Adolf Augustus Berle, Jr. (1895-1971) was apparently the youngest graduate of Harvard Law School at age 21, after Louis Brandeis. Berle was a member of Franklin Roosevelt’s “Brain Trust”, an Assistant Secretary of State for Latin American Affairs, and later Ambassador to Brazil. Along with Harvard economist Gardiner C. Means, he wrote a foundational study of corporate governance in 1932, The Modern Corporation and Private Property. I’ll be reviewing that book soon, but today I’ve been reading a shorter and later volume by Berle alone, called The 20th Century Capitalist Revolution. I read this as background for my fall 2020 course on the Gilded Age and resistance, to see how people’s thinking about these issues changed over time.

Berle introduced the subject in the 1954 volume by saying the modern corporation had become the “major agency by which the economic life of the United States is carried on” (6) and corporate businesses have become “essentially revolutionary instruments in twentieth-century capitalism” (17). But economic theory had not kept up with changes in business organization, he said. Berle described history as “among other things, the record of groupings of human beings” and said he wanted to explore “property and its relation to power” (21). The corporation emerged in the twentieth century as one of the main “institutions which organize power” (22) through the process of “collectivizing capital” (23). But the concentration of capital and power Berle saw in the modern corporation made it look more to him like a political than like an economic actor.

Berle cited a 1953 study finding that “135 corporations own 45 per cent of the industrial assets of the United States” (25). Although he said the trend toward monopoly seemed to have diminished, Berle called the condition in which “a few large corporations dominate” each industry a “concentrate” (26). Most of the economy and “more than half of all American industry—and that the most important half—is operated by ‘concentrates’”, Berle said, with the largest 200 corporations owning more than half the economy outright (27). But the major industrial corporations controled an even larger part of the economy through agency contracts (like car dealerships) and supply relationships (gas stations) where the corporation makes most of the important decisions of even nominally independent small businesses. As a result, the “mid-twentieth-century American capitalist system depends on and revolves around the operations of a relatively few very large corporations” in industries “concentrated in the hands of extremely few corporate units” (28).

Ironically, this is not altogether different from socialism, where Berle said “all productive property is held or ‘owned’ by the agencies of the socialist state” (31). Like states, he said, large corporations require a “unified and concentrated system of organization and command.” What he was really getting at, which I find very interesting, is exploring power. “We know little about power,” he said (32). So we ought to examine the similarities and differences between how it works in governments vs. large businesses. “Mid-twentieth-century capitalism has been given the power and the means of more or less planned economy,” Berle said (35). If the corporations are guiding our national industrial policy, we should better understand how they make decisions. This is where Berle believed the theories of classical economics break down. The “judgment of the marketplace” doesn’t really control large corporations because the only people whose opinions matter are the investor class, which is “relatively narrow” and whose opinions in any case “frequently differ from broad public opinion swings of the kind evidenced in national or even local elections” (36). A broader, more representative public opinion, Berle said, might be more effective in placing a check on business decision-making because the public could conceivably limit the capital funds available to corporations who didn’t toe the line. But the desires of the people who provide the most capital are so predictable and in line with corporate plans that they’re rarely an impediment.

Berle went on to say that in 1953 economists at National City Bank did a study of the $150 billion spent by corporations between 1946 and 1953 on capital improvements (mostly plant and equipment upgrades). They found that about two thirds (or $99 billion) of those funds came from “internal sources” such as retained earnings and cash reserves. Another $25 billion was financed with current bank borrowing. About an eighth of the money ($18 billion) was raised through bond issues, but Berle said this money wasn’t really subject to “market-place judgment” because at least half of it consisted of private placements or institutional bond sales. Only $9 billion, or about one sixteenth of the $150 billion capital, was raised through sale of stock, and of that amount only about $5 billion through sale of common stock. In other words, of the $150 billion corporations spent on capital improvements in the post-war decade, only about a thirtieth was subjected to the risk-assessment and goal-approval process that we normally understood to be a feature of managerial decision-making and corporate governance (37-8).

Berle contended that this was the “real pattern of twentieth-century capitalism” and I think this deserves a much closer study (39). The entrepreneurial capitalist was becoming a thing of the past, said Berle. “In his place stand the boards of directors of corporations, chiefly large ones,” and although he didn’t mention it, chiefly interlocking boards sharing members. So basically, a very narrow elite of corporate managers. In this way, “one of the classic checks on corporate power has been weakened” (40). The resulting corporate power was by no means absolute: Berle suggested it was limited “vertically” by competition between the few large firms dominating each industry and “horizontally” by competition from substitute products in (often emerging) other industries. But this concentration of power is significant, he said, and probably growing. Berle suggested that much less is known about the actual concentration of power than is revealed in data about concentration of asset ownership by corporations.

Discussing the new form of competition between a few dominant firms in these concentrated industries, Berle claimed it “leads more often to political than to economic resolution of events” (48). Although he didn’t quite say that these corporations collude, he did suggest the end result looks a lot like “an industrial plan controlling the industry.” And the government had a big hand in this “planned industry” economy: banks are coordinated by the Federal Reserve, transportation by the Interstate Commerce Act, utilities by the Federal Power Commission, communications by the FCC, etc. (49). Berle recognized that this was not that different from what other societies call socialism, and he mentioned that economists like Friedrich Hayek (the link between Austrian Economics and the Chicago School) “considers this trend a plain step on the road to serfdom” (The Road to Serfdom was Hayek’s famous book on the topic. 50). He observed that this “socialism” has been advocated by both American parties and concluded:

The rude fact appears to be that when 45 per cent of American industry is dominated by 135 corporations which necessarily must administer their prices, no one else is going to risk the logical results of wholly free competition. (50-1)

Competition, if it existed at all, “operates within far narrower limits than classical economics contemplated” (51). But no one really wants competition, Berle said; “they all want, not a perpetual struggle, but a steady job”, and the labor unions agree. Instead of market competition, America has planning, “and planning does not reduce power but increases it” (52). Berle concluded the chapter by arguing that so far, corporations had kept themselves in check and behaved pretty well. Public opinion could be effective, he claimed, and there was “considerable public apprehension” about not only government power but “of undue concentration of power anywhere” (57). So far, though, corporations had been producing things people needed and wanted at reasonable process, and had been responsive to consumer demand (although Berle admitted businesses could manipulate demand, citing the tobacco industry as an example). “The real guarantee of nonstatist industrial organization in America,” he said, “is a substantially satisfied public” (59). But there was no denying that “the corporation is now, essentially, a nonstatist political institution, and its directors are in the same boat with public office-holders” (60). America, Berle observed in 1954, was beginning to be governed not by representatives of the people, but by corporate managers. He didn’t think it was a problem at the time — in fact, he suggested that in many cases experts might be better decision-makers than “market judgment”. But he made some assumptions about the benevolence of these new, unelected political leaders based on observations at the time. If those assumptions no longer hold, then we may be in uncharted waters.

I think this is a useful source as I’m thinking about my Gilded Age course, so I’ll return with notes on the next chapter soon.

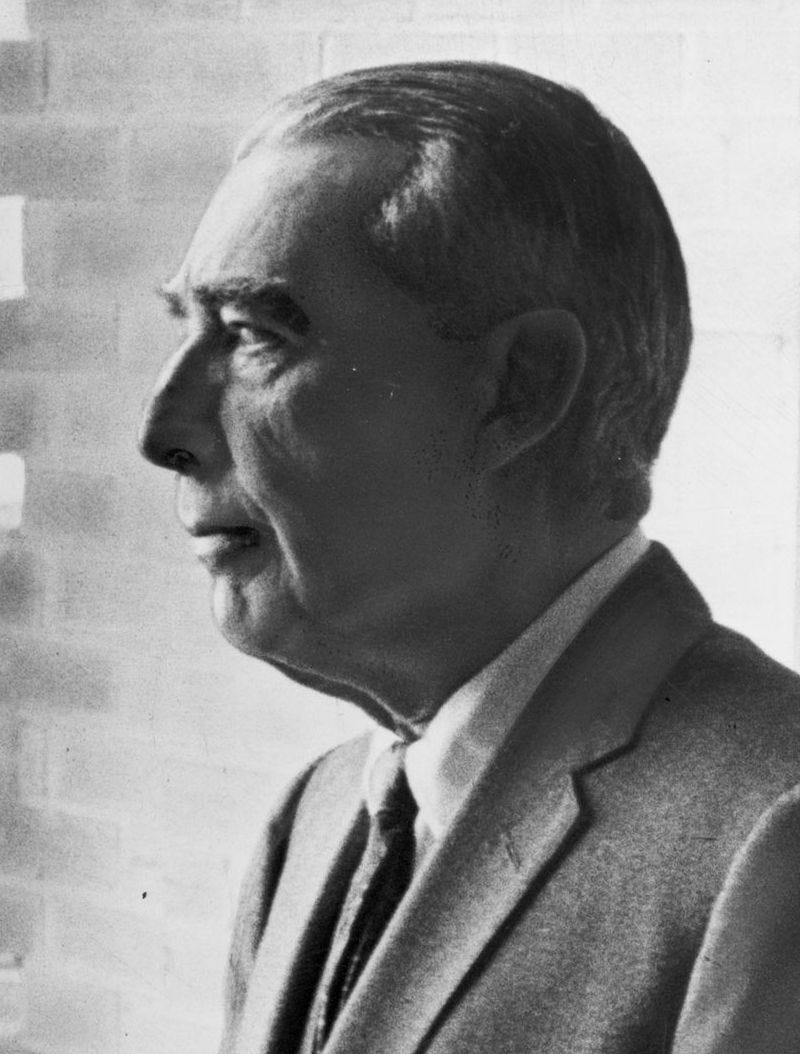

(image: Berle in 1965, photo by Walter Albertin, public domain)