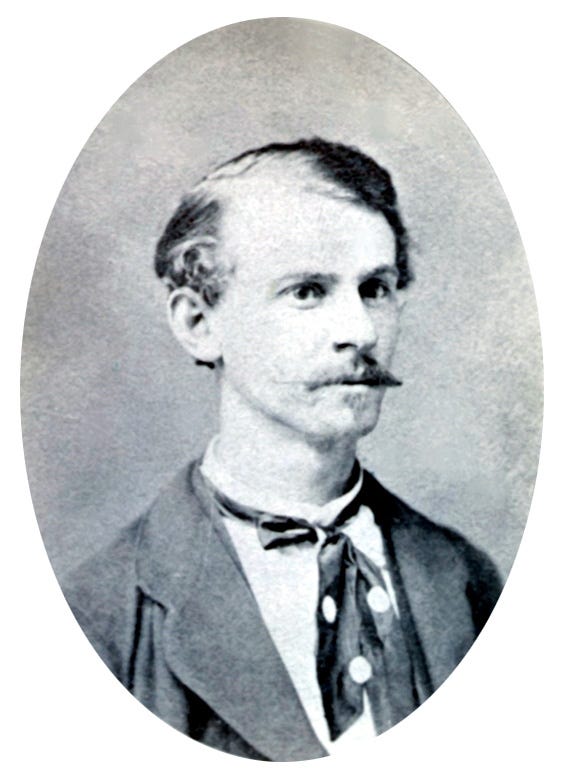

A Bit More on Albert Parsons

(1848-1887) American-born socialist and anarchist newspaper editor and activist. Parsons grew up in Texas and was at first sympathetic with the Confederacy but after the Civil War embraced the cause of Reconstruction. In the mid-1870s, Parsons became interested in socialism and was one of the leading English-speaking members of the Social-Democratic Party in 1875. In 1876 he joined the Knights of Labor and by 1877 was one of the founders of the Chicago local, along with his friend George Schilling. During the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 he was again asked (as one of the few socialists in Chicago fluent in English) to speak. After addressing a crowd of 30,000 on July 21, 1877, he lost his job as a typesetter with the Chicago Times. He went to the offices of the Chicagoer Arbeiter-Zeitung and was arrested there and threatened by some of Chicago's leaders in the presence of the police chief.

Although he was familiar with Marxism, Parsons was more aligned with Anarchism. He became active in the 8-hour movement and when the national leadership of the Knights of Labor declined to support the movement he led a parade, with his wife Lucy and their two children, of 80,000 workers down Michigan Avenue on May Day 1886. A national strike ensued, with about 350,000 workers at 1,200 factories walking out.

On May 3rd strikers and strikebreakers faced off at the McCormick reaper factory in Chicago. Managers called the police, who arrived and opened fire on the strikers, killing six. Labor leaders announced a protest for the following evening at Haymarket Square. Parsons attended, as did the Mayor of Chicago, who noticed it was a peaceful gathering. As it was wrapping up (after Parsons had left), police arrived and ordered the crowd to disperse. A bomb was thrown from the crowd toward the police, killing one. The police opened fire on the crowd, killing six more men and wounding many more, including many of the police.

Albert Parsons left Chicago and went to Waukesha Wisconsin for several weeks. When most of his friends were arrested and charged with capital crimes, Parsons returned to Chicago and turned himself in, at the courtroom where the trial was being held. Eight men were tried and although there was no evidence linking them to the bomb (and eyewitness testimony that none had thrown it) they were convicted as scapegoats. Five, including Parsons, were sentenced to death. Albert Parsons wrote a letter to readers of his paper, The Alarm, from death row, saying:

And now to all I say: Falter not. Lay bare the inequities of capitalism; expose the slavery of law; proclaim the tyranny of government; denounce the greed, cruelty, abominations of the privileged class who riot and revel on the labor of their wage-slaves.

Parsons was hanged at age 39 on November 11th, 1887. His wife, Lucy, published Albert's autobiography and several more books about him. She went on to be one of the founders of the Industrial Workers of the World in 1905 and edited radical newspapers for most of her life. Lucy Parsons died in 1942.

Accessible sources about Albert R. Parsons:

https://archive.org/details/LaborAgitator/page/n11/mode/2up

https://archive.org/details/anarchismitsphil00parsrich/page/n3/mode/2up

https://archive.org/details/lifeofalbertrpar00pars/page/n7/mode/2up

https://famous-trials.com/haymarket/1170-parsonsautobiography