Bacon's Rebellion (1676)

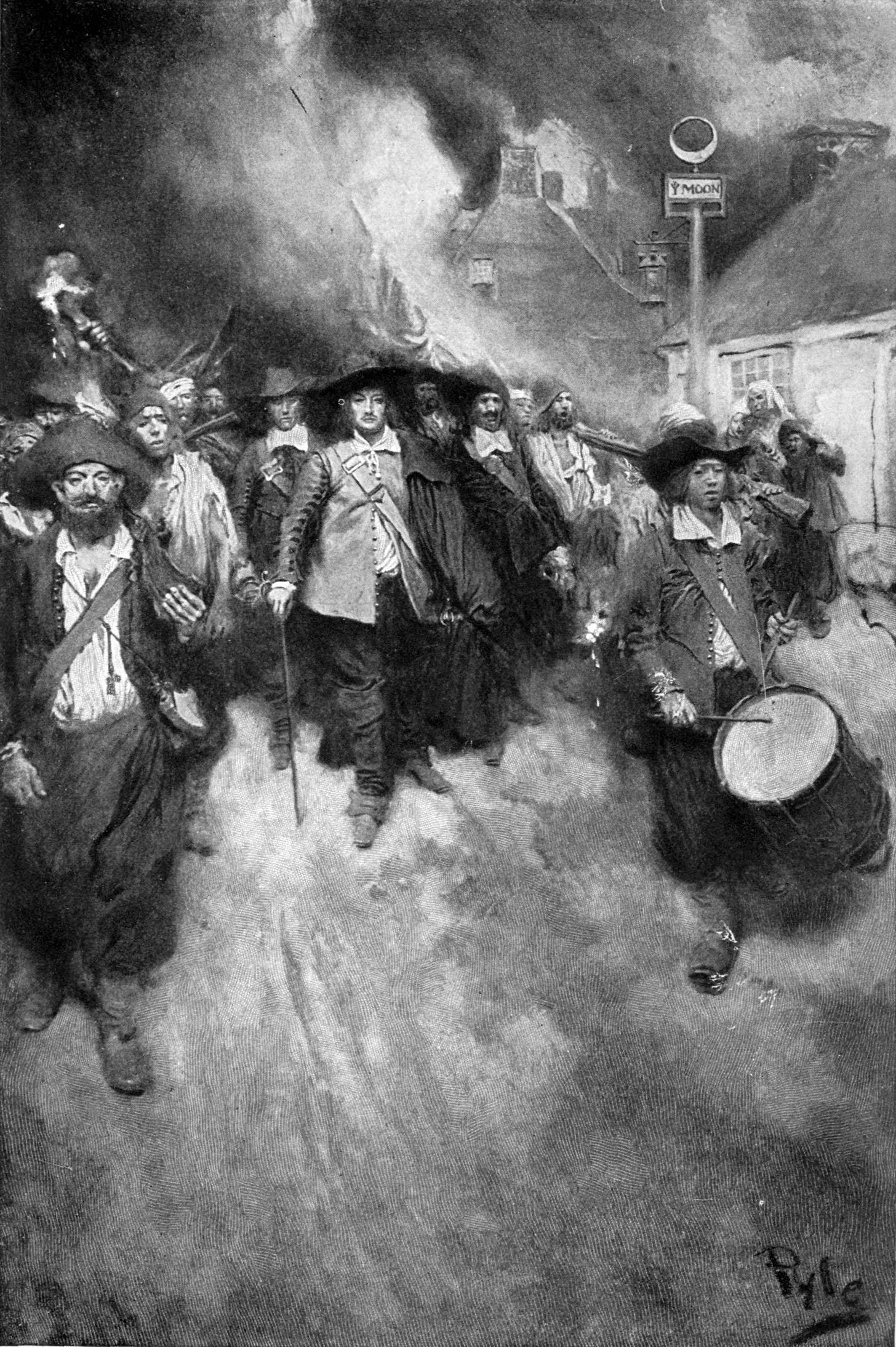

The Burning of Jamestown during Bacon's Rebellion, by Howard Pyle, 1905.

This gentleman who has of late beckoned the attention of all men had the honor to be descended of an ancient and honorable family, his name Nathanael Bacon. To the long-known title of Gentleman, by his long study at the Inns of Court he has since added that of Esquire [he attained a law degree]. His father as he was able so he was willing to allow this his son a very genteel competency [income] to subsist upon, but he as it proved having a soul too large for that allowance, could not contain himself within bounds. Which his careful father perceiving and also that he had a mind to travel consented to his inclination of going to Virginia and accommodated him with a stock for that purpose.

That plantation which he chose to settle in is generally known by the name of Curles situated in the upper part of James River and the time of his revolt was not till the beginning of March, 1676. At which time the Susquo-hannan Indians (a known enemy to that country) having made an insurrection and killed diverse of the English, amongst whom it was his fortune to have a servant slain. In revenge of whose death and other damages he received from those turbulent Susquo-hannians, without the Governor's consent he furiously took up arms against them and was so fortunate as to put them to flight. The aforesaid Governor hearing of his eager pursuit after the vanquished Indians, sent out a select company of soldiers to command him to desist. But he instead of listening thereunto, persisted in his revenge and sent to the Governor to entreat his commission, that he might more cheerfully prosecute his design. Which being denied him by the messenger he sent for that purpose, he notwithstanding continued with his own servants and other English then resident in Curles against them.

In this interim the people of Henrica had returned him Burgess of their county and he came down towards James Town conducted by thirty odd soldiers. The Governor thereupon ordered an alarm to be beaten through the whole town. Bacon thinking himself not secure whilst he remained there within reach of their fort, immediately towed his sloop up the river. Which the Governor perceiving, ordered the ships which lay at Sandy-point to pursue and take him. So that Mr. Bacon finding himself pursued both before and behind, after some capitulations quietly surrendered himself prisoner to the Governor's commissioners. Which action of his was so obliging to the Governor that he granted him his liberty immediately upon parole. And the next day after some private discourse passed betwixt the Governor, the Privy Council, and himself, he was amply restored to all his former honors and dignities, and a commission partly promised him to be General against the Indian army.

But upon farther enquiry it was not thought fit to be granted him; whereat his ambitious mind seemed mightily to be displeased. Insomuch that he gave out that it was his intention to sell his whole concerns in Virginia and to go with his whole family to live either in Merry-land [Maryland] or the South. But this resolution it seems was but a pretense, for afterwards he headed the same runnagado [renegade] English that he formerly found ready to undertake any of his rebellions. And adding to them the assistance of his own slaves and servants, and by the inhabitants informed where some of the Susquohannos were enforted And after he had vanquished them, slew about seventy of them in their fort. Howbeit we may judge what respect he had gained in James Town by this subsequent transaction. When he was first brought here it was frequently reported among the commonalty that he was kept close prisoner, which report caused the people of that town, those of Charles City, Henrico, and New-Kent Counties, being in all about the number of eight hundred or a thousand, to rise and march to his rescue. Whereupon the Governor was forced to desire Mr. Bacon to go himself in person and by his open appearance quiet the people.

Mr. Bacon, dissatisfied that he could not have a commission granted him to go against the Indians, in the night-time departed the town unknown to anybody and about a week after got together between four and five hundred men of New-Kent County with whom he marched to James Town and drew up in order before the House of State. And there peremptorily demanded of the Governor, Council, and Burgesses (there then collected) a commission to go against the Indians. Whereupon to prevent farther danger in so great an exigence, the Council and Burgesses by much entreaty obtained him a commission signed by the Governor. But Bacon was not satisfied with this, but afterwards earnestly importuned and at length obtained an Act of Indemnity to all persons who had sided with him and also letters of recommendations from the Governor to his Majesty in his behalf.

Having obtained these large civilities of the Governor, one would have thought that if the principles of honesty would not have obliged him to peace and loyalty, those of gratitude should. But alas, when men have been once flushed or entered with vice, how hard is it for them to leave it. Especially it tends towards ambition or greatness, which is the general lust of a large soul, the lure of greatness that they have no time left them to consider by what indirect and unlawful means they must (if ever) attain it. This certainly was Mr. Bacon’s crime, who after he had once launched into rebellion and upon submission had been pardoned for it and also restored, as if he had committed no such heinous offense, to his former honor and dignities (which were considerable enough to content any reasonable mind), yet for all this he could not forbear wading into his former misdemeanors and continued his opposition against that prudent and established government ordered by his Majesty of Great Britain to be duly observed in that continent.

In fine [finally], he continued in the woods with a considerable army all last summer and maintained several brushes with the Governor's party. Sometimes routing them and burning all before him, to the great damage of many of his Majesty’s loyal subjects there resident. Sometimes he and his rebels were beaten by the Governor and forced to run for shelter amongst the woods and swamps. In which lamentable condition that unhappy continent has remained for the space of almost a twelve-month, everyone therein that were able being forced to take up arms for security of their own lives and no one reckoning their goods, wives, or children to be their own, since they were so dangerously exposed to the doubtful accidents of an uncertain war.

But the indulgent Heavens, who are alone able to compute what measure of punishments are adequate or fit for the sins or transgressions of a Nation, has in its great mercy thought fit to put a stop at least, if not a total period and conclusion to these Virginian troubles, by the death of this Nat Bacon, the great molestor of the quiet of that miserable nation. So that now we who are here in England and have any relations or correspondence with any of the inhabitants of that continent may by the arrival of the next ships from that coast expect to hear that they are freed from all their dangers, quitted of all their fears, and in great hopes and expectation to live quietly under their own vines and enjoy the benefit of their commendable labors.

I know it is by some reported that this Mr. Bacon was a very hard drinker and that he died by imbibing or taking in too much brandy. But I am informed by those who are persons of undoubted reputation and had the happiness to see the same letter which gave his Majesty an account of his death, that there was no such thing therein mentioned. He was certainly a person imbued with great natural parts which notwithstanding his juvenile extravagances he had adorned with many elaborate acquisitions and by the help of learning and study knew how to manage them to a miracle. It being the general vogue [opinion] of all that knew him, that he usually spoke as much sense in as few words and delivered that sense as opportunely as any they ever kept company with. Wherefore as I am myself a lover of ingenuity though an abhorrer of disturbance or rebellion, I think fit since Providence was pleased to let him die a natural death in his bed, not to asperse him with saying he killed himself with drinking.

Source: Bacon's Rebellion (1676), Anonymous, Strange News from Virginia, etc. (London, 1677), 2-8. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.45493/page/n261/mode/2up