advocates of heroic treatment like Benjamin Rush.

Dr. Williams’ article marks a change in the rhetoric surrounding the Calomel argument. Spurred by growing concern over the profession’s declining public image, the Editors of the JOURNAL chose to stand for tradition and the authority of medicine’s canonical texts. “A great change is evidently taking place in regard to the old mode of theorizing,” the Editors complained. “Facts are now first demanded, and every one may then dispose of them according to his own individual fancy.”[13] Country correspondents objected to this “intolerant and overbearing” approach, charging that if any doctors “have the boldness or temerity to doubt their infallibility…they, in the plentitude of their wisdom and power, are determined to inflict summary vengeance on them…by a ten times more frequent and greater use of the article in question, than they otherwise would have done.”[14] But the Editors continued, in columns like their “Remarks on Itinerants,” to declare that “although mercury is “anathematized by quacks and their unconscious dupes, it is a valuable medicine, and could not be dispensed with in general practice.”[15]

The basis of the Editors’ argument for Calomel seems to rest squarely and solely on the authority of tradition. In 1838 the JOURNAL devoted several issues to reprinting a London lecture on the Materia Medica that traced mercury’s use from Pliny and Dioscorides, through the Arabians, to Paracelsus and the alchemists, for whom it was “the summum magnum of all their labors.”[16] In an 1839 conclusion to a “Medical Essay,” on another subject, the Editors attacked “the empiric…[who] is absolutely ignorant of the nature and proper operation of calomel, and therefore in his hands it becomes and edged-tool, which should never be in the hands of the ignorant, the prejudiced, or the insane.”[17] Though the term empiric was widely used as a derogatory catch-all for Thomsonian herbalists, homeopaths, and others, its literal meaning is equally relevant. In the minds of the Editors and their supporters, professional doctors, like contemporary lawyers and ministers, claimed their authority not from experience, but from their knowledge of medicine’s central texts.

The battle raged on, in literally dozens of JOURNAL articles and letters. Most often correspondents and country doctors argued from their observations, while the Editors and their academic experts argued from the texts. At the same time, the JOURNAL and other organs of the medical press bemoaned the doctor’s low social standing relative to ministers and lawyers. One of the first priorities of the American Medical Association (AMA), founded in 1847, was setting minimal standards of education for its members. While this ultimately resulted in the highly empirical, science-based medicine we are familiar with today, at the time it may have functioned (like committees to investigate secret remedies, patent nostrums, and other “quack” cures) more as a reinforcement for authority over experience.[18]

By mid-century the weight of evidence had combined with the establishment of medical schools within elite institutions that had once held them at arms length. Experience was institutionalized as medical science and Calomel faded from use. In his 1850 “Valedictory Address” to the AMA, President John C. Warren remarked “I do remember that at one time most diseases were attacked by mercurials; not only general but local; inflammations and fevers; affections acute and chronic, syphilitic and scrofulous; in short, nearly all diseases, all ages, both sexes, were invaded by this potent mineral.”[19] Warren’s position as Professor of Anatomy at the Harvard Medical School only thirty-seven years after Nathan Smith had arrived at Yale under a cloud of suspicion illustrates how much had changed in a little over a generation. But memory was rapidly fading regarding the divisiveness of the Calomel debate, and the slow and contested evolution of a philosophy of medicine it illustrated. Young doctors were no longer jailed for studying anatomy on stolen corpses. The profession had grown up and experience had won, if not a decisive victory over authority, at least a seat at the table.

Notes:

[1] “A gentleman’s hands are clean,” claimed opponents. Meigs, C. D. (1854). On the nature, signs, and treatment of childbed fevers; in a series of letters addressed to the students of his class. Philadelphia, Blanchard and Lea., Holmes, O. W. (1883). Medical essays, 1842-1882. Boston, Houghton Mifflin.

[2] Massachusetts Medical, S. and S. New England Surgical (1844). "Erisypelas and Puerperal Fever." The Boston medical and surgical journal. XXX(5): 89-95.

[3] Smith, E. A. (1914). The life and letters of Nathan Smith, M.B., M.D. New Haven, Yale University Press; [etc.].

[4] Eberle, J. (1834). Notes of lectures on the theory and practice of medicine, delivered in the Jefferson medical college, at Philadelphia. Cincinnati, Corey & Fairbank.

[5] Cobbett, W. (1885). How to get on in the world, as displayed in the life and writings of William Cobbett. New York, R. Worthington.

[6] Thomson, S. (1822, 1972). A narrative of the life and medical discoveries of Samuel Thomson; containing an account of his system of practice, and the manner of curing disease with vegetable medicine, upon a plan entirely new; to which is added an introduction to his New guide to health, or botanic family physician, containing the principles upon which the system is founded, with remarks on fevers, steaming, poison, &c. New York, Arno Press.

[7] Massachusetts Medical, S. and S. New England Surgical (1828). "Letter." The Boston medical and surgical journal. I(9): 137.

[8] Massachusetts Medical, S. and S. New England Surgical (1828). "Lectures Delivered at Guy's Hospital." The Boston medical and surgical journal. I(29): 458.

[9] Massachusetts Medical, S. and S. New England Surgical (1828). "Letter." The Boston medical and surgical journal. II(43): 679.

[10] Massachusetts Medical, S. and S. New England Surgical (1830). "Some Account of Affections of the Face." The Boston medical and surgical journal. II(48): 758.

[11] Massachusetts Medical, S. and S. New England Surgical (1830). "Letter." The Boston medical and surgical journal. III(21): 337.

[12] Massachusetts Medical, S. and S. New England Surgical (1831). ""REFORMED" Medical College." The Boston medical and surgical journal. IV(6): 101.

[13] Massachusetts Medical, S. and S. New England Surgical (1835). "Self Limited Diseases." The Boston medical and surgical journal. XII(26): 413.

[14] Massachusetts Medical, S. and S. New England Surgical (1835). "Letter." The Boston medical and surgical journal. XII(26): 411.

[15] Massachusetts Medical, S. and S. New England Surgical (1837). "Remarks on Itinerants." The Boston medical and surgical journal. XVI(1): 14.

[16] Massachusetts Medical, S. and S. New England Surgical (1838). "Mercury, from Dr. Sigmond's Lectures on the Materia Medica." The Boston medical and surgical journal. XVIII(9): 133

[17] Massachusetts Medical, S. and S. New England Surgical (1839). "Medical Essay." The Boston medical and surgical journal. XX(6): 94.

[18] Davis, N. S. B. S. W. and ed (1855). History of the American Medical Association from its organization up to January, 1855. Philadelphia, Lippincott, Grambo & Co.

[19] Massachusetts Medical, S. and S. New England Surgical (1850). "Dr. Warren's Valedictory Address." The Boston medical and surgical journal. XLII(20): 409.

I'm glad to have been born a century later!