In this one I’m returning to a post I made in July 2020 when I was very new to Substack, so very few people ever saw it. I thought it was interesting when I reread it, so I decided to share it again:

In the process of getting into better physical shape this summer, I’ve been walking a lot. Most of the time, I listen to podcasts or nonfiction audiobooks as I walk. But sometimes I feel like a bit of escapist storytelling and I listen to science fiction. This week I’ve returned to an old favorite, the first novel of Neal Stephenson’s Baroque Cycle, Quicksilver. I guess it would be better called “speculative fiction”, since it takes place between the years 1655 and 1714 and is filled with real and fictional alchemists, natural philosophers, and political leaders of Britain, Europe, and colonial America.

The alchemical characters and early scientists Stephenson mentions in his novel include Newton, Hooke, Leibniz, Huygens, and Boyle – along with others he makes up himself. These people and their settings are depicted in a way that I still find captivating. They were a very big reason why I went to grad school to study history, and when I began studying the peppermint oil industry for my dissertation, I couldn’t help reaching back into the earliest stories of mint. Mint and its uses actually stretch back into early European history, and I enjoyed tracing this story back as far as I could. As also, it turns out, did Albert M. Todd, the final peppermint king in my own story. Todd was a collector of art and old books, and in 1903 he wrote a paper for the American Pharmaceutical Association’s fifty-first annual meeting describing the history of the plant on which his business was based.

Mint, according to Todd, “was among the plants first recognized as of value by the ancients.”[1] It is unclear whether the use of herbs such as mint extends as far into prehistory as the development of staple grains and other food crops, but it is likely that people gathering plants for food and medicinal uses would have been drawn to its pungent leaves. In any case, nearly as soon as people began keeping written records, they wrote about mint. The herb’s family name belonged to a woman of Greek myth, Minthe, turned into a plant by the jealous goddess Persephone after her husband Hades had expressed his interest in her. The medicinal value of the mint plant was first mentioned by Hippocrates in the fifth century BCE. A century later, Aristotle described the plant’s cooling and antiseptic qualities. Theophrastus (371-287 BCE.), Pliny (24-79 CE.), and Galen (129-210 CE.) wrote of mint as an important culinary and medical herb in the ancient world, and Ibn Sina (also known as Avicenna, 980-1037 CE.) carried the tradition forward and helped insure that mint’s uses were not forgotten during Europe’s dark ages.

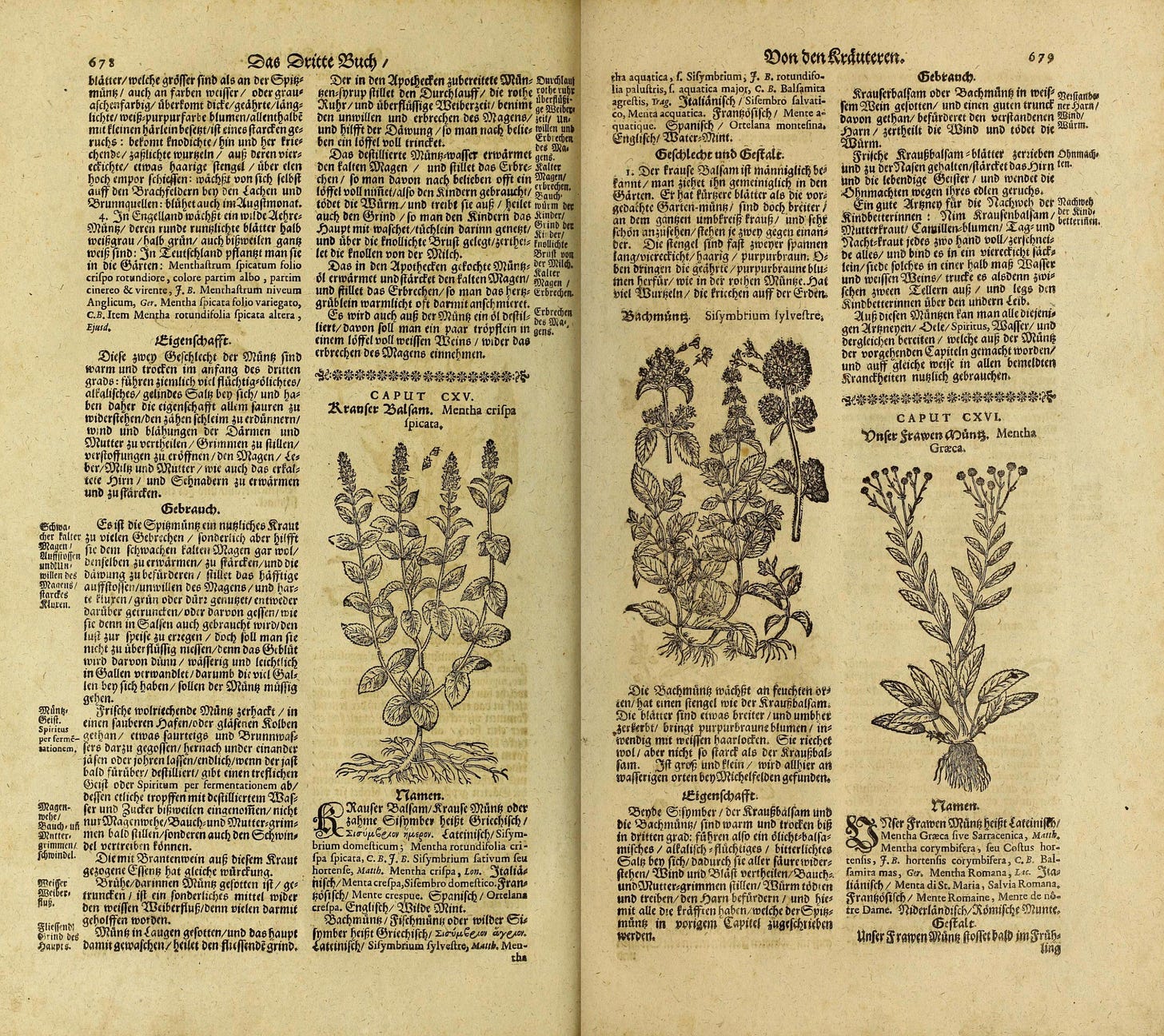

(Hieronymus Brunschwig's Liber de arte Distillandi de Compositis, 1512)

At the beginning of the modern era, the German alchemist Hieronymus Brunschwig (1450-1512) published his Liber de Arte Distillandi de Compositis in Strasbourg. Brunschwig was a surgeon, botanist, and distiller, whose fame was enhanced by the many books he published describing his discoveries. His most famous volume, reprinted over three dozen times between 1537 and 1658, mentioned five species of mints, including Mentha aquatica (Water Mint).[2] The equal space devoted by Brunschwig to the technology of distilling and to the particular herbs he considered valuable highlights the dual character of mint oil. Essential oils are the products of both nature and technology, and the people who grew and distilled them combined traditional agrarian knowledge and technical commercial interests from the start. In addition to being “natural philosophers” or early scientists, alchemists like Brunschwig were also sources of practical information for farmers and millers seeking markets for surplus grain, and for physicians looking for substances to add to their materia medica.

Swiss physician and humanist Theodor Zwinger (1533-1588) was an editor of the early encyclopedia, Theatrum Humanae Vitae, published in five volumes that totaled 4,376 pages. Zwinger’s Theatrum Botanicum, published in 1596, includes nine species of mints and gives their names in a variety of languages including Greek, Latin, Italian, French, Spanish, English, Danish, and Dutch.[3] Zwinger’s ability to collect the wide variety of names suggests both general interest in mints throughout Europe and the extent of the natural habitat of the original plants. Mints of many varieties were common across Europe from time immemorial. Peppermint, however, seems to have originated much more recently in England.

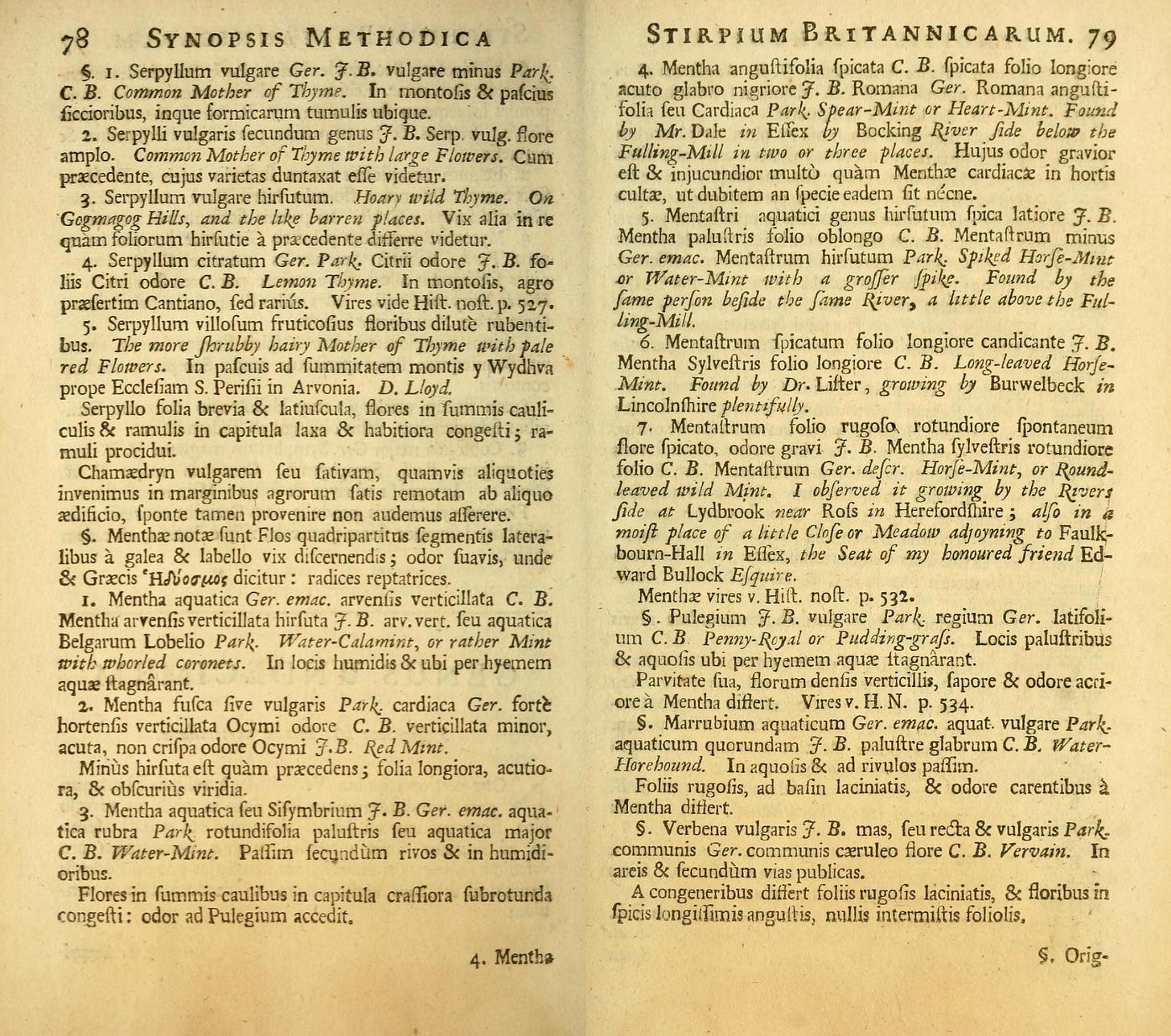

(Mints in Zwinger’s text, 1596)

Like Zwinger’s text, London botanist John Gerarde’s 1597 Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes featured a wide variety of mints including spearmint, which he called Salvia Romana, and two types of water mint.[4] Gerarde’s descriptions and illustrations are very detailed, but the text gives the impression that the author was not writing entirely from personal experience. Some of Gerarde’s descriptions appear to be compilations derived from earlier published works. The tendency of scholars to lean heavily on received tradition began to change in the seventeenth century, when English botanists and their amateur correspondents began to record not only the varieties of plants they observed, but where the specimens could be found. And in these seventeenth-century British herbals, we see the first evidence of peppermint.

In his 1677 Catologus Plantarum Angliae, John Ray (1627-1705) not only described several types of mint in Latin, he remarked—sometimes in English—on where they had been discovered. About a new variety of round-leaved wild mint, Ray said “Rarius occurrit sponte. I observed it growing by the Rivers side at Lydbrook, near Rosse in Hertford-shire, plentifully; and in some places in the West-country, which I do not now remember.”[5] A few years later, in his Synopsis Methodica Stirpium Britannicarum, Ray provided even more detail. He described seven species of mint found in England, including Mentha aquatica (Water-Mint), M. angustifoliaspicata (Spear-Mint), and a new variety (number five in his list) Ray called Mentastri aquatici genus hirsutum spica. Ray further described this plant as “Spiked Horse-Mint or Water-Mint with a grosser spike.” It had been discovered, Ray said, by “Mr. Dale in Essex by Bocking River side…a little above the Fulling-Mill.”[6]

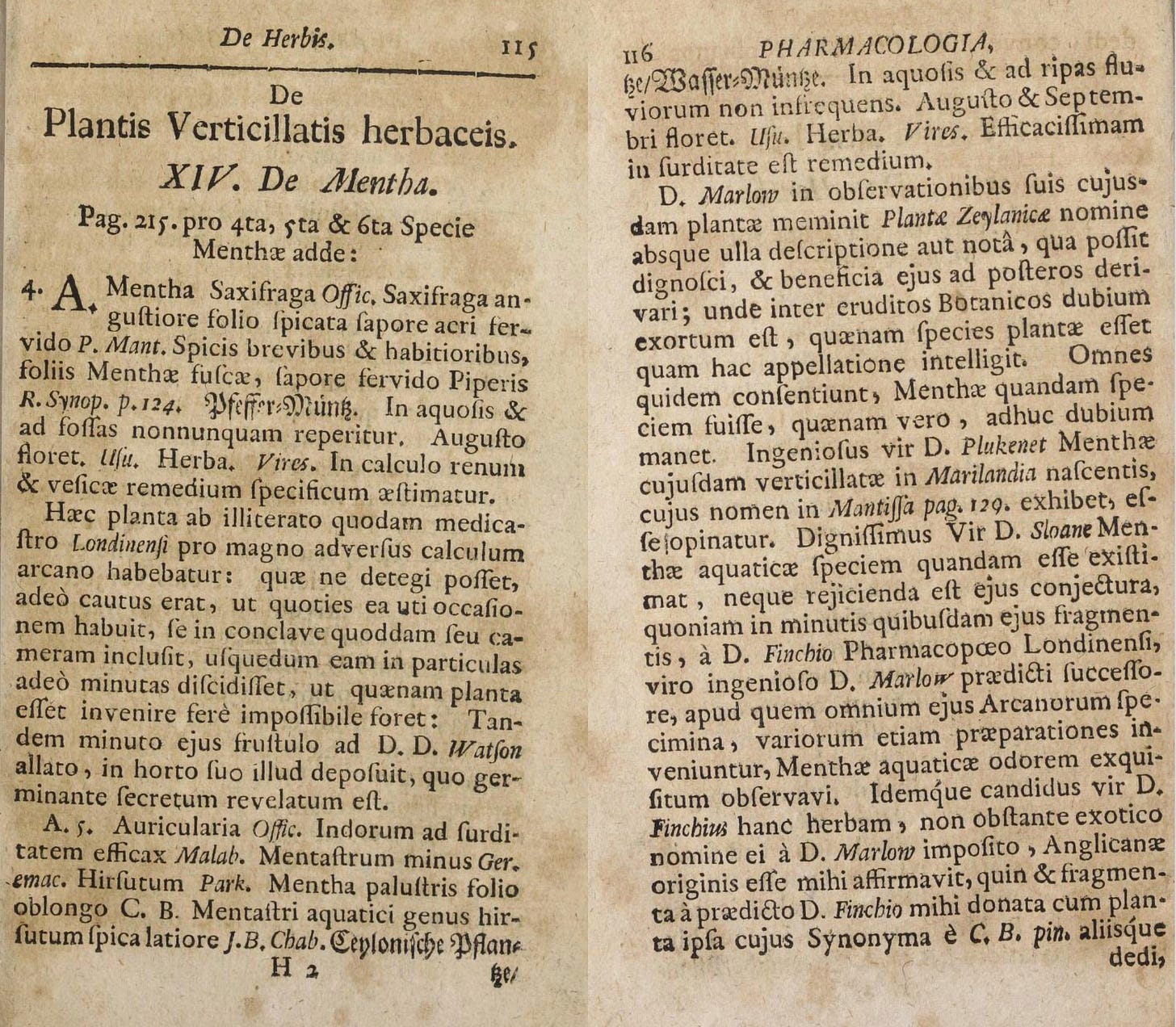

(probably the first mention of peppermint in print, 1690)

John Ray’s 1690 description seems to record the first discovery of peppermint, although Ray didn’t use the name until the second edition of the Synopsis, published in 1696, when he revised the fifth entry on his list to read, “Mentha spicis brevioribus & habitioribus…sapore servido Piperis. Pepper-Mint found by Dr. Eales in Hartfordshire, and communicated to me, since by Mr. Dale in Essex.”[7] Dr. Eales, a botanist from Welwyn, seems to have left no records of his own. But Mr. Dale of Essex did.

Samuel Dale (c. 1659-1739), was a Braintree-based physician and apothecary. He contributed to Ray’s 1690 Synopsis and then published his own Pharmacologia in 1693. Dale mentioned peppermint in his expanded Pharmacologiae Seu Manuductionis ad Materiam Medicam Supplementum, 1705, dubbing the new plant “Mentha Saxifraga…Pepper-Mint.” He said “At times one encounters it in ditches of water” and declared it was effective against kidney and bladder stones.[8]

Acknowledging the immediate commercial value of the newly-discovered peppermint, Dale hinted at why it had taken him a while to recognize the herb in print. “This plant is considered a great secret by some illiterate London doctors,” he said. “When they have occasion to use it, they lock themselves in a room and cut it into particles so minute that it is almost impossible to find out what plant it might be.” Peppermint’s flavor and the perceived medical effectiveness of the new variety was considered so superior that those lucky enough to possess it did everything in their power to hold onto the trade secret. The mystery was solved, Dale said, when “Finally a tiny crumb was carried to Dr. Watson who planted it in his garden where it sprouted and revealed the secret.”[9]

(Samuel Dale’s description of London doctors’ attempts to keep the secret of peppermint, 1705)

Dale’s account is interesting for two reasons. First, it demonstrates that peppermint’s discoverers were well aware that their find was unlike other mints. Because the peppermint plant is a hybrid, it rarely sets seeds and those seeds are not viable. Peppermint plants are effectively sterile. Peppermint must either be discovered where it occurs naturally through a chance crossing of watermint and spearmint, or propagated by cuttings: the “particulas adeo minutus discidisset…ad D.D. Watson allato” mentioned in Dale’s description. Second, the attempt by London physicians to keep peppermint secret illustrates their immediate recognition that the plant’s uniqueness conferred value.

By 1750, peppermint was being commercially cultivated in medicinal herb gardens in and around Mitcham, a suburb of London about nine miles south of the City (now part of greater London). At the end of the eighteenth century a hundred acres of peppermint plants in Mitcham produced three thousand pounds of essential oil annually.[10] The economic impact of peppermint was significant enough that a book review printed in the English Review in 1789 criticized botanist James Adams’s Practical Essays on Agriculture for recommending lavender too enthusiastically. The reviewer noted that “Chamomyle, peppermint, and strawberries, were articles in greater request than lavender, and equally befitting the farmer’s attention.”[11]

As peppermint oil became a popular and valuable product, peppermint began to be sought and found throughout the British countryside. The Botanist’s Guide Through England and Wales (1805) recorded discoveries of M. piperita near the Lea River in Walthamstow, and in other “wet places in…Hertfordshire.” Peppermint was also found “in the running water, in the Village” of Hauxton, outside Cambridge and in the “Town Ditch near Rutland Place, Swansea.”[12] Correspondents wrote of finding peppermint “in rivulets” in Derbyshire and Cheshire, 150 and 200 miles from London. Whether these sightings represented new finds of naturally-occurring hybrids or the discovery of transplants that had escaped from local gardens is unclear. But the sightings do show that peppermint was recognizable and noteworthy when it was found.

Because peppermint plants do not set viable seeds, the species has virtually no genetic diversity. Until experiments with radiation were performed in the 1950s to create a verticillium wilt-resistant commercial cultivar, all the root cuttings used to propagate peppermint were technically the offspring of a very small number of original plants. Plants would slowly change in response to local soils, water, and climate, but the unique identity of peppermint plants meant that unlike other naturally-reproducing species such as spearmint, it was possible to claim a particular plant as the one, true peppermint. And of course, such a designation was extremely valuable to the plant’s owner. This was first achieved in Mitcham, England, with the development of a variety that has been the basis of the entire peppermint oil industry from the 1750s to the present. Peppermint was brought to America from Mitcham several times, as successive peppermint kings returned to acquire root cuttings from the original, authentic peppermint plants to replace plants that had adapted to local conditions. As they made their own pilgrimages to the source of peppermint, growers like Albert Todd were able to discover the interesting history of the plant that made their fortunes. I think I had just as much fun uncovering the story as Todd did, even though it didn’t end up in the final version of the book.

[1] A. M. Todd, "Mint--Its Early History and Modern Commercial Development," Proceedings of the American Pharmaceutical Association at the fifty-first annual meeting (1903), http://catalog.hathitrust.org/api/volumes/oclc/10525073.html. [2] Hieronymus Brunschwig, Liber De Arte Distillandi De Compositis. Das Buch Der Waren Kunst Zu Distillieren Die Composita und Simplicia. 1512). [3] Bernhard Verzasca, Theodor Zwinger, and Pietro Andrea Mattioli, Theatrum Botanicum : Das Ist, Neu Vollkommenes Krüter-Buch : Worinnen Allerhand Erdgewächse Der Bäumen, Stauden Und Kräutern, Welche in Allen Vier Theilen Der Welt, Sonderlich Aber in Europa Herfür Kommen (Basel: Jacob Bertsche, 1596). [4] John Gerarde, The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes (London: Printed by Adam Islip, Joice Norton and Richard Whitakers, 1597). [5] John Ray, Catalogus Plantarum Angliae, Et Insularum Adjacentium Tum Indigenas, Tum in Agris Passim Cultas Complectens in Quo Prêter Synonyma Necessaria, Facultates Quoque Summatim Traduntur, Un Cum Observationibus & Experimentis Novis Medicis & Physicis (Londini: Typis Andr. Clark, Impensis Job. Martyn ... 1677). p. 198. [6] John Ray, Joannis Raii Synopsis Methodica Stirpium Britannicarum: Tum Indigenis, Tum in Agris Cultis Locis Suis Dispositis (Londini: Impensis Gulielmi & Joannis Innys, 1690). p. 79. [7] John Ray, Synopsis Methodica Stirpium Britannicarum in Qua Tum Notae Generum Characteristicae Traduntur, Tum Species Singulae Breviter Describuntur : Ducentae Quinquaginta Plus Minus Novae Species Partim Suis Locis Inferuntur, Partim in Appendice Seorsim Exhibentur : Cum Indice & Virium Epitome (Londini: Prostant apud Sam. Smith ... 1696). p. 124. [8] Samuel Dale, Samuelis Dale Pharmacologiae Seu Manuductionis Ad Materiam Medicam Supplementum: ... Cum Duplici Indice (Londini: Impensis Sam. Smith, & Benj. Walford, 1705). [9] Ibid. p. 126. [10] James E. Landing, American Essence; a History of the Peppermint and Spearmint Industry in the United States (Kalamazoo: Mich., 1969). p. 6. [11] "Art. Iv. Practical Essays on Agriculture; Containing an Account of Soils, and the Manner of Correcting Them," English review, or, An abstract of English and foreign literature, 1783-1795 14 (Sep 1789 1789). [12] Dawson Turner and L. W. Dillwyn, "The Botanist's Guide through England and Wales," (1805), http://catalog.hathitrust.org/api/volumes/oclc/6526315.html.

Fascinating! Your book on the peppermint kings sent me down many research trails, and I often wanted you to include *more* stories--and this is one of them. I wanted to know more about Albert Todd's "Menta" farm, the history of peddlers and their place in the economy, etc. Thanks!