Boat, Stage, Railroad, Canal (1833)

The steamboat was very large and commodious as all these conveyances are. These steamboats have three stories. The upper one is, as it were, a roofing or terrace on the leads of the second, a very desirable station when the weather is neither too foul nor too fair. A burning sun being, I should think, as little desirable there as a shower of rain. The second floor or deck has the advantage of the ceiling above and yet, the sides being completely open, it is airy and allows free sight of the shores on either hand. Chairs, stools, and benches, are the furniture of these two decks. The one below or third floor downwards in fact, the ground floors being the one near the water, is a spacious room completely roofed and walled in where the passengers take their meals and resort if the weather is unfavorable. At the end of this room is a smaller cabin for the use of the ladies with beds and sofa and all the conveniences necessary if they should like to be sick, whither I came and slept till breakfast time. Vigne's account of the pushing, thrusting, rushing, and devouring on board a western steamboat at mealtimes had prepared me for rather an awful spectacle. But this I find is by no means the case in these more civilized parts and everything was conducted with perfect order, propriety, and civility. The breakfast was good and served and eaten with decency enough. At about half past ten we reached the place where we leave the river to proceed across a part of the State of New Jersey to the Delaware . . . Oh, these coaches! English eye has not seen, English ear has not heard, nor has it entered into the heart of Englishman to conceive the surpassing clumsiness and wretchedness of these leathern inconveniences. They are shaped something like boats, the sides being merely leathern pieces removable at pleasure but which in bad weather are buttoned down to protect the inmates from the wet. There are three seats in this machine, the middle one . . . runs between the carriage doors and lifts away to permit the egress and ingress of the occupants of the other seats . . . For the first few minutes I thought I must have fainted from the intolerable sensation of smothering which I experienced. However, the leathers having been removed and a little more air obtained, I took heart of grace and resigned myself to my fate. Away walloped the four horses, trotting with their front and galloping with their hind legs. And away went we after them, bumping, thumping, jumping, jolting, shaking, tossing and tumbling over the wickedest road I do think, the cruelest, hard-heartedest road that ever wheel rumbled upon. Through bog and marsh, and ruts wider and deeper than any christian ruts I ever saw with the roots of trees protruding across our path, their boughs every now and then giving us an affectionate scratch through the windows. And more than once a half-demolished trunk or stump lying in the middle of the road lifting us up and letting us down again with most awful variations of our poor coach body from its natural position. Bones of me! What a road! Even my father's solid proportions could not keep their level, but were jerked up to the roof and down again every three minutes. Our companions seemed nothing dismayed by these wondrous performances of a coach and four, but laughed and talked incessantly. The young ladies at the very top of their voices and with the national nasal twang . . . The few cottages and farmhouses which we passed reminded me of similar dwellings in France and Ireland, yet the peasantry here have not the same excuse for disorder and dilapidation as either the Irish or French. The farms had the same desolate, untidy, untended look: the gates broken, the fences carelessly put up or ill repaired, the farming utensils sluttishly scattered about a littered yard where the pigs seemed to preside by undisputed right house windows broken and stuffed with paper or clothes, disheveled women and barefooted, anomalous looking human young things. None of the stirring life and activity which such places present in England and Scotland. Above all, none of the enchanting mixture of neatness, order, and rustic elegance and comfort which render so picturesque the surroundings of a farm and the various belongings of agricultural labor in my own dear country. The fences struck me as peculiar, I never saw any such in England. They are made of rails of wood placed horizontally and meeting at obtuse angles, so forming a zig-zag wall of wood which runs over the country like the herringbone seams of a flannel petticoat. At each of the angles, two slanting stakes considerably higher than the rest of the fence were driven into the ground, crossing each other at the top so as to secure the horizontal rails in their position.

At the end of fourteen miles we turned into a swampy field, the whole fourteen coachfuls of us and by the help of heaven bag and baggage were packed into the coaches which stood on the rail-way ready to receive us. The carriages were not drawn by steam like those on the Liverpool rail-way, but by horses, with the mere advantage in speed afforded by the iron ledges which to be sure, compared with our previous progress through the ruts, was considerable. Our coachful got into the first carriage of the train, escaping by way of especial grace, the dust which one's predecessors occasion. This vehicle had but two seats in the usual fashion, each of which held four of us. The whole inside was lined with blazing scarlet leather and the windows shaded with stuff curtains of the same refreshing color which with full complement of passengers on a fine, sunny, American summer's day must make as pretty a little miniature hell as may be, I should think. This railroad is an infinite blessing; 'tis not yet finished but shortly will be so and then the whole of that horrible fourteen miles will be performed in comfort and decency, in less than half the time. In about an hour and a half we reached the end of our rail-road part of the journey and found another steamboat waiting for us, when we all embarked on the Delaware. At about four o'clock we reached Philadelphia, having performed the journey between that and New York (a distance of a hundred miles) in less than ten hours in spite of bogs, ruts, and all other impediments.

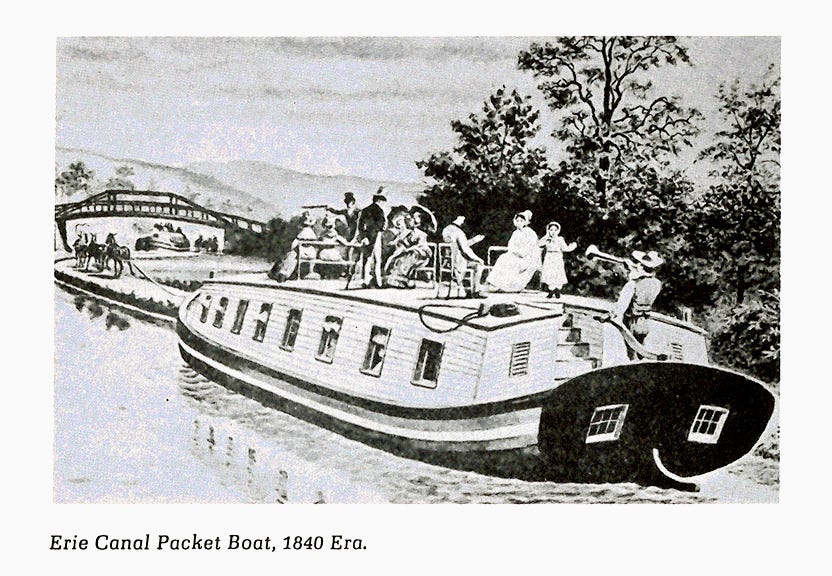

We proceeded by canal to Utica, which distance we performed in a day and a night, starting at two from Schenectady and reaching Utica the next day at about noon. I like travelling by the canal boats very much. Ours was not crowded and the country through which we passed being delightful, the placid moderate gliding through it at about four miles and a half an hour seemed to me infinitely preferable to the noise of wheels, the rumble of a coach, and the jerking of bad roads for the gain of a mile an hour. The only nuisances are the bridges over the canal which are so very low that one is obliged to prostrate oneself on the deck of the boat to avoid being scraped off it, and this humiliation occurs, upon an average, once every quarter of an hour.

The valley of the Mohawk through which we crept the whole sunshining day is beautiful from beginning to end, fertile, soft, rich, and occasionally approaching sublimity and grandeur in its rocks and hanging woods. We had a lovely day and a soft blessed sunset which, just as we came to a point where the canal crosses the river and where the curved and wooded shores on either side recede, leaving a broad smooth basin, threw one of the most exquisite effects of light and color I ever remember to have seen, over the water and through the sky. We sat in the men's cabin until they began making preparations for bed and then withdrew into a room about twelve feet square where a whole tribe of women were getting to their beds. Some half undressed, some brushing, some curling, some washing, some already asleep in their narrow cribs, but all within a quarter of an inch of each other. It made one shudder . . .

At Utica we dined and after dinner I slept profoundly. The gentlemen I believe went out to view the town, which twenty years ago was not, and now is a flourishing place with fine-looking shops, two or three hotels, good broad streets, and a body of lawyers who had a supper at the house where we were staying and kept the night awake with champagne, shouting, toasts, and clapping of hands. So much for the strides of civilization through the savage lands of this new world.

Source: Frances Anne Butler, Journal (1835), I, 128 to II, 186. https://archive.org/details/toldcontemporari03hartrich/page/564/mode/2up